13 Data Analysis Examples

Now that we've reached the final chapter of this book, we're going to take a look at a number of real-world datasets. For each dataset, we'll use the techniques presented in this book to extract meaning from the raw data. The demonstrated techniques can be applied to all manner of other datasets. This chapter contains a collection of miscellaneous example datasets that you can use for practice with the tools in this book.

The example datasets are found in the book's accompanying GitHub repository. If you are unable to access GitHub, you can also get them from the repository mirror on Gitee.

13.1 Bitly Data from 1.USA.gov

In 2011, the URL shortening service Bitly partnered with the US government website USA.gov to provide a feed of anonymous data gathered from users who shorten links ending with .gov or .mil. In 2011, a live feed as well as hourly snapshots were available as downloadable text files. This service is shut down at the time of this writing (2022), but we preserved one of the data files for the book's examples.

In the case of the hourly snapshots, each line in each file contains a common form of web data known as JSON, which stands for JavaScript Object Notation. For example, if we read just the first line of a file, we may see something like this:

In [5]: path = "datasets/bitly_usagov/example.txt"

In [6]: with open(path) as f:

...: print(f.readline())

...:

{ "a": "Mozilla\\/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit\\/535.11

(KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome\\/17.0.963.78 Safari\\/535.11", "c": "US", "nk": 1,

"tz": "America\\/New_York", "gr": "MA", "g": "A6qOVH", "h": "wfLQtf", "l":

"orofrog", "al": "en-US,en;q=0.8", "hh": "1.usa.gov", "r":

"http:\\/\\/www.facebook.com\\/l\\/7AQEFzjSi\\/1.usa.gov\\/wfLQtf", "u":

"http:\\/\\/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov\\/pubmed\\/22415991", "t": 1331923247, "hc":

1331822918, "cy": "Danvers", "ll": [ 42.576698, -70.954903 ] }Python has both built-in and third-party libraries for converting a JSON string into a Python dictionary. Here we’ll use the json module and its loads function invoked on each line in the sample file we downloaded:

import json

with open(path) as f:

records = [json.loads(line) for line in f]The resulting object records is now a list of Python dictionaries:

In [18]: records[0]

Out[18]:

{'a': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64) AppleWebKit/535.11 (KHTML, like Gecko)

Chrome/17.0.963.78 Safari/535.11',

'al': 'en-US,en;q=0.8',

'c': 'US',

'cy': 'Danvers',

'g': 'A6qOVH',

'gr': 'MA',

'h': 'wfLQtf',

'hc': 1331822918,

'hh': '1.usa.gov',

'l': 'orofrog',

'll': [42.576698, -70.954903],

'nk': 1,

'r': 'http://www.facebook.com/l/7AQEFzjSi/1.usa.gov/wfLQtf',

't': 1331923247,

'tz': 'America/New_York',

'u': 'http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22415991'}Counting Time Zones in Pure Python

Suppose we were interested in finding the time zones that occur most often in the dataset (the tz field). There are many ways we could do this. First, let’s extract a list of time zones again using a list comprehension:

In [15]: time_zones = [rec["tz"] for rec in records]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-15-abdeba901c13> in <module>

----> 1 time_zones = [rec["tz"] for rec in records]

<ipython-input-15-abdeba901c13> in <listcomp>(.0)

----> 1 time_zones = [rec["tz"] for rec in records]

KeyError: 'tz'Oops! Turns out that not all of the records have a time zone field. We can handle this by adding the check if "tz" in rec at the end of the list comprehension:

In [16]: time_zones = [rec["tz"] for rec in records if "tz" in rec]

In [17]: time_zones[:10]

Out[17]:

['America/New_York',

'America/Denver',

'America/New_York',

'America/Sao_Paulo',

'America/New_York',

'America/New_York',

'Europe/Warsaw',

'',

'',

'']Just looking at the first 10 time zones, we see that some of them are unknown (empty string). You can filter these out also, but I’ll leave them in for now. Next, to produce counts by time zone, I’ll show two approaches: a harder way (using just the Python standard library) and a simpler way (using pandas). One way to do the counting is to use a dictionary to store counts while we iterate through the time zones:

def get_counts(sequence):

counts = {}

for x in sequence:

if x in counts:

counts[x] += 1

else:

counts[x] = 1

return countsUsing more advanced tools in the Python standard library, you can write the same thing more briefly:

from collections import defaultdict

def get_counts2(sequence):

counts = defaultdict(int) # values will initialize to 0

for x in sequence:

counts[x] += 1

return countsI put this logic in a function just to make it more reusable. To use it on the time zones, just pass the time_zones list:

In [20]: counts = get_counts(time_zones)

In [21]: counts["America/New_York"]

Out[21]: 1251

In [22]: len(time_zones)

Out[22]: 3440If we wanted the top 10 time zones and their counts, we can make a list of tuples by (count, timezone) and sort it:

def top_counts(count_dict, n=10):

value_key_pairs = [(count, tz) for tz, count in count_dict.items()]

value_key_pairs.sort()

return value_key_pairs[-n:]We have then:

In [24]: top_counts(counts)

Out[24]:

[(33, 'America/Sao_Paulo'),

(35, 'Europe/Madrid'),

(36, 'Pacific/Honolulu'),

(37, 'Asia/Tokyo'),

(74, 'Europe/London'),

(191, 'America/Denver'),

(382, 'America/Los_Angeles'),

(400, 'America/Chicago'),

(521, ''),

(1251, 'America/New_York')]If you search the Python standard library, you may find the collections.Counter class, which makes this task even simpler:

In [25]: from collections import Counter

In [26]: counts = Counter(time_zones)

In [27]: counts.most_common(10)

Out[27]:

[('America/New_York', 1251),

('', 521),

('America/Chicago', 400),

('America/Los_Angeles', 382),

('America/Denver', 191),

('Europe/London', 74),

('Asia/Tokyo', 37),

('Pacific/Honolulu', 36),

('Europe/Madrid', 35),

('America/Sao_Paulo', 33)]Counting Time Zones with pandas

You can create a DataFrame from the original set of records by passing the list of records to pandas.DataFrame:

In [28]: frame = pd.DataFrame(records)We can look at some basic information about this new DataFrame, such as column names, inferred column types, or number of missing values, using frame.info():

In [29]: frame.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 3560 entries, 0 to 3559

Data columns (total 18 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 a 3440 non-null object

1 c 2919 non-null object

2 nk 3440 non-null float64

3 tz 3440 non-null object

4 gr 2919 non-null object

5 g 3440 non-null object

6 h 3440 non-null object

7 l 3440 non-null object

8 al 3094 non-null object

9 hh 3440 non-null object

10 r 3440 non-null object

11 u 3440 non-null object

12 t 3440 non-null float64

13 hc 3440 non-null float64

14 cy 2919 non-null object

15 ll 2919 non-null object

16 _heartbeat_ 120 non-null float64

17 kw 93 non-null object

dtypes: float64(4), object(14)

memory usage: 500.8+ KB

In [30]: frame["tz"].head()

Out[30]:

0 America/New_York

1 America/Denver

2 America/New_York

3 America/Sao_Paulo

4 America/New_York

Name: tz, dtype: objectThe output shown for the frame is the summary view, shown for large DataFrame objects. We can then use the value_counts method for the Series:

In [31]: tz_counts = frame["tz"].value_counts()

In [32]: tz_counts.head()

Out[32]:

tz

America/New_York 1251

521

America/Chicago 400

America/Los_Angeles 382

America/Denver 191

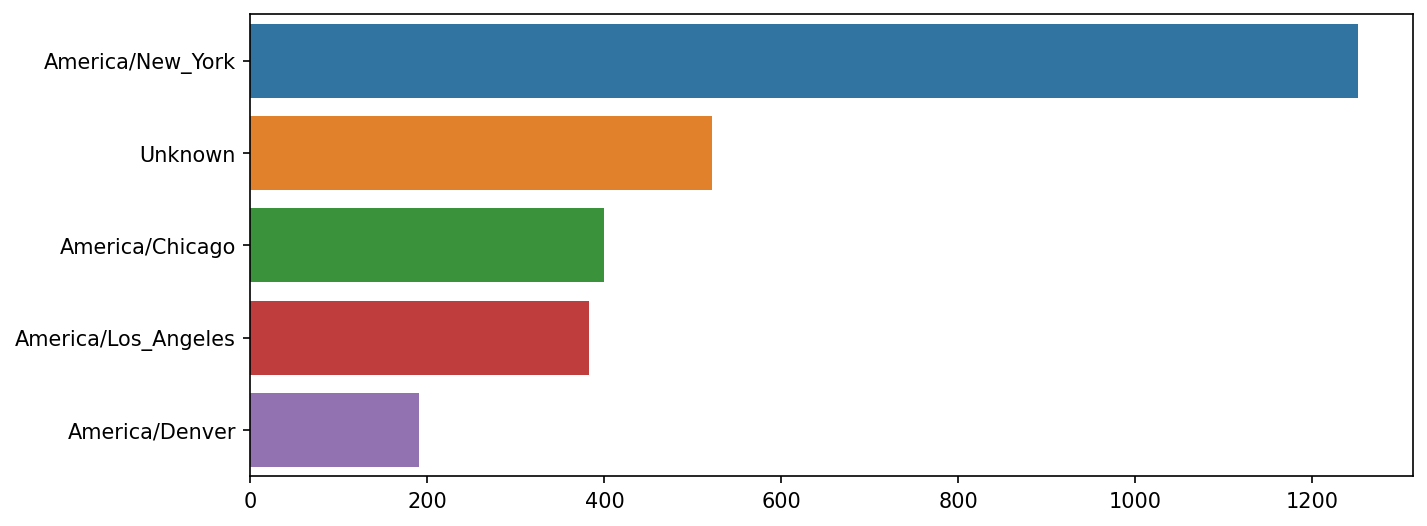

Name: count, dtype: int64We can visualize this data using matplotlib. We can make the plots a bit nicer by filling in a substitute value for unknown or missing time zone data in the records. We replace the missing values with the fillna method and use Boolean array indexing for the empty strings:

In [33]: clean_tz = frame["tz"].fillna("Missing")

In [34]: clean_tz[clean_tz == ""] = "Unknown"

In [35]: tz_counts = clean_tz.value_counts()

In [36]: tz_counts.head()

Out[36]:

tz

America/New_York 1251

Unknown 521

America/Chicago 400

America/Los_Angeles 382

America/Denver 191

Name: count, dtype: int64At this point, we can use the seaborn package to make a horizontal bar plot (see Top time zones in the 1.usa.gov sample data for the resulting visualization):

In [38]: import seaborn as sns

In [39]: subset = tz_counts.head()

In [40]: sns.barplot(y=subset.index, x=subset.to_numpy())

The a field contains information about the browser, device, or application used to perform the URL shortening:

In [41]: frame["a"][1]

Out[41]: 'GoogleMaps/RochesterNY'

In [42]: frame["a"][50]

Out[42]: 'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 5.1; rv:10.0.2) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/10.0.2'

In [43]: frame["a"][51][:50] # long line

Out[43]: 'Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; U; Android 2.2.2; en-us; LG-P9'Parsing all of the interesting information in these “agent” strings may seem like a daunting task. One possible strategy is to split off the first token in the string (corresponding roughly to the browser capability) and make another summary of the user behavior:

In [44]: results = pd.Series([x.split()[0] for x in frame["a"].dropna()])

In [45]: results.head(5)

Out[45]:

0 Mozilla/5.0

1 GoogleMaps/RochesterNY

2 Mozilla/4.0

3 Mozilla/5.0

4 Mozilla/5.0

dtype: object

In [46]: results.value_counts().head(8)

Out[46]:

Mozilla/5.0 2594

Mozilla/4.0 601

GoogleMaps/RochesterNY 121

Opera/9.80 34

TEST_INTERNET_AGENT 24

GoogleProducer 21

Mozilla/6.0 5

BlackBerry8520/5.0.0.681 4

Name: count, dtype: int64Now, suppose you wanted to decompose the top time zones into Windows and non-Windows users. As a simplification, let’s say that a user is on Windows if the string "Windows" is in the agent string. Since some of the agents are missing, we’ll exclude these from the data:

In [47]: cframe = frame[frame["a"].notna()].copy()We want to then compute a value for whether or not each row is Windows:

In [48]: cframe["os"] = np.where(cframe["a"].str.contains("Windows"),

....: "Windows", "Not Windows")

In [49]: cframe["os"].head(5)

Out[49]:

0 Windows

1 Not Windows

2 Windows

3 Not Windows

4 Windows

Name: os, dtype: objectThen, you can group the data by its time zone column and this new list of operating systems:

In [50]: by_tz_os = cframe.groupby(["tz", "os"])The group counts, analogous to the value_counts function, can be computed with size. This result is then reshaped into a table with unstack:

In [51]: agg_counts = by_tz_os.size().unstack().fillna(0)

In [52]: agg_counts.head()

