GitHub’s one-dimensional view of open source contributions

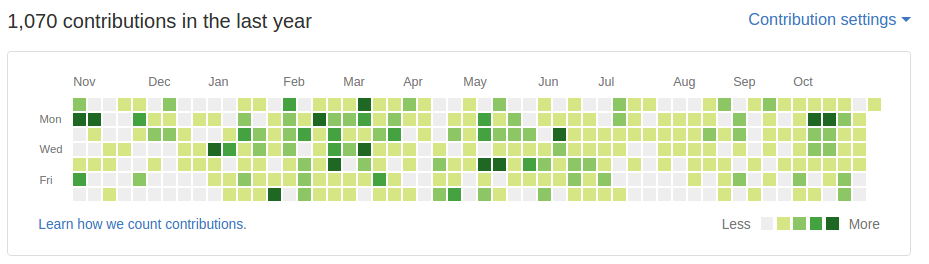

TL;DR One of the most harmful parts of the GitHub platform is the code contribution calendar. This “hacker score card” overemphasizes the value of commits over the other kinds of important contributions to open source projects, like doing code reviews and discussing bugs and new features on the issue tracker.

A skewed view of reality

We love it and we hate it: the GitHub contribution calendar.

Some of the common grievances against the calendar, until very recently, were:

It only showed 1 year worth of prior work. There are projects on GitHub with 10 or even 20 years of contribution history. So if GitHub is going to be part of your resume, you need to be able to see your entire life’s work.

It only showed public contributions. Now you can also show activity from private repositories.

I personally found this last item a bit annoying, because it implicitly reinforces the bias against talented software engineers who choose to spend their time supporting their families through paid work rather than spending extracurricular time doing unpaid open source work. Having a respectable GitHub pedigree is only one way to get a feel for someone’s value as an engineer.

For me, the worst part of the contribution calendar is that it only shows commits / pull requests and issue creation. If you’ve been involved in a large open source project, the idea that writing code is the only valuable way to contribute is a bit silly. In the pandas project for example, the core team spends significantly more time on such matters as:

Code review and merging pull requests (pandas has had over 5000 pull requests, and rarely has fewer than 100 open at any given time).

Development roadmapping and design discussions.

Categorizing and prioritizing a sprawling issue tracker, which can have hundreds or thousands of open issues. These categorizations also help new contributors find issues to work on to get involved in the project (see “Difficulty: Low” issues in pandas).

Working with issue reporters to create bug reproductions or to help understand new features or requirements.

In fact, I would credit a great deal of pandas’s success to the fact that we have such engaged, responsive, and empathic core developers. I can confirm, for example, that Jeff Reback is a real person with a day job and a family rather than a sophisticated AI watching the pandas GitHub issues 24/7/365. It’s not uncommon to get feedback on pull requests and have bug fixes merged within 24-72 hours of reporting. This is incredibly important to making users feel comfortable with relying on a piece of software like pandas in production.

Improving the score card

It seems a bit cynical to suggest that some people might only contribute to an open source project if it helps them with their “GitHub High Score”. You currently get points on your profile for commits, but not reviewing code or participating in discussions on the issue tracker. I would really like to see this change.

As an aside, one of the things I like about the Apache Software Foundation’s semi-formalized development culture is that becoming a committer or PMC member of a project requires you to do more than simply write patches. You earn social “karma” through code review, e-mail and JIRA discussions, user community engagement, and so forth.