Out[52]:

os Not Windows Windows

tz

245.0 276.0

Africa/Cairo 0.0 3.0

Africa/Casablanca 0.0 1.0

Africa/Ceuta 0.0 2.0

Africa/Johannesburg 0.0 1.0Finally, let’s select the top overall time zones. To do so, I construct an indirect index array from the row counts in agg_counts. After computing the row counts with agg_counts.sum("columns"), I can call argsort() to obtain an index array that can be used to sort in ascending order:

In [53]: indexer = agg_counts.sum("columns").argsort()

In [54]: indexer.values[:10]

Out[54]: array([24, 20, 21, 92, 87, 53, 54, 57, 26, 55])I use take to select the rows in that order, then slice off the last 10 rows (largest values):

In [55]: count_subset = agg_counts.take(indexer[-10:])

In [56]: count_subset

Out[56]:

os Not Windows Windows

tz

America/Sao_Paulo 13.0 20.0

Europe/Madrid 16.0 19.0

Pacific/Honolulu 0.0 36.0

Asia/Tokyo 2.0 35.0

Europe/London 43.0 31.0

America/Denver 132.0 59.0

America/Los_Angeles 130.0 252.0

America/Chicago 115.0 285.0

245.0 276.0

America/New_York 339.0 912.0pandas has a convenience method called nlargest that does the same thing:

In [57]: agg_counts.sum(axis="columns").nlargest(10)

Out[57]:

tz

America/New_York 1251.0

521.0

America/Chicago 400.0

America/Los_Angeles 382.0

America/Denver 191.0

Europe/London 74.0

Asia/Tokyo 37.0

Pacific/Honolulu 36.0

Europe/Madrid 35.0

America/Sao_Paulo 33.0

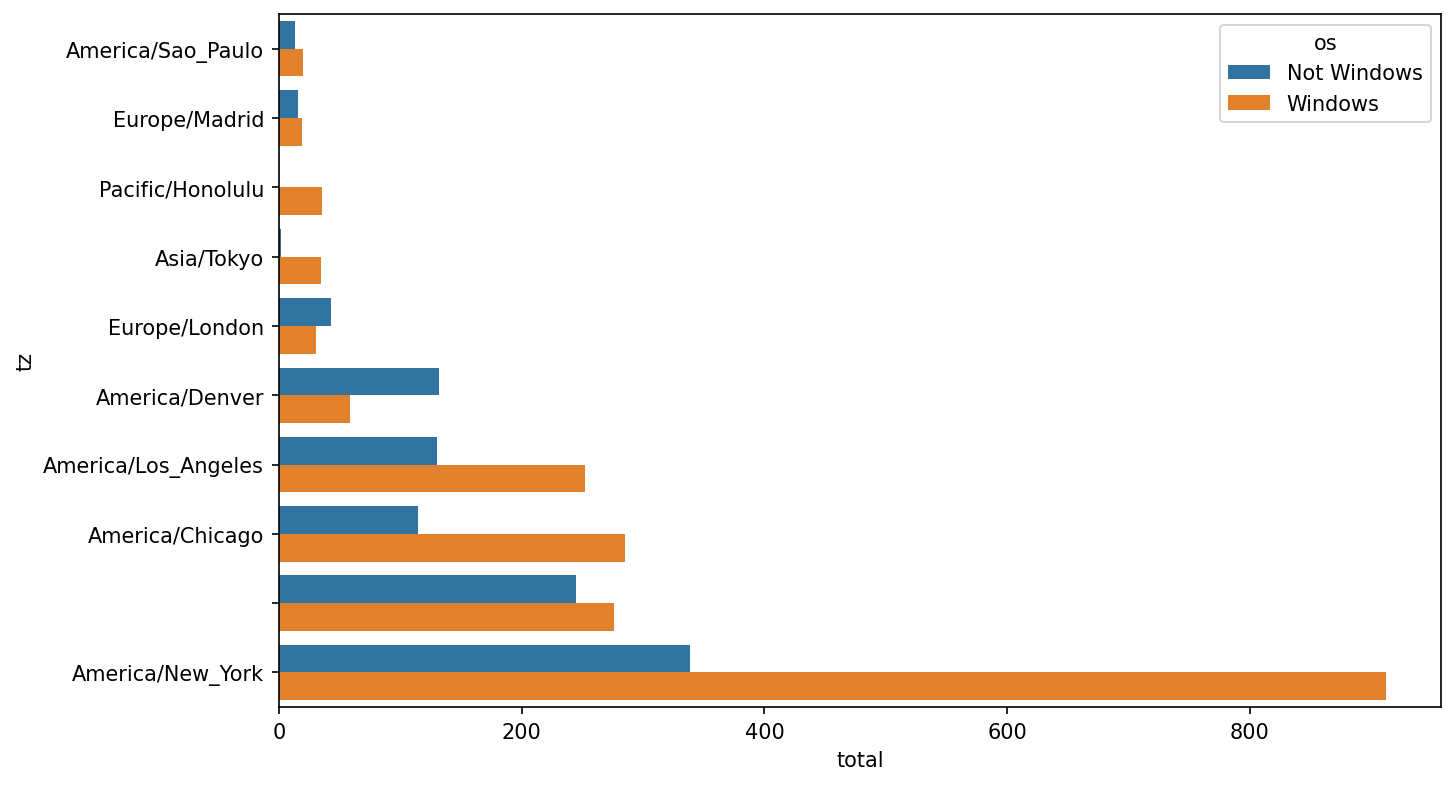

dtype: float64Then, this can be plotted in a grouped bar plot comparing the number of Windows and non-Windows users, using seaborn's barplot function (see Top time zones by Windows and non-Windows users). I first call count_subset.stack() and reset the index to rearrange the data for better compatibility with seaborn:

In [59]: count_subset = count_subset.stack()

In [60]: count_subset.name = "total"

In [61]: count_subset = count_subset.reset_index()

In [62]: count_subset.head(10)

Out[62]:

tz os total

0 America/Sao_Paulo Not Windows 13.0

1 America/Sao_Paulo Windows 20.0

2 Europe/Madrid Not Windows 16.0

3 Europe/Madrid Windows 19.0

4 Pacific/Honolulu Not Windows 0.0

5 Pacific/Honolulu Windows 36.0

6 Asia/Tokyo Not Windows 2.0

7 Asia/Tokyo Windows 35.0

8 Europe/London Not Windows 43.0

9 Europe/London Windows 31.0

In [63]: sns.barplot(x="total", y="tz", hue="os", data=count_subset)

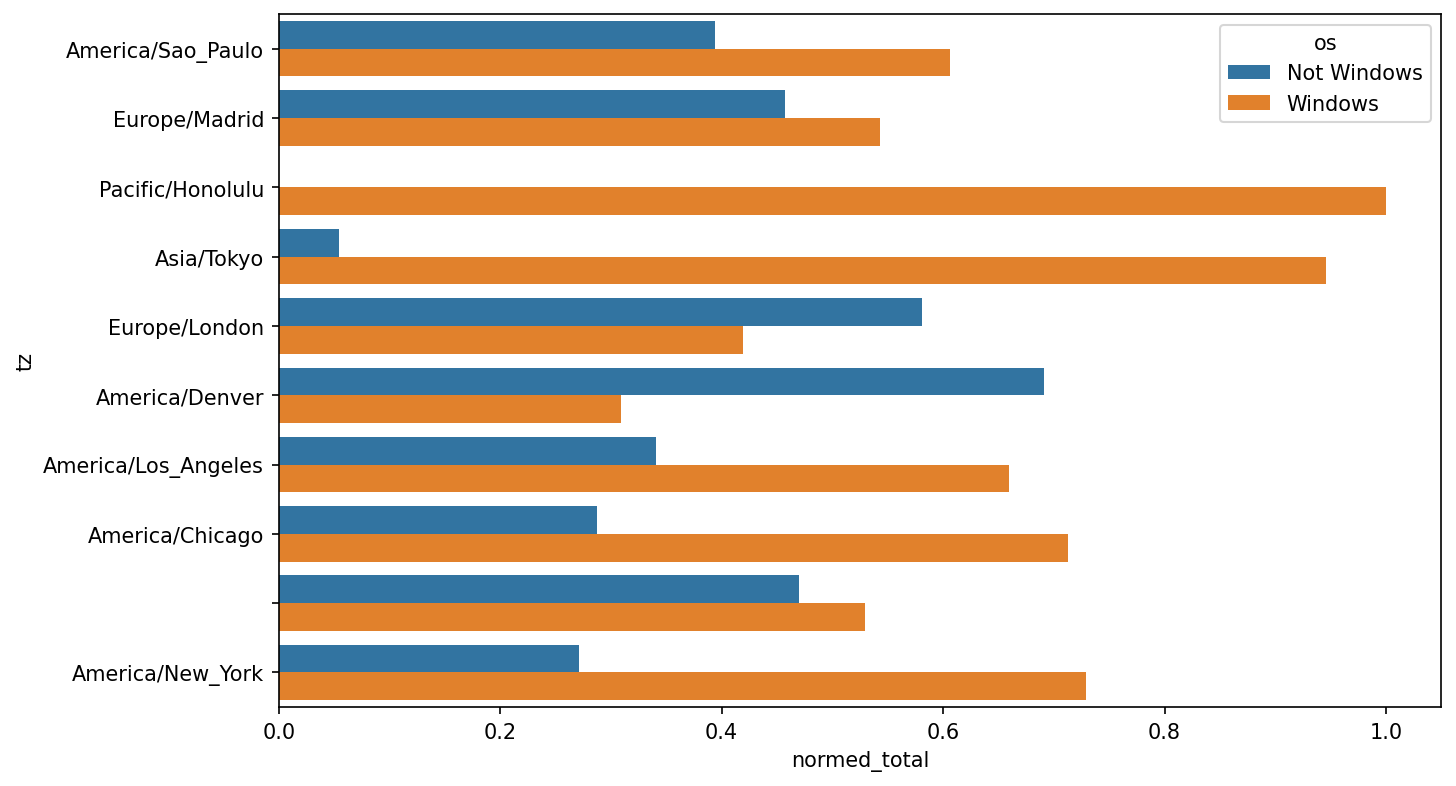

It is a bit difficult to see the relative percentage of Windows users in the smaller groups, so let's normalize the group percentages to sum to 1:

def norm_total(group):

group["normed_total"] = group["total"] / group["total"].sum()

return group

results = count_subset.groupby("tz").apply(norm_total)Then plot this in Percentage Windows and non-Windows users in top occurring time zones:

In [66]: sns.barplot(x="normed_total", y="tz", hue="os", data=results)

We could have computed the normalized sum more efficiently by using the transform method with groupby:

In [67]: g = count_subset.groupby("tz")

In [68]: results2 = count_subset["total"] / g["total"].transform("sum")13.2 MovieLens 1M Dataset

GroupLens Research provides a number of collections of movie ratings data collected from users of MovieLens in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The data provides movie ratings, movie metadata (genres and year), and demographic data about the users (age, zip code, gender identification, and occupation). Such data is often of interest in the development of recommendation systems based on machine learning algorithms. While we do not explore machine learning techniques in detail in this book, I will show you how to slice and dice datasets like these into the exact form you need.

The MovieLens 1M dataset contains one million ratings collected from six thousand users on four thousand movies. It’s spread across three tables: ratings, user information, and movie information. We can load each table into a pandas DataFrame object using pandas.read_table. Run the following code in a Jupyter cell:

unames = ["user_id", "gender", "age", "occupation", "zip"]

users = pd.read_table("datasets/movielens/users.dat", sep="::",

header=None, names=unames, engine="python")

rnames = ["user_id", "movie_id", "rating", "timestamp"]

ratings = pd.read_table("datasets/movielens/ratings.dat", sep="::",

header=None, names=rnames, engine="python")

mnames = ["movie_id", "title", "genres"]

movies = pd.read_table("datasets/movielens/movies.dat", sep="::",

header=None, names=mnames, engine="python")You can verify that everything succeeded by looking at each DataFrame:

In [70]: users.head(5)

Out[70]:

user_id gender age occupation zip

0 1 F 1 10 48067

1 2 M 56 16 70072

2 3 M 25 15 55117

3 4 M 45 7 02460

4 5 M 25 20 55455

In [71]: ratings.head(5)

Out[71]:

user_id movie_id rating timestamp

0 1 1193 5 978300760

1 1 661 3 978302109

2 1 914 3 978301968

3 1 3408 4 978300275

4 1 2355 5 978824291

In [72]: movies.head(5)

Out[72]:

movie_id title genres

0 1 Toy Story (1995) Animation|Children's|Comedy

1 2 Jumanji (1995) Adventure|Children's|Fantasy

2 3 Grumpier Old Men (1995) Comedy|Romance

3 4 Waiting to Exhale (1995) Comedy|Drama

4 5 Father of the Bride Part II (1995) Comedy

In [73]: ratings

Out[73]:

user_id movie_id rating timestamp

0 1 1193 5 978300760

1 1 661 3 978302109

2 1 914 3 978301968

3 1 3408 4 978300275

4 1 2355 5 978824291

... ... ... ... ...

1000204 6040 1091 1 956716541

1000205 6040 1094 5 956704887

1000206 6040 562 5 956704746

1000207 6040 1096 4 956715648

1000208 6040 1097 4 956715569

[1000209 rows x 4 columns]Note that ages and occupations are coded as integers indicating groups described in the dataset’s README file. Analyzing the data spread across three tables is not a simple task; for example, suppose you wanted to compute mean ratings for a particular movie by gender identity and age. As you will see, this is more convenient to do with all of the data merged together into a single table. Using pandas’s merge function, we first merge ratings with users and then merge that result with the movies data. pandas infers which columns to use as the merge (or join) keys based on overlapping names:

In [74]: data = pd.merge(pd.merge(ratings, users), movies)

In [75]: data

Out[75]:

user_id movie_id rating timestamp gender age occupation zip

0 1 1193 5 978300760 F 1 10 48067 \

1 2 1193 5 978298413 M 56 16 70072

2 12 1193 4 978220179 M 25 12 32793

3 15 1193 4 978199279 M 25 7 22903

4 17 1193 5 978158471 M 50 1 95350

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

1000204 5949 2198 5 958846401 M 18 17 47901

1000205 5675 2703 3 976029116 M 35 14 30030

1000206 5780 2845 1 958153068 M 18 17 92886

1000207 5851 3607 5 957756608 F 18 20 55410

1000208 5938 2909 4 957273353 M 25 1 35401

title genres

0 One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) Drama

1 One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) Drama

2 One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) Drama

3 One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) Drama

4 One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) Drama

... ... ...

1000204 Modulations (1998) Documentary

1000205 Broken Vessels (1998) Drama

1000206 White Boys (1999) Drama

1000207 One Little Indian (1973) Comedy|Drama|Western

1000208 Five Wives, Three Secretaries and Me (1998) Documentary

[1000209 rows x 10 columns]

In [76]: data.iloc[0]

Out[76]:

user_id 1

movie_id 1193

rating 5

timestamp 978300760

gender F

age 1

occupation 10

zip 48067

title One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975)

genres Drama

Name: 0, dtype: objectTo get mean movie ratings for each film grouped by gender, we can use the pivot_table method:

In [77]: mean_ratings = data.pivot_table("rating", index="title",

....: columns="gender", aggfunc="mean")

In [78]: mean_ratings.head(5)

Out[78]:

gender F M

title

$1,000,000 Duck (1971) 3.375000 2.761905

'Night Mother (1986) 3.388889 3.352941

'Til There Was You (1997) 2.675676 2.733333

'burbs, The (1989) 2.793478 2.962085

...And Justice for All (1979) 3.828571 3.689024This produced another DataFrame containing mean ratings with movie titles as row labels (the "index") and gender as column labels. I first filter down to movies that received at least 250 ratings (an arbitrary number); to do this, I group the data by title, and use size() to get a Series of group sizes for each title:

In [79]: ratings_by_title = data.groupby("title").size()

In [80]: ratings_by_title.head()

Out[80]:

title

$1,000,000 Duck (1971) 37

'Night Mother (1986) 70

'Til There Was You (1997) 52

'burbs, The (1989) 303

...And Justice for All (1979) 199

dtype: int64

In [81]: active_titles = ratings_by_title.index[ratings_by_title >= 250]

In [82]: active_titles

Out[82]:

Index([''burbs, The (1989)', '10 Things I Hate About You (1999)',

'101 Dalmatians (1961)', '101 Dalmatians (1996)', '12 Angry Men (1957)',

'13th Warrior, The (1999)', '2 Days in the Valley (1996)',

'20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954)', '2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)',

'2010 (1984)',

...

'X-Men (2000)', 'Year of Living Dangerously (1982)',

'Yellow Submarine (1968)', 'You've Got Mail (1998)',

'Young Frankenstein (1974)', 'Young Guns (1988)',

'Young Guns II (1990)', 'Young Sherlock Holmes (1985)',

'Zero Effect (1998)', 'eXistenZ (1999)'],

dtype='object', name='title', length=1216)The index of titles receiving at least 250 ratings can then be used to select rows from mean_ratings using .loc:

In [83]: mean_ratings = mean_ratings.loc[active_titles]

In [84]: mean_ratings

Out[84]:

gender F M

title

'burbs, The (1989) 2.793478 2.962085

10 Things I Hate About You (1999) 3.646552 3.311966

101 Dalmatians (1961) 3.791444 3.500000

101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.240000 2.911215

12 Angry Men (1957) 4.184397 4.328421

... ... ...

Young Guns (1988) 3.371795 3.425620

Young Guns II (1990) 2.934783 2.904025

Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) 3.514706 3.363344

Zero Effect (1998) 3.864407 3.723140

eXistenZ (1999) 3.098592 3.289086

[1216 rows x 2 columns]To see the top films among female viewers, we can sort by the F column in descending order:

In [86]: top_female_ratings = mean_ratings.sort_values("F", ascending=False)

In [87]: top_female_ratings.head()

Out[87]:

gender F M

title

Close Shave, A (1995) 4.644444 4.473795

Wrong Trousers, The (1993) 4.588235 4.478261

Sunset Blvd. (a.k.a. Sunset Boulevard) (1950) 4.572650 4.464589

Wallace & Gromit: The Best of Aardman Animation (1996) 4.563107 4.385075

Schindler's List (1993) 4.562602 4.491415Measuring Rating Disagreement

Suppose you wanted to find the movies that are most divisive between male and female viewers. One way is to add a column to mean_ratings containing the difference in means, then sort by that:

In [88]: mean_ratings["diff"] = mean_ratings["M"] - mean_ratings["F"]Sorting by "diff" yields the movies with the greatest rating difference so that we can see which ones were preferred by women:

In [89]: sorted_by_diff = mean_ratings.sort_values("diff")

In [90]: sorted_by_diff.head()

Out[90]:

gender F M diff

title

Dirty Dancing (1987) 3.790378 2.959596 -0.830782

Jumpin' Jack Flash (1986) 3.254717 2.578358 -0.676359

Grease (1978) 3.975265 3.367041 -0.608224

Little Women (1994) 3.870588 3.321739 -0.548849

Steel Magnolias (1989) 3.901734 3.365957 -0.535777Reversing the order of the rows and again slicing off the top 10 rows, we get the movies preferred by men that women didn’t rate as highly:

In [91]: sorted_by_diff[::-1].head()

Out[91]:

gender F M diff

title

Good, The Bad and The Ugly, The (1966) 3.494949 4.221300 0.726351

Kentucky Fried Movie, The (1977) 2.878788 3.555147 0.676359

Dumb & Dumber (1994) 2.697987 3.336595 0.638608

Longest Day, The (1962) 3.411765 4.031447 0.619682

Cable Guy, The (1996) 2.250000 2.863787 0.613787Suppose instead you wanted the movies that elicited the most disagreement among viewers, independent of gender identification. Disagreement can be measured by the variance or standard deviation of the ratings. To get this, we first compute the rating standard deviation by title and then filter down to the active titles:

In [92]: rating_std_by_title = data.groupby("title")["rating"].std()

In [93]: rating_std_by_title = rating_std_by_title.loc[active_titles]

In [94]: rating_std_by_title.head()

Out[94]:

title

'burbs, The (1989) 1.107760

10 Things I Hate About You (1999) 0.989815

101 Dalmatians (1961) 0.982103

101 Dalmatians (1996) 1.098717

12 Angry Men (1957) 0.812731

Name: rating, dtype: float64Then, we sort in descending order and select the first 10 rows, which are roughly the 10 most divisively rated movies:

In [95]: rating_std_by_title.sort_values(ascending=False)[:10]

Out[95]:

title

Dumb & Dumber (1994) 1.321333

Blair Witch Project, The (1999) 1.316368

Natural Born Killers (1994) 1.307198

Tank Girl (1995) 1.277695

Rocky Horror Picture Show, The (1975) 1.260177

Eyes Wide Shut (1999) 1.259624

Evita (1996) 1.253631

Billy Madison (1995) 1.249970

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) 1.246408

Bicentennial Man (1999) 1.245533

Name: rating, dtype: float64You may have noticed that movie genres are given as a pipe-separated (|) string, since a single movie can belong to multiple genres. To help us group the ratings data by genre, we can use the explode method on DataFrame. Let's take a look at how this works. First, we can split the genres string into a list of genres using the str.split method on the Series:

In [96]: movies["genres"].head()

Out[96]:

0 Animation|Children's|Comedy

1 Adventure|Children's|Fantasy

2 Comedy|Romance

3 Comedy|Drama

4 Comedy

Name: genres, dtype: object

In [97]: movies["genres"].head().str.split("|")

Out[97]:

0 [Animation, Children's, Comedy]

1 [Adventure, Children's, Fantasy]

2 [Comedy, Romance]

3 [Comedy, Drama]

4 [Comedy]

Name: genres, dtype: object

In [98]: movies["genre"] = movies.pop("genres").str.split("|")

In [99]: movies.head()

Out[99]:

movie_id title

0 1 Toy Story (1995) \

1 2 Jumanji (1995)

2 3 Grumpier Old Men (1995)

3 4 Waiting to Exhale (1995)

4 5 Father of the Bride Part II (1995)

genre

0 [Animation, Children's, Comedy]

1 [Adventure, Children's, Fantasy]

2 [Comedy, Romance]

3 [Comedy, Drama]

4 [Comedy] Now, calling movies.explode("genre") generates a new DataFrame with one row for each "inner" element in each list of movie genres. For example, if a movie is classified as both a comedy and a romance, then there will be two rows in the result, one with just "Comedy" and the other with just "Romance":

In [100]: movies_exploded = movies.explode("genre")

In [101]: movies_exploded[:10]

Out[101]:

movie_id title genre

0 1 Toy Story (1995) Animation

0 1 Toy Story (1995) Children's

0 1 Toy Story (1995) Comedy

1 2 Jumanji (1995) Adventure

1 2 Jumanji (1995) Children's

1 2 Jumanji (1995) Fantasy

2 3 Grumpier Old Men (1995) Comedy

2 3 Grumpier Old Men (1995) Romance

3 4 Waiting to Exhale (1995) Comedy

3 4 Waiting to Exhale (1995) DramaNow, we can merge all three tables together and group by genre:

In [102]: ratings_with_genre = pd.merge(pd.merge(movies_exploded, ratings), users

)

In [103]: ratings_with_genre.iloc[0]

Out[103]:

movie_id 1

title Toy Story (1995)

genre Animation

user_id 1

rating 5

timestamp 978824268

gender F

age 1

occupation 10

zip 48067

Name: 0, dtype: object

In [104]: genre_ratings = (ratings_with_genre.groupby(["genre", "age"])

.....: ["rating"].mean()

.....: .unstack("age"))

In [105]: genre_ratings[:10]

Out[105]:

age 1 18 25 35 45 50

genre

Action 3.506385 3.447097 3.453358 3.538107 3.528543 3.611333 \

Adventure 3.449975 3.408525 3.443163 3.515291 3.528963 3.628163

Animation 3.476113 3.624014 3.701228 3.740545 3.734856 3.780020

Children's 3.241642 3.294257 3.426873 3.518423 3.527593 3.556555

Comedy 3.497491 3.460417 3.490385 3.561984 3.591789 3.646868

Crime 3.710170 3.668054 3.680321 3.733736 3.750661 3.810688

Documentary 3.730769 3.865865 3.946690 3.953747 3.966521 3.908108

Drama 3.794735 3.721930 3.726428 3.782512 3.784356 3.878415

Fantasy 3.317647 3.353778 3.452484 3.482301 3.532468 3.581570

Film-Noir 4.145455 3.997368 4.058725 4.064910 4.105376 4.175401

age 56

genre

Action 3.610709

Adventure 3.649064

Animation 3.756233

Children's 3.621822

Comedy 3.650949

Crime 3.832549

Documentary 3.961538

Drama 3.933465

Fantasy 3.532700

Film-Noir 4.125932 13.3 US Baby Names 1880–2010

The United States Social Security Administration (SSA) has made available data on the frequency of baby names from 1880 through the present. Hadley Wickham, an author of several popular R packages, has this dataset in illustrating data manipulation in R.

We need to do some data wrangling to load this dataset, but once we do that we will have a DataFrame that looks like this:

In [4]: names.head(10)

Out[4]:

name sex births year

0 Mary F 7065 1880

1 Anna F 2604 1880

2 Emma F 2003 1880

3 Elizabeth F 1939 1880

4 Minnie F 1746 1880

5 Margaret F 1578 1880

6 Ida F 1472 1880

7 Alice F 1414 1880

8 Bertha F 1320 1880

9 Sarah F 1288 1880There are many things you might want to do with the dataset:

Visualize the proportion of babies given a particular name (your own, or another name) over time

Determine the relative rank of a name

Determine the most popular names in each year or the names whose popularity has advanced or declined the most

Analyze trends in names: vowels, consonants, length, overall diversity, changes in spelling, first and last letters

Analyze external sources of trends: biblical names, celebrities, demographics

With the tools in this book, many of these kinds of analyses are within reach, so I will walk you through some of them.

As of this writing, the US Social Security Administration makes available data files, one per year, containing the total number of births for each sex/name combination. You can download the raw archive of these files.

If this page has been moved by the time you’re reading this, it can most likely be located again with an internet search. After downloading the “National data” file names.zip and unzipping it, you will have a directory containing a series of files like yob1880.txt. I use the Unix head command to look at the first 10 lines of one of the files (on Windows, you can use the more command or open it in a text editor):

In [106]: !head -n 10 datasets/babynames/yob1880.txt

Mary,F,7065

Anna,F,2604

Emma,F,2003

Elizabeth,F,1939

Minnie,F,1746

Margaret,F,1578

Ida,F,1472

Alice,F,1414

Bertha,F,1320

Sarah,F,1288As this is already in comma-separated form, it can be loaded into a DataFrame with pandas.read_csv:

In [107]: names1880 = pd.read_csv("datasets/babynames/yob1880.txt",

.....: names=["name", "sex", "births"])

In [108]: names1880

Out[108]:

name sex births

0 Mary F 7065

1 Anna F 2604

2 Emma F 2003

3 Elizabeth F 1939

4 Minnie F 1746

... ... .. ...

1995 Woodie M 5

1996 Worthy M 5

1997 Wright M 5

1998 York M 5

1999 Zachariah M 5

[2000 rows x 3 columns]These files only contain names with at least five occurrences in each year, so for simplicity’s sake we can use the sum of the births column by sex as the total number of births in that year:

In [109]: names1880.groupby("sex")["births"].sum()

Out[109]:

sex

F 90993

M 110493

Name: births, dtype: int64Since the dataset is split into files by year, one of the first things to do is to assemble all of the data into a single DataFrame and further add a year field. You can do this using pandas.concat. Run the following in a Jupyter cell:

pieces = []

for year in range(1880, 2011):

path = f"datasets/babynames/yob{year}.txt"

frame = pd.read_csv(path, names=["name", "sex", "births"])

# Add a column for the year

frame["year"] = year

pieces.append(frame)

# Concatenate everything into a single DataFrame

names = pd.concat(pieces, ignore_index=True)There are a couple things to note here. First, remember that concat combines the DataFrame objects by row by default. Second, you have to pass ignore_index=True because we’re not interested in preserving the original row numbers returned from pandas.read_csv. So we now have a single DataFrame containing all of the names data across all years:

In [111]: names

Out[111]:

name sex births year

0 Mary F 7065 1880

1 Anna F 2604 1880

2 Emma F 2003 1880

3 Elizabeth F 1939 1880

4 Minnie F 1746 1880

... ... .. ... ...

1690779 Zymaire M 5 2010

1690780 Zyonne M 5 2010

1690781 Zyquarius M 5 2010

1690782 Zyran M 5 2010

1690783 Zzyzx M 5 2010

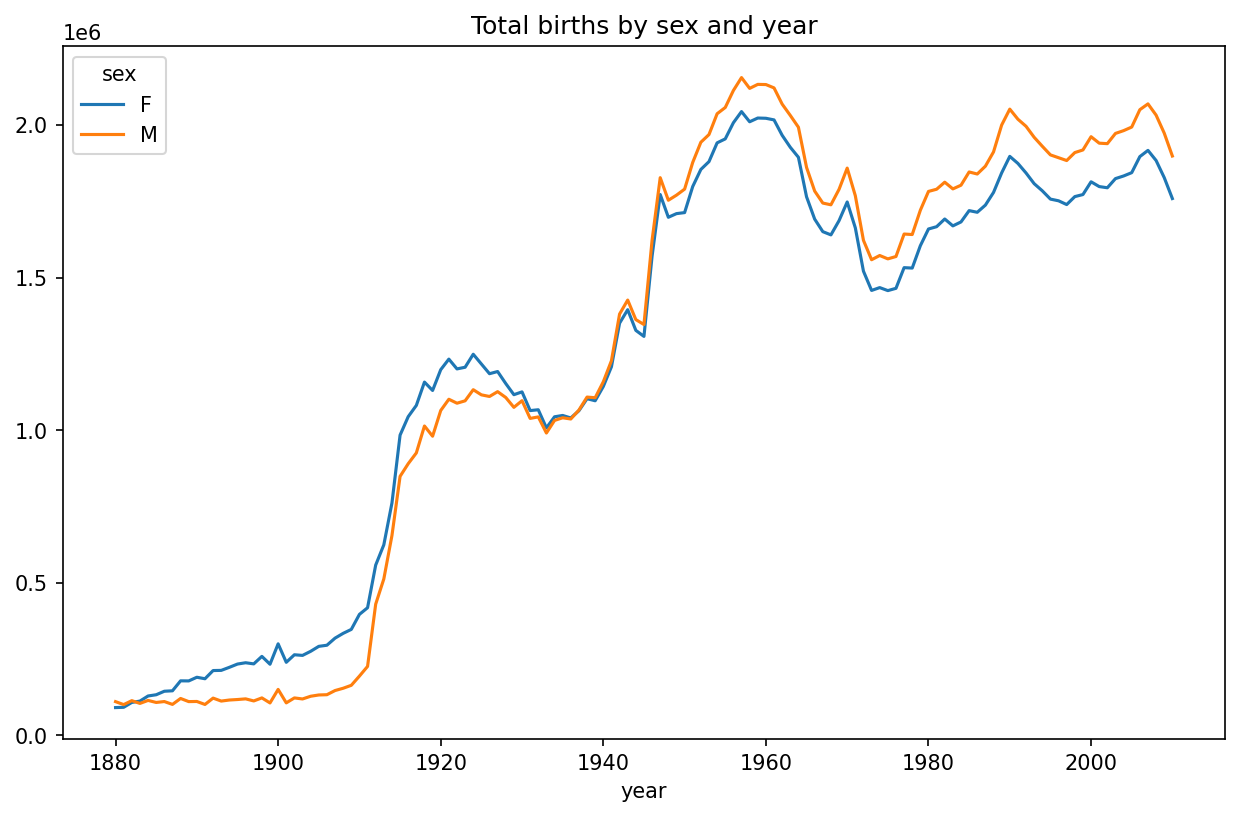

[1690784 rows x 4 columns]With this data in hand, we can already start aggregating the data at the year and sex level using groupby or pivot_table (see Total births by sex and year):

In [112]: total_births = names.pivot_table("births", index="year",

.....: columns="sex", aggfunc=sum)

In [113]: total_births.tail()

Out[113]:

sex F M

year

2006 1896468 2050234

2007 1916888 2069242

2008 1883645 2032310

2009 1827643 1973359

2010 1759010 1898382

In [114]: total_births.plot(title="Total births by sex and year")

Next, let’s insert a column prop with the fraction of babies given each name relative to the total number of births. A prop value of 0.02 would indicate that 2 out of every 100 babies were given a particular name. Thus, we group the data by year and sex, then add the new column to each group:

def add_prop(group):

group["prop"] = group["births"] / group["births"].sum()

return group

names = names.groupby(["year", "sex"], group_keys=False).apply(add_prop)The resulting complete dataset now has the following columns:

In [116]: names

Out[116]:

name sex births year prop

0 Mary F 7065 1880 0.077643

1 Anna F 2604 1880 0.028618

2 Emma F 2003 1880 0.022013

3 Elizabeth F 1939 1880 0.021309

4 Minnie F 1746 1880 0.019188

... ... .. ... ... ...

1690779 Zymaire M 5 2010 0.000003

1690780 Zyonne M 5 2010 0.000003

1690781 Zyquarius M 5 2010 0.000003

1690782 Zyran M 5 2010 0.000003

1690783 Zzyzx M 5 2010 0.000003

[1690784 rows x 5 columns]When performing a group operation like this, it's often valuable to do a sanity check, like verifying that the prop column sums to 1 within all the groups:

In [117]: names.groupby(["year", "sex"])["prop"].sum()

Out[117]:

year sex

1880 F 1.0

M 1.0

1881 F 1.0

M 1.0

1882 F 1.0

...

2008 M 1.0

2009 F 1.0

M 1.0

2010 F 1.0

M 1.0

Name: prop, Length: 262, dtype: float64Now that this is done, I’m going to extract a subset of the data to facilitate further analysis: the top 1,000 names for each sex/year combination. This is yet another group operation:

In [118]: def get_top1000(group):

.....: return group.sort_values("births", ascending=False)[:1000]

In [119]: grouped = names.groupby(["year", "sex"])

In [120]: top1000 = grouped.apply(get_top1000)

In [121]: top1000.head()

Out[121]:

name sex births year prop

year sex

1880 F 0 Mary F 7065 1880 0.077643

1 Anna F 2604 1880 0.028618

2 Emma F 2003 1880 0.022013

3 Elizabeth F 1939 1880 0.021309

4 Minnie F 1746 1880 0.019188We can drop the group index since we don't need it for our analysis:

In [122]: top1000 = top1000.reset_index(drop=True)The resulting dataset is now quite a bit smaller:

In [123]: top1000.head()

Out[123]:

name sex births year prop

0 Mary F 7065 1880 0.077643

1 Anna F 2604 1880 0.028618

2 Emma F 2003 1880 0.022013

3 Elizabeth F 1939 1880 0.021309

4 Minnie F 1746 1880 0.019188We’ll use this top one thousand dataset in the following investigations into the data.

Analyzing Naming Trends

With the full dataset and the top one thousand dataset in hand, we can start analyzing various naming trends of interest. First, we can split the top one thousand names into the boy and girl portions:

In [124]: boys = top1000[top1000["sex"] == "M"]

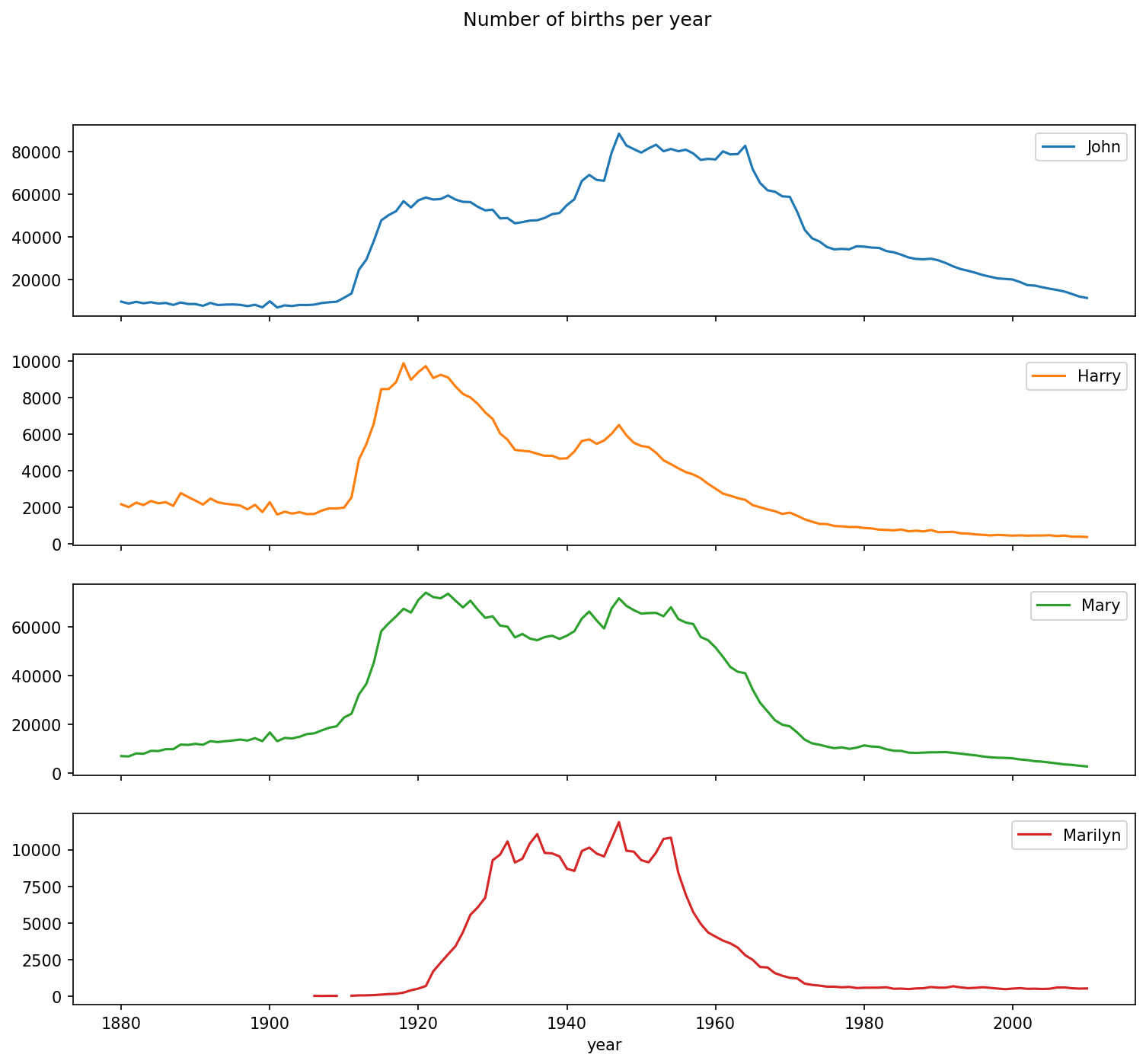

In [125]: girls = top1000[top1000["sex"] == "F"]Simple time series, like the number of Johns or Marys for each year, can be plotted but require some manipulation to be more useful. Let’s form a pivot table of the total number of births by year and name:

In [126]: total_births = top1000.pivot_table("births", index="year",

.....: columns="name",

.....: aggfunc=sum)Now, this can be plotted for a handful of names with DataFrame’s plot method (A few boy and girl names over time shows the result):

In [127]: total_births.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 131 entries, 1880 to 2010

Columns: 6868 entries, Aaden to Zuri

dtypes: float64(6868)

memory usage: 6.9 MB

In [128]: subset = total_births[["John", "Harry", "Mary", "Marilyn"]]

In [129]: subset.plot(subplots=True, figsize=(12, 10),

.....: title="Number of births per year")

On looking at this, you might conclude that these names have grown out of favor with the American population. But the story is actually more complicated than that, as will be explored in the next section.

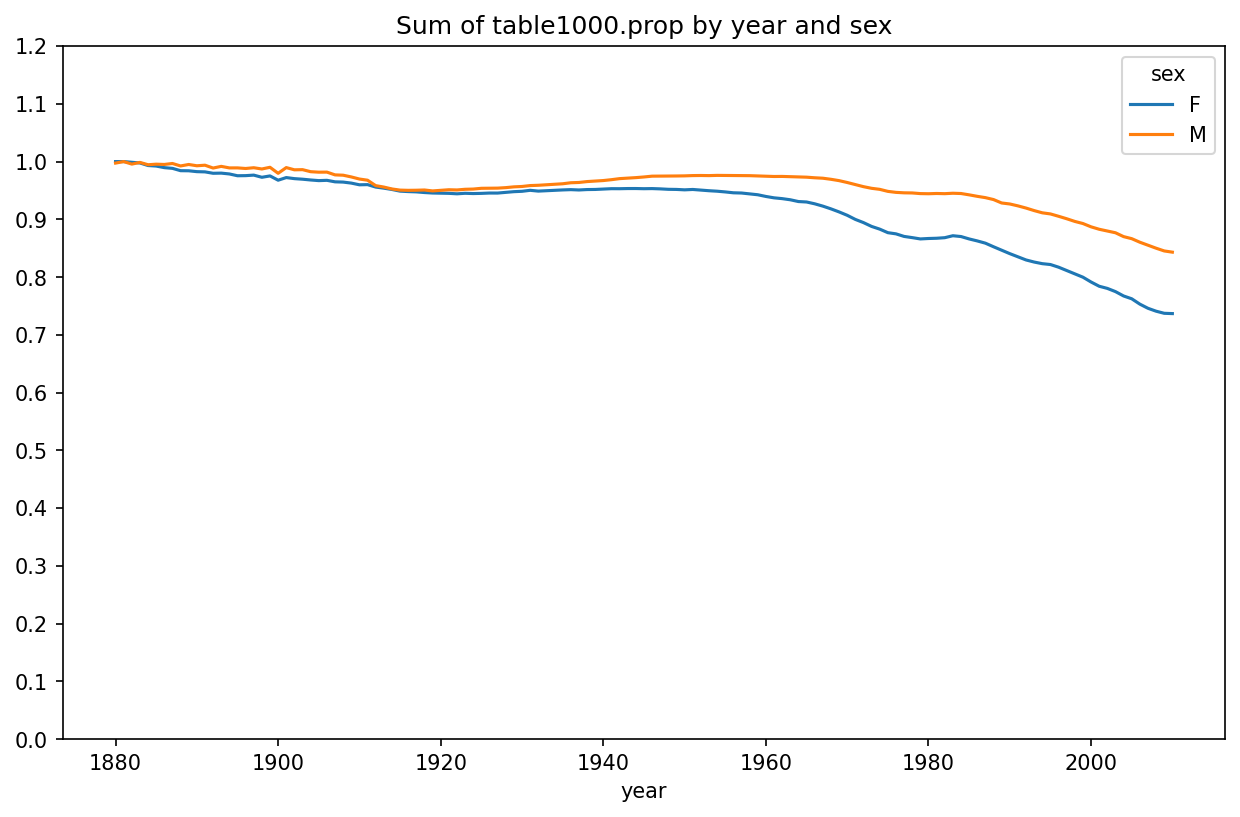

Measuring the increase in naming diversity

One explanation for the decrease in plots is that fewer parents are choosing common names for their children. This hypothesis can be explored and confirmed in the data. One measure is the proportion of births represented by the top 1,000 most popular names, which I aggregate and plot by year and sex (Proportion of births represented in top one thousand names by sex shows the resulting plot):

In [131]: table = top1000.pivot_table("prop", index="year",

.....: columns="sex", aggfunc=sum)

In [132]: table.plot(title="Sum of table1000.prop by year and sex",

.....: yticks=np.linspace(0, 1.2, 13))

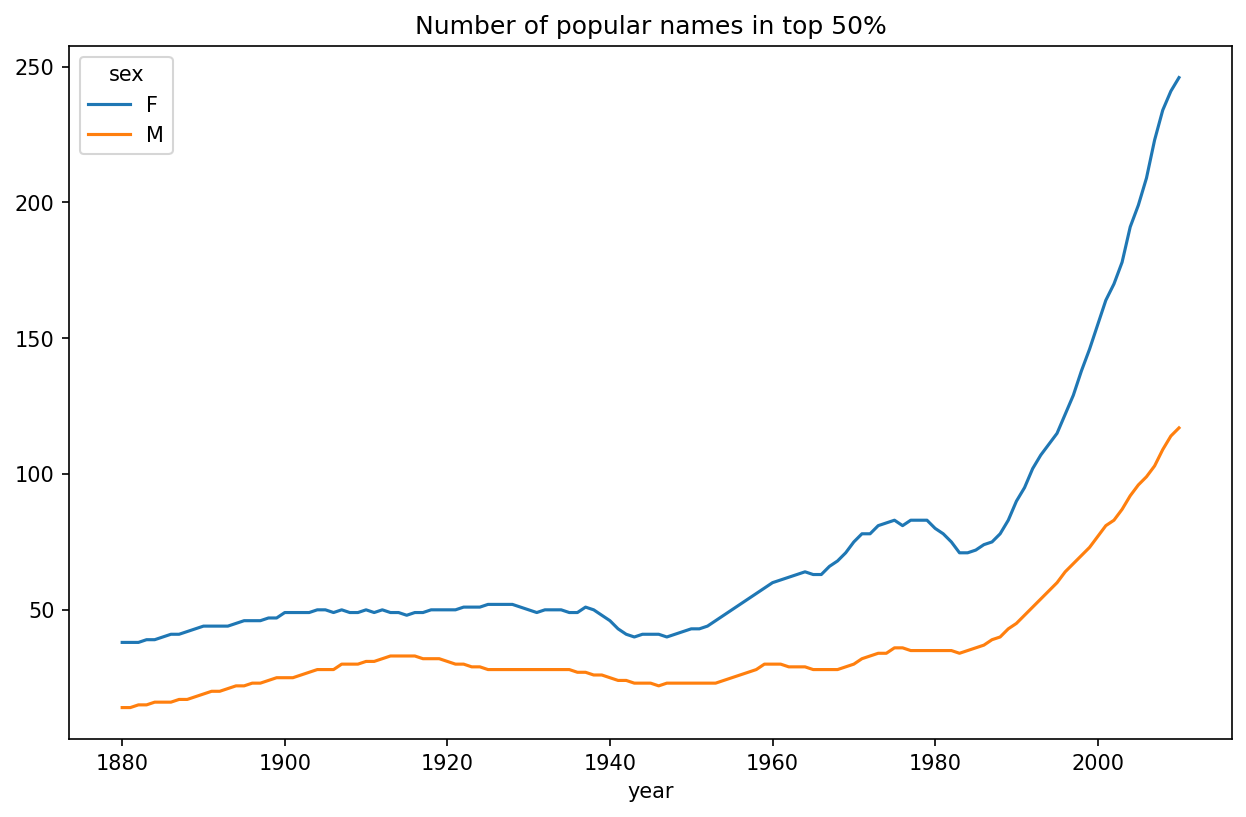

You can see that, indeed, there appears to be increasing name diversity (decreasing total proportion in the top one thousand). Another interesting metric is the number of distinct names, taken in order of popularity from highest to lowest, in the top 50% of births. This number is trickier to compute. Let’s consider just the boy names from 2010:

In [133]: df = boys[boys["year"] == 2010]

In [134]: df

Out[134]:

name sex births year prop

260877 Jacob M 21875 2010 0.011523

260878 Ethan M 17866 2010 0.009411

260879 Michael M 17133 2010 0.009025

260880 Jayden M 17030 2010 0.008971

260881 William M 16870 2010 0.008887

... ... .. ... ... ...

261872 Camilo M 194 2010 0.000102

261873 Destin M 194 2010 0.000102

261874 Jaquan M 194 2010 0.000102

261875 Jaydan M 194 2010 0.000102

261876 Maxton M 193 2010 0.000102

[1000 rows x 5 columns]After sorting prop in descending order, we want to know how many of the most popular names it takes to reach 50%. You could write a for loop to do this, but a vectorized NumPy way is more computationally efficient. Taking the cumulative sum, cumsum, of prop and then calling the method searchsorted returns the position in the cumulative sum at which 0.5 would need to be inserted to keep it in sorted order:

In [135]: prop_cumsum = df["prop"].sort_values(ascending=False).cumsum()

In [136]: prop_cumsum[:10]

Out[136]:

260877 0.011523

260878 0.020934

260879 0.029959

260880 0.038930

260881 0.047817

260882 0.056579

260883 0.065155

260884 0.073414

260885 0.081528

260886 0.089621

Name: prop, dtype: float64

In [137]: prop_cumsum.searchsorted(0.5)

Out[137]: 116Since arrays are zero-indexed, adding 1 to this result gives you a result of 117. By contrast, in 1900 this number was much smaller:

In [138]: df = boys[boys.year == 1900]

In [139]: in1900 = df.sort_values("prop", ascending=False).prop.cumsum()

In [140]: in1900.searchsorted(0.5) + 1

Out[140]: 25You can now apply this operation to each year/sex combination, groupby those fields, and apply a function returning the count for each group:

def get_quantile_count(group, q=0.5):

group = group.sort_values("prop", ascending=False)

return group.prop.cumsum().searchsorted(q) + 1

diversity = top1000.groupby(["year", "sex"]).apply(get_quantile_count)

diversity = diversity.unstack()This resulting DataFrame diversity now has two time series, one for each sex, indexed by year. This can be inspected and plotted as before (see Plot of diversity metric by year):

In [143]: diversity.head()

Out[143]:

sex F M

year

1880 38 14

1881 38 14

1882 38 15

1883 39 15

1884 39 16

In [144]: diversity.plot(title="Number of popular names in top 50%")

As you can see, girl names have always been more diverse than boy names, and they have only become more so over time. Further analysis of what exactly is driving the diversity, like the increase of alternative spellings, is left to the reader.

The “last letter” revolution

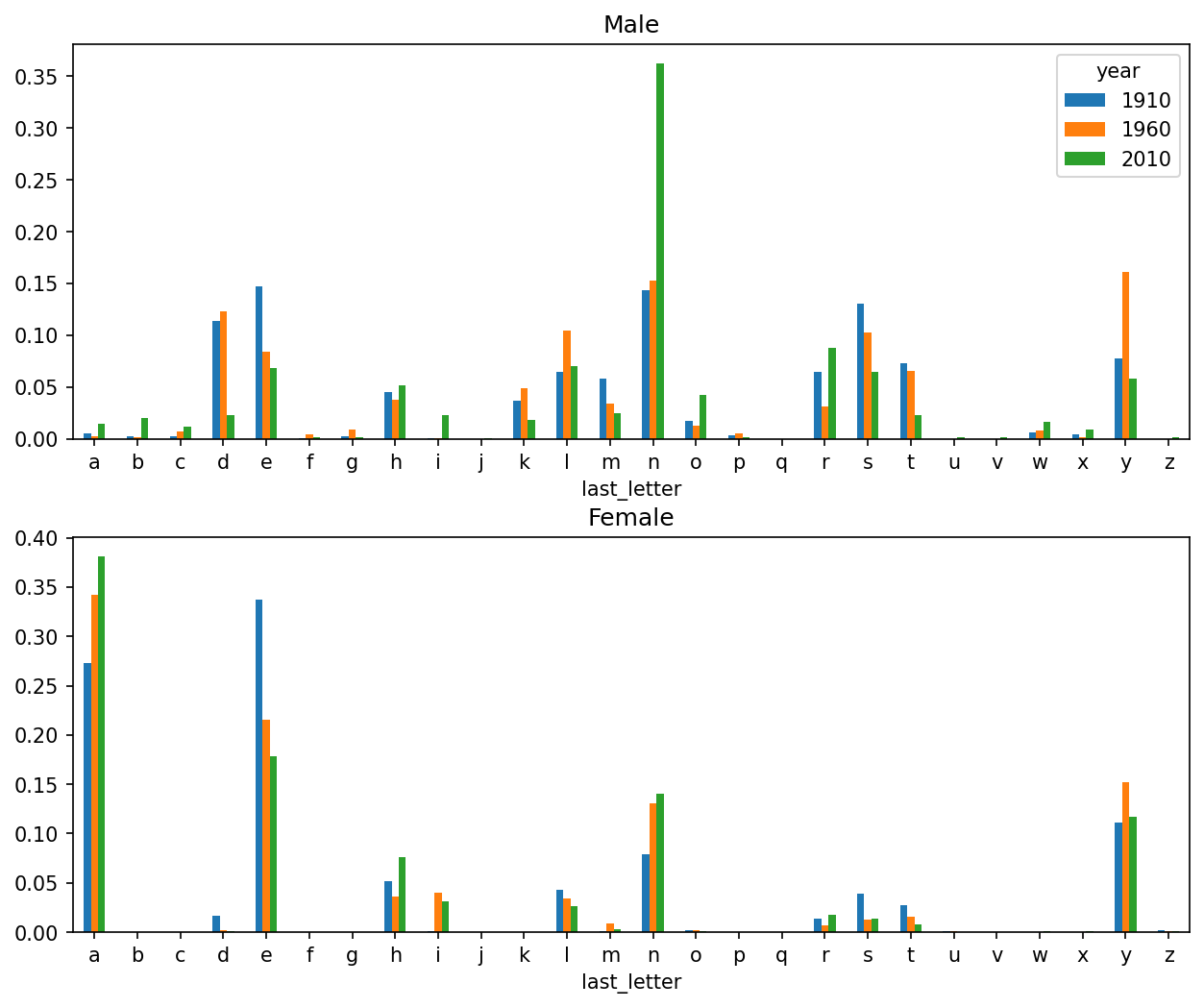

In 2007, baby name researcher Laura Wattenberg pointed out that the distribution of boy names by final letter has changed significantly over the last 100 years. To see this, we first aggregate all of the births in the full dataset by year, sex, and final letter:

def get_last_letter(x):

return x[-1]

last_letters = names["name"].map(get_last_letter)

last_letters.name = "last_letter"

table = names.pivot_table("births", index=last_letters,

columns=["sex", "year"], aggfunc=sum)Then we select three representative years spanning the history and print the first few rows:

In [146]: subtable = table.reindex(columns=[1910, 1960, 2010], level="year")

In [147]: subtable.head()

Out[147]:

sex F M

year 1910 1960 2010 1910 1960 2010

last_letter

a 108376.0 691247.0 670605.0 977.0 5204.0 28438.0

b NaN 694.0 450.0 411.0 3912.0 38859.0

c 5.0 49.0 946.0 482.0 15476.0 23125.0

d 6750.0 3729.0 2607.0 22111.0 262112.0 44398.0

e 133569.0 435013.0 313833.0 28655.0 178823.0 129012.0Next, normalize the table by total births to compute a new table containing the proportion of total births for each sex ending in each letter:

In [148]: subtable.sum()

Out[148]:

sex year

F 1910 396416.0

1960 2022062.0

2010 1759010.0

M 1910 194198.0

1960 2132588.0

2010 1898382.0

dtype: float64

In [149]: letter_prop = subtable / subtable.sum()

In [150]: letter_prop

Out[150]:

sex F M

year 1910 1960 2010 1910 1960 2010

last_letter

a 0.273390 0.341853 0.381240 0.005031 0.002440 0.014980

b NaN 0.000343 0.000256 0.002116 0.001834 0.020470

c 0.000013 0.000024 0.000538 0.002482 0.007257 0.012181

d 0.017028 0.001844 0.001482 0.113858 0.122908 0.023387

e 0.336941 0.215133 0.178415 0.147556 0.083853 0.067959

... ... ... ... ... ... ...

v NaN 0.000060 0.000117 0.000113 0.000037 0.001434

w 0.000020 0.000031 0.001182 0.006329 0.007711 0.016148

x 0.000015 0.000037 0.000727 0.003965 0.001851 0.008614

y 0.110972 0.152569 0.116828 0.077349 0.160987 0.058168

z 0.002439 0.000659 0.000704 0.000170 0.000184 0.001831

[26 rows x 6 columns]With the letter proportions now in hand, we can make bar plots for each sex, broken down by year (see Proportion of boy and girl names ending in each letter):

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(10, 8))

letter_prop["M"].plot(kind="bar", rot=0, ax=axes[0], title="Male")

letter_prop["F"].plot(kind="bar", rot=0, ax=axes[1], title="Female",

legend=False)

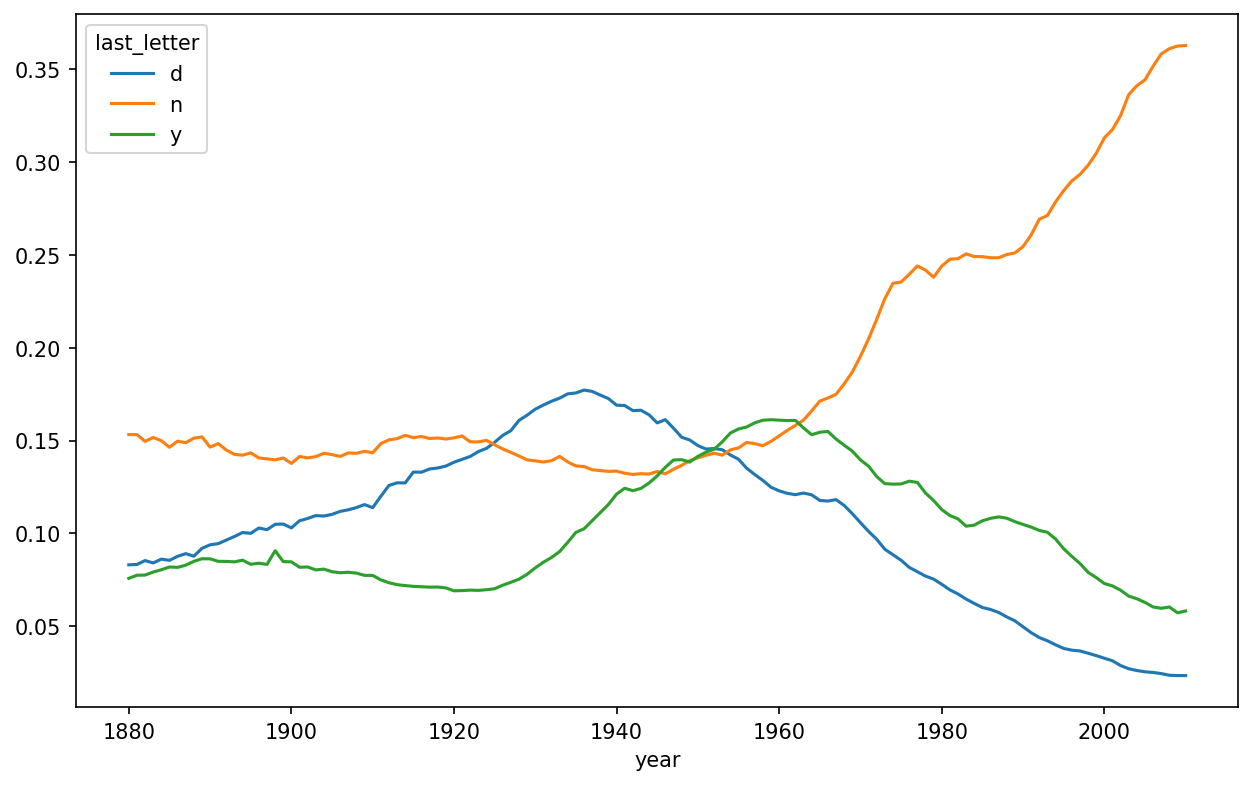

As you can see, boy names ending in n have experienced significant growth since the 1960s. Going back to the full table created before, I again normalize by year and sex and select a subset of letters for the boy names, finally transposing to make each column a time series:

In [153]: letter_prop = table / table.sum()

In [154]: dny_ts = letter_prop.loc[["d", "n", "y"], "M"].T

In [155]: dny_ts.head()

Out[155]:

last_letter d n y

year

1880 0.083055 0.153213 0.075760

1881 0.083247 0.153214 0.077451

1882 0.085340 0.149560 0.077537

1883 0.084066 0.151646 0.079144

1884 0.086120 0.149915 0.080405With this DataFrame of time series in hand, I can make a plot of the trends over time again with its plot method (see Proportion of boys born with names ending in d/n/y over time):

In [158]: dny_ts.plot()

Boy names that became girl names (and vice versa)

Another fun trend is looking at names that were more popular with one gender earlier in the sample but have become preferred as a name for the other gender over time. One example is the name Lesley or Leslie. Going back to the top1000 DataFrame, I compute a list of names occurring in the dataset starting with "Lesl":

In [159]: all_names = pd.Series(top1000["name"].unique())

In [160]: lesley_like = all_names[all_names.str.contains("Lesl")]

In [161]: lesley_like

Out[161]:

632 Leslie

2294 Lesley

4262 Leslee

4728 Lesli

6103 Lesly

dtype: objectFrom there, we can filter down to just those names and sum births grouped by name to see the relative frequencies:

In [162]: filtered = top1000[top1000["name"].isin(lesley_like)]

In [163]: filtered.groupby("name")["births"].sum()

Out[163]:

name

Leslee 1082

Lesley 35022

Lesli 929

Leslie 370429

Lesly 10067

Name: births, dtype: int64Next, let’s aggregate by sex and year, and normalize within year:

In [164]: table = filtered.pivot_table("births", index="year",

.....: columns="sex", aggfunc="sum")

In [165]: table = table.div(table.sum(axis="columns"), axis="index")

In [166]: table.tail()

Out[166]:

sex F M

year

2006 1.0 NaN

2007 1.0 NaN

2008 1.0 NaN

2009 1.0 NaN

2010 1.0 NaNLastly, it’s now possible to make a plot of the breakdown by sex over time (see Proportion of male/female Lesley-like names over time):

In [168]: table.plot(style={"M": "k-", "F": "k--"})

13.4 USDA Food Database

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) makes available a database of food nutrient information. Programmer Ashley Williams created a version of this database in JSON format. The records look like this:

{

"id": 21441,

"description": "KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN, Fried Chicken, EXTRA CRISPY,

Wing, meat and skin with breading",

"tags": ["KFC"],

"manufacturer": "Kentucky Fried Chicken",

"group": "Fast Foods",

"portions": [

{

"amount": 1,

"unit": "wing, with skin",

"grams": 68.0

},

...

],

"nutrients": [

{

"value": 20.8,

"units": "g",

"description": "Protein",

"group": "Composition"

},

...

]

}Each food has a number of identifying attributes along with two lists of nutrients and portion sizes. Data in this form is not particularly amenable to analysis, so we need to do some work to wrangle the data into a better form.

You can load this file into Python with any JSON library of your choosing. I’ll use the built-in Python json module:

In [169]: import json

In [170]: db = json.load(open("datasets/usda_food/database.json"))

In [171]: len(db)

Out[171]: 6636Each entry in db is a dictionary containing all the data for a single food. The "nutrients" field is a list of dictionaries, one for each nutrient:

In [172]: db[0].keys()

Out[172]: dict_keys(['id', 'description', 'tags', 'manufacturer', 'group', 'porti

ons', 'nutrients'])

In [173]: db[0]["nutrients"][0]

Out[173]:

{'value': 25.18,

'units': 'g',

'description': 'Protein',

'group': 'Composition'}

In [174]: nutrients = pd.DataFrame(db[0]["nutrients"])

In [175]: nutrients.head(7)

Out[175]:

value units description group

0 25.18 g Protein Composition

1 29.20 g Total lipid (fat) Composition

2 3.06 g Carbohydrate, by difference Composition

3 3.28 g Ash Other

4 376.00 kcal Energy Energy

5 39.28 g Water Composition

6 1573.00 kJ Energy EnergyWhen converting a list of dictionaries to a DataFrame, we can specify a list of fields to extract. We’ll take the food names, group, ID, and manufacturer:

In [176]: info_keys = ["description", "group", "id", "manufacturer"]

In [177]: info = pd.DataFrame(db, columns=info_keys)

In [178]: info.head()

Out[178]:

description group id

0 Cheese, caraway Dairy and Egg Products 1008 \

1 Cheese, cheddar Dairy and Egg Products 1009

2 Cheese, edam Dairy and Egg Products 1018

3 Cheese, feta Dairy and Egg Products 1019

4 Cheese, mozzarella, part skim milk Dairy and Egg Products 1028

manufacturer

0

1

2

3

4

In [179]: info.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 6636 entries, 0 to 6635

Data columns (total 4 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 description 6636 non-null object

1 group 6636 non-null object

2 id 6636 non-null int64

3 manufacturer 5195 non-null object

dtypes: int64(1), object(3)

memory usage: 207.5+ KBFrom the output of info.info(), we can see that there is missing data in the manufacturer column.

You can see the distribution of food groups with value_counts:

In [180]: pd.value_counts(info["group"])[:10]

Out[180]:

group

Vegetables and Vegetable Products 812

Beef Products 618

Baked Products 496

Breakfast Cereals 403

Legumes and Legume Products 365

Fast Foods 365

Lamb, Veal, and Game Products 345

Sweets 341

Fruits and Fruit Juices 328

Pork Products 328

Name: count, dtype: int64Now, to do some analysis on all of the nutrient data, it’s easiest to assemble the nutrients for each food into a single large table. To do so, we need to take several steps. First, I’ll convert each list of food nutrients to a DataFrame, add a column for the food id, and append the DataFrame to a list. Then, these can be concatenated with concat. Run the following code in a Jupyter cell:

nutrients = []

for rec in db:

fnuts = pd.DataFrame(rec["nutrients"])

fnuts["id"] = rec["id"]

nutrients.append(fnuts)

nutrients = pd.concat(nutrients, ignore_index=True)If all goes well, nutrients should look like this:

In [182]: nutrients

Out[182]:

value units description group id

0 25.180 g Protein Composition 1008

1 29.200 g Total lipid (fat) Composition 1008

2 3.060 g Carbohydrate, by difference Composition 1008

3 3.280 g Ash Other 1008

4 376.000 kcal Energy Energy 1008

... ... ... ... ... ...

389350 0.000 mcg Vitamin B-12, added Vitamins 43546

389351 0.000 mg Cholesterol Other 43546

389352 0.072 g Fatty acids, total saturated Other 43546

389353 0.028 g Fatty acids, total monounsaturated Other 43546

389354 0.041 g Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated Other 43546

[389355 rows x 5 columns]I noticed that there are duplicates in this DataFrame, so it makes things easier to drop them:

In [183]: nutrients.duplicated().sum() # number of duplicates

Out[183]: 14179

In [184]: nutrients = nutrients.drop_duplicates()Since "group" and "description" are in both DataFrame objects, we can rename for clarity:

In [185]: col_mapping = {"description" : "food",

.....: "group" : "fgroup"}

In [186]: info = info.rename(columns=col_mapping, copy=False)

In [187]: info.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 6636 entries, 0 to 6635

Data columns (total 4 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 food 6636 non-null object

1 fgroup 6636 non-null object

2 id 6636 non-null int64

3 manufacturer 5195 non-null object

dtypes: int64(1), object(3)

memory usage: 207.5+ KB

In [188]: col_mapping = {"description" : "nutrient",

.....: "group" : "nutgroup"}

In [189]: nutrients = nutrients.rename(columns=col_mapping, copy=False)

In [190]: nutrients

Out[190]:

value units nutrient nutgroup id

0 25.180 g Protein Composition 1008

1 29.200 g Total lipid (fat) Composition 1008

2 3.060 g Carbohydrate, by difference Composition 1008

3 3.280 g Ash Other 1008

4 376.000 kcal Energy Energy 1008

... ... ... ... ... ...

389350 0.000 mcg Vitamin B-12, added Vitamins 43546

389351 0.000 mg Cholesterol Other 43546

389352 0.072 g Fatty acids, total saturated Other 43546

389353 0.028 g Fatty acids, total monounsaturated Other 43546

389354 0.041 g Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated Other 43546

[375176 rows x 5 columns]With all of this done, we’re ready to merge info with nutrients:

In [191]: ndata = pd.merge(nutrients, info, on="id")

In [192]: ndata.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 375176 entries, 0 to 375175

Data columns (total 8 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 value 375176 non-null float64

1 units 375176 non-null object

2 nutrient 375176 non-null object

3 nutgroup 375176 non-null object

4 id 375176 non-null int64

5 food 375176 non-null object

6 fgroup 375176 non-null object

7 manufacturer 293054 non-null object

dtypes: float64(1), int64(1), object(6)

memory usage: 22.9+ MB

In [193]: ndata.iloc[30000]

Out[193]:

value 0.04

units g

nutrient Glycine

nutgroup Amino Acids

id 6158

food Soup, tomato bisque, canned, condensed

fgroup Soups, Sauces, and Gravies

manufacturer

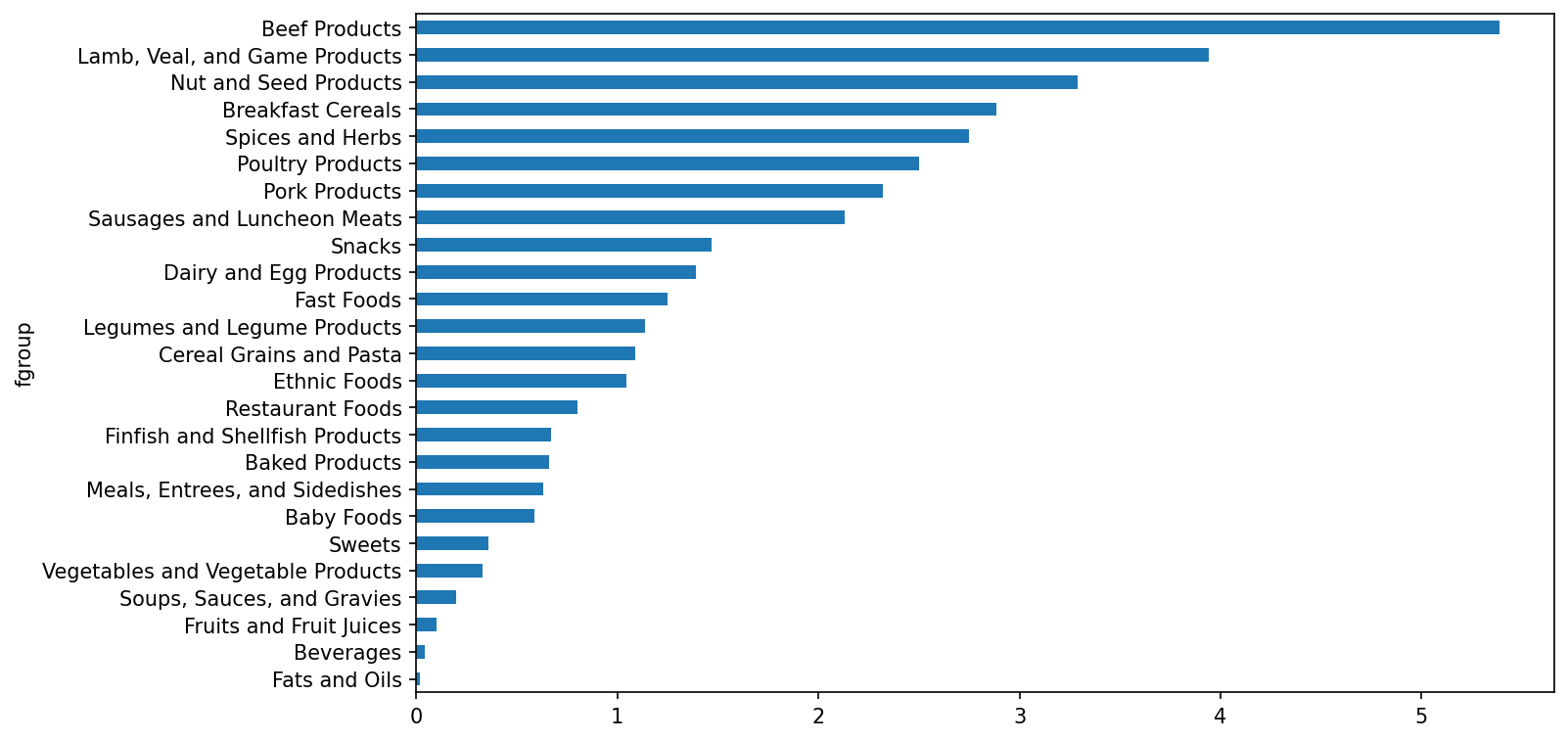

Name: 30000, dtype: objectWe could now make a plot of median values by food group and nutrient type (see Median zinc values by food group):

In [195]: result = ndata.groupby(["nutrient", "fgroup"])["value"].quantile(0.5)

In [196]: result["Zinc, Zn"].sort_values().plot(kind="barh")

Using the idxmax or argmax Series methods, you can find which food is most dense in each nutrient. Run the following in a Jupyter cell:

by_nutrient = ndata.groupby(["nutgroup", "nutrient"])

def get_maximum(x):

return x.loc[x.value.idxmax()]

max_foods = by_nutrient.apply(get_maximum)[["value", "food"]]

# make the food a little smaller

max_foods["food"] = max_foods["food"].str[:50]The resulting DataFrame is a bit too large to display in the book; here is only the "Amino Acids" nutrient group:

In [198]: max_foods.loc["Amino Acids"]["food"]

Out[198]:

nutrient

Alanine Gelatins, dry powder, unsweetened

Arginine Seeds, sesame flour, low-fat

Aspartic acid Soy protein isolate

Cystine Seeds, cottonseed flour, low fat (glandless)

Glutamic acid Soy protein isolate

Glycine Gelatins, dry powder, unsweetened

Histidine Whale, beluga, meat, dried (Alaska Native)

Hydroxyproline KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN, Fried Chicken, ORIGINAL RE

Isoleucine Soy protein isolate, PROTEIN TECHNOLOGIES INTERNAT

Leucine Soy protein isolate, PROTEIN TECHNOLOGIES INTERNAT

Lysine Seal, bearded (Oogruk), meat, dried (Alaska Native

Methionine Fish, cod, Atlantic, dried and salted

Phenylalanine Soy protein isolate, PROTEIN TECHNOLOGIES INTERNAT

Proline Gelatins, dry powder, unsweetened

Serine Soy protein isolate, PROTEIN TECHNOLOGIES INTERNAT

Threonine Soy protein isolate, PROTEIN TECHNOLOGIES INTERNAT

Tryptophan Sea lion, Steller, meat with fat (Alaska Native)

Tyrosine Soy protein isolate, PROTEIN TECHNOLOGIES INTERNAT

Valine Soy protein isolate, PROTEIN TECHNOLOGIES INTERNAT

Name: food, dtype: object13.5 2012 Federal Election Commission Database

The US Federal Election Commission (FEC) publishes data on contributions to political campaigns. This includes contributor names, occupation and employer, address, and contribution amount. The contribution data from the 2012 US presidential election was available as a single 150-megabyte CSV file P00000001-ALL.csv (see the book's data repository), which can be loaded with pandas.read_csv:

In [199]: fec = pd.read_csv("datasets/fec/P00000001-ALL.csv", low_memory=False)

In [200]: fec.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 1001731 entries, 0 to 1001730

Data columns (total 16 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 cmte_id 1001731 non-null object

1 cand_id 1001731 non-null object

2 cand_nm 1001731 non-null object

3 contbr_nm 1001731 non-null object

4 contbr_city 1001712 non-null object

5 contbr_st 1001727 non-null object

6 contbr_zip 1001620 non-null object

7 contbr_employer 988002 non-null object

8 contbr_occupation 993301 non-null object

9 contb_receipt_amt 1001731 non-null float64

10 contb_receipt_dt 1001731 non-null object

11 receipt_desc 14166 non-null object

12 memo_cd 92482 non-null object

13 memo_text 97770 non-null object

14 form_tp 1001731 non-null object

15 file_num 1001731 non-null int64

dtypes: float64(1), int64(1), object(14)

memory usage: 122.3+ MBSeveral people asked me to update the dataset from the 2012 election to the 2016 or 2020 elections. Unfortunately, the more recent datasets provided by the FEC have become larger and more complex, and I decided that working with them here would be a distraction from the analysis techniques that I wanted to illustrate.

A sample record in the DataFrame looks like this:

In [201]: fec.iloc[123456]

Out[201]:

cmte_id C00431445

cand_id P80003338

cand_nm Obama, Barack

contbr_nm ELLMAN, IRA

contbr_city TEMPE

contbr_st AZ

contbr_zip 852816719

contbr_employer ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY

contbr_occupation PROFESSOR

contb_receipt_amt 50.0

contb_receipt_dt 01-DEC-11

receipt_desc NaN

memo_cd NaN

memo_text NaN

form_tp SA17A

file_num 772372

Name: 123456, dtype: objectYou may think of some ways to start slicing and dicing this data to extract informative statistics about donors and patterns in the campaign contributions. I’ll show you a number of different analyses that apply the techniques in this book.

You can see that there are no political party affiliations in the data, so this would be useful to add. You can get a list of all the unique political candidates using unique:

In [202]: unique_cands = fec["cand_nm"].unique()

In [203]: unique_cands

Out[203]:

array(['Bachmann, Michelle', 'Romney, Mitt', 'Obama, Barack',

"Roemer, Charles E. 'Buddy' III", 'Pawlenty, Timothy',

'Johnson, Gary Earl', 'Paul, Ron', 'Santorum, Rick',

'Cain, Herman', 'Gingrich, Newt', 'McCotter, Thaddeus G',

'Huntsman, Jon', 'Perry, Rick'], dtype=object)

In [204]: unique_cands[2]

Out[204]: 'Obama, Barack'One way to indicate party affiliation is using a dictionary:1

parties = {"Bachmann, Michelle": "Republican",

"Cain, Herman": "Republican",

"Gingrich, Newt": "Republican",

"Huntsman, Jon": "Republican",

"Johnson, Gary Earl": "Republican",

"McCotter, Thaddeus G": "Republican",

"Obama, Barack": "Democrat",

"Paul, Ron": "Republican",

"Pawlenty, Timothy": "Republican",

"Perry, Rick": "Republican",

"Roemer, Charles E. 'Buddy' III": "Republican",

"Romney, Mitt": "Republican",

"Santorum, Rick": "Republican"}Now, using this mapping and the map method on Series objects, you can compute an array of political parties from the candidate names:

In [206]: fec["cand_nm"][123456:123461]

Out[206]:

123456 Obama, Barack

123457 Obama, Barack

123458 Obama, Barack

123459 Obama, Barack

123460 Obama, Barack

Name: cand_nm, dtype: object

In [207]: fec["cand_nm"][123456:123461].map(parties)

Out[207]:

123456 Democrat

123457 Democrat

123458 Democrat

123459 Democrat

123460 Democrat

Name: cand_nm, dtype: object

# Add it as a column

In [208]: fec["party"] = fec["cand_nm"].map(parties)

In [209]: fec["party"].value_counts()

Out[209]:

party

Democrat 593746

Republican 407985

Name: count, dtype: int64A couple of data preparation points. First, this data includes both contributions and refunds (negative contribution amount):

In [210]: (fec["contb_receipt_amt"] > 0).value_counts()

Out[210]:

contb_receipt_amt

True 991475

False 10256

Name: count, dtype: int64To simplify the analysis, I’ll restrict the dataset to positive contributions:

In [211]: fec = fec[fec["contb_receipt_amt"] > 0]Since Barack Obama and Mitt Romney were the main two candidates, I’ll also prepare a subset that just has contributions to their campaigns:

In [212]: fec_mrbo = fec[fec["cand_nm"].isin(["Obama, Barack", "Romney, Mitt"])]Donation Statistics by Occupation and Employer

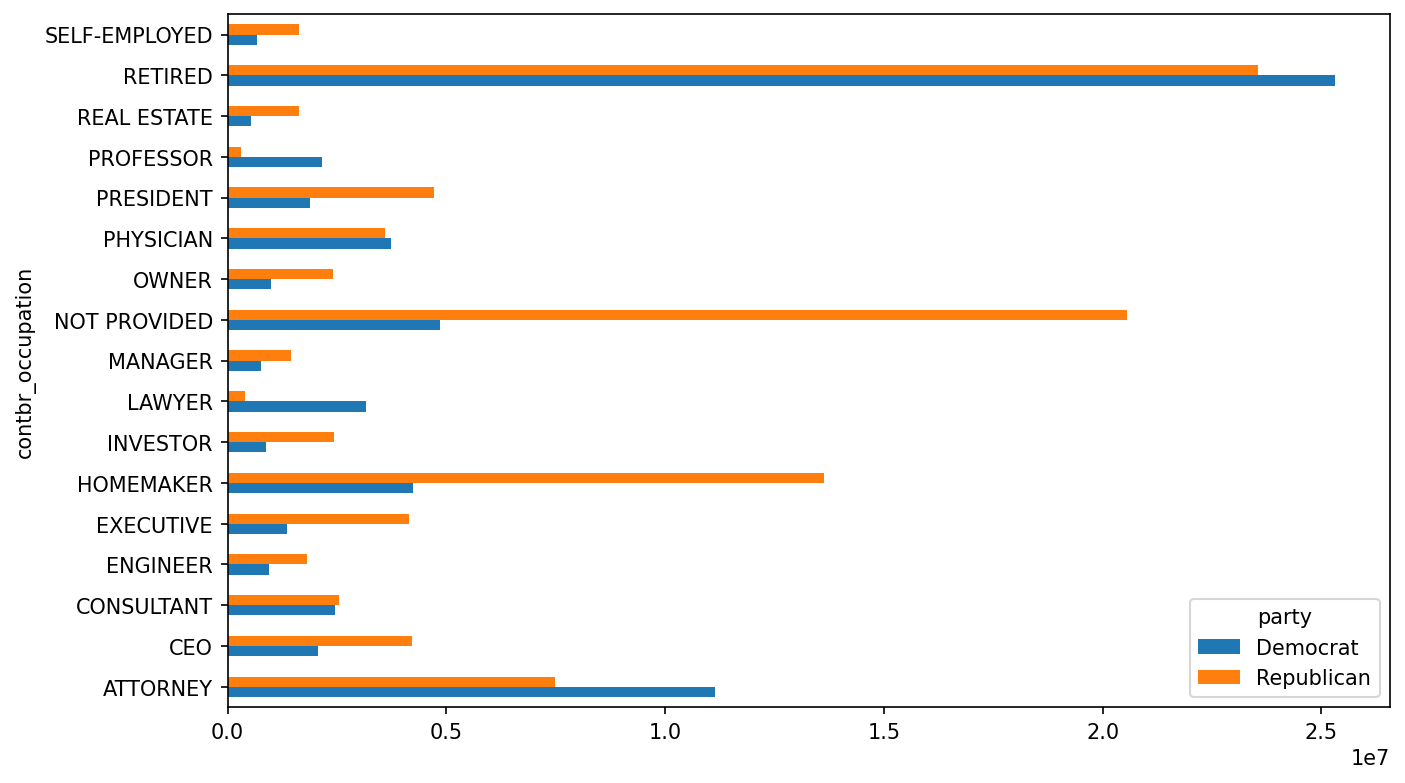

Donations by occupation is another oft-studied statistic. For example, attorneys tend to donate more money to Democrats, while business executives tend to donate more to Republicans. You have no reason to believe me; you can see for yourself in the data. First, the total number of donations by occupation can be computed with value_counts:

In [213]: fec["contbr_occupation"].value_counts()[:10]

Out[213]:

contbr_occupation

RETIRED 233990

INFORMATION REQUESTED 35107

ATTORNEY 34286

HOMEMAKER 29931

PHYSICIAN 23432

INFORMATION REQUESTED PER BEST EFFORTS 21138

ENGINEER 14334

TEACHER 13990

CONSULTANT 13273

PROFESSOR 12555

Name: count, dtype: int64You will notice by looking at the occupations that many refer to the same basic job type, or there are several variants of the same thing. The following code snippet illustrates a technique for cleaning up a few of them by mapping from one occupation to another; note the “trick” of using dict.get to allow occupations with no mapping to “pass through”:

occ_mapping = {

"INFORMATION REQUESTED PER BEST EFFORTS" : "NOT PROVIDED",

"INFORMATION REQUESTED" : "NOT PROVIDED",

"INFORMATION REQUESTED (BEST EFFORTS)" : "NOT PROVIDED",

"C.E.O.": "CEO"

}

def get_occ(x):

# If no mapping provided, return x

return occ_mapping.get(x, x)

fec["contbr_occupation"] = fec["contbr_occupation"].map(get_occ)I’ll also do the same thing for employers:

emp_mapping = {

"INFORMATION REQUESTED PER BEST EFFORTS" : "NOT PROVIDED",

"INFORMATION REQUESTED" : "NOT PROVIDED",

"SELF" : "SELF-EMPLOYED",

"SELF EMPLOYED" : "SELF-EMPLOYED",

}

def get_emp(x):

# If no mapping provided, return x

return emp_mapping.get(x, x)

fec["contbr_employer"] = fec["contbr_employer"].map(get_emp)Now, you can use pivot_table to aggregate the data by party and occupation, then filter down to the subset that donated at least $2 million overall:

In [216]: by_occupation = fec.pivot_table("contb_receipt_amt",

.....: index="contbr_occupation",

.....: columns="party", aggfunc="sum")

In [217]: over_2mm = by_occupation[by_occupation.sum(axis="columns") > 2000000]

In [218]: over_2mm

Out[218]:

party Democrat Republican

contbr_occupation

ATTORNEY 11141982.97 7477194.43

CEO 2074974.79 4211040.52

CONSULTANT 2459912.71 2544725.45

ENGINEER 951525.55 1818373.70

EXECUTIVE 1355161.05 4138850.09

HOMEMAKER 4248875.80 13634275.78

INVESTOR 884133.00 2431768.92

LAWYER 3160478.87 391224.32

MANAGER 762883.22 1444532.37

NOT PROVIDED 4866973.96 20565473.01

OWNER 1001567.36 2408286.92

PHYSICIAN 3735124.94 3594320.24

PRESIDENT 1878509.95 4720923.76

PROFESSOR 2165071.08 296702.73

REAL ESTATE 528902.09 1625902.25

RETIRED 25305116.38 23561244.49

SELF-EMPLOYED 672393.40 1640252.54It can be easier to look at this data graphically as a bar plot ("barh" means horizontal bar plot; see Total donations by party for top occupations):

In [220]: over_2mm.plot(kind="barh")

You might be interested in the top donor occupations or top companies that donated to Obama and Romney. To do this, you can group by candidate name and use a variant of the top method from earlier in the chapter:

def get_top_amounts(group, key, n=5):

totals = group.groupby(key)["contb_receipt_amt"].sum()

return totals.nlargest(n)Then aggregate by occupation and employer:

In [222]: grouped = fec_mrbo.groupby("cand_nm")

In [223]: grouped.apply(get_top_amounts, "contbr_occupation", n=7)

Out[223]:

cand_nm contbr_occupation

Obama, Barack RETIRED 25305116.38

ATTORNEY 11141982.97

INFORMATION REQUESTED 4866973.96

HOMEMAKER 4248875.80

PHYSICIAN 3735124.94

LAWYER 3160478.87

CONSULTANT 2459912.71

Romney, Mitt RETIRED 11508473.59

INFORMATION REQUESTED PER BEST EFFORTS 11396894.84

HOMEMAKER 8147446.22

ATTORNEY 5364718.82

PRESIDENT 2491244.89

EXECUTIVE 2300947.03

C.E.O. 1968386.11

Name: contb_receipt_amt, dtype: float64

In [224]: grouped.apply(get_top_amounts, "contbr_employer", n=10)

Out[224]:

cand_nm contbr_employer

Obama, Barack RETIRED 22694358.85

SELF-EMPLOYED 17080985.96

NOT EMPLOYED 8586308.70

INFORMATION REQUESTED 5053480.37

HOMEMAKER 2605408.54

SELF 1076531.20

SELF EMPLOYED 469290.00

STUDENT 318831.45

VOLUNTEER 257104.00

MICROSOFT 215585.36

Romney, Mitt INFORMATION REQUESTED PER BEST EFFORTS 12059527.24

RETIRED 11506225.71

HOMEMAKER 8147196.22

SELF-EMPLOYED 7409860.98

STUDENT 496490.94

CREDIT SUISSE 281150.00

MORGAN STANLEY 267266.00

GOLDMAN SACH & CO. 238250.00

BARCLAYS CAPITAL 162750.00

H.I.G. CAPITAL 139500.00

Name: contb_receipt_amt, dtype: float64Bucketing Donation Amounts

A useful way to analyze this data is to use the cut function to discretize the contributor amounts into buckets by contribution size:

In [225]: bins = np.array([0, 1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000,

.....: 100_000, 1_000_000, 10_000_000])

In [226]: labels = pd.cut(fec_mrbo["contb_receipt_amt"], bins)

In [227]: labels

Out[227]:

411 (10, 100]

412 (100, 1000]

413 (100, 1000]

414 (10, 100]

415 (10, 100]

...

701381 (10, 100]

701382 (100, 1000]

701383 (1, 10]

701384 (10, 100]

701385 (100, 1000]

Name: contb_receipt_amt, Length: 694282, dtype: category

Categories (8, interval[int64, right]): [(0, 1] < (1, 10] < (10, 100] < (100, 100

0] <

(1000, 10000] < (10000, 100000] < (10000

0, 1000000] <

(1000000, 10000000]]We can then group the data for Obama and Romney by name and bin label to get a histogram by donation size:

In [228]: grouped = fec_mrbo.groupby(["cand_nm", labels])

In [229]: grouped.size().unstack(level=0)

Out[229]:

cand_nm Obama, Barack Romney, Mitt

contb_receipt_amt

(0, 1] 493 77

(1, 10] 40070 3681

(10, 100] 372280 31853

(100, 1000] 153991 43357

(1000, 10000] 22284 26186

(10000, 100000] 2 1

(100000, 1000000] 3 0

(1000000, 10000000] 4 0This data shows that Obama received a significantly larger number of small donations than Romney. You can also sum the contribution amounts and normalize within buckets to visualize the percentage of total donations of each size by candidate (Percentage of total donations received by candidates for each donation size shows the resulting plot):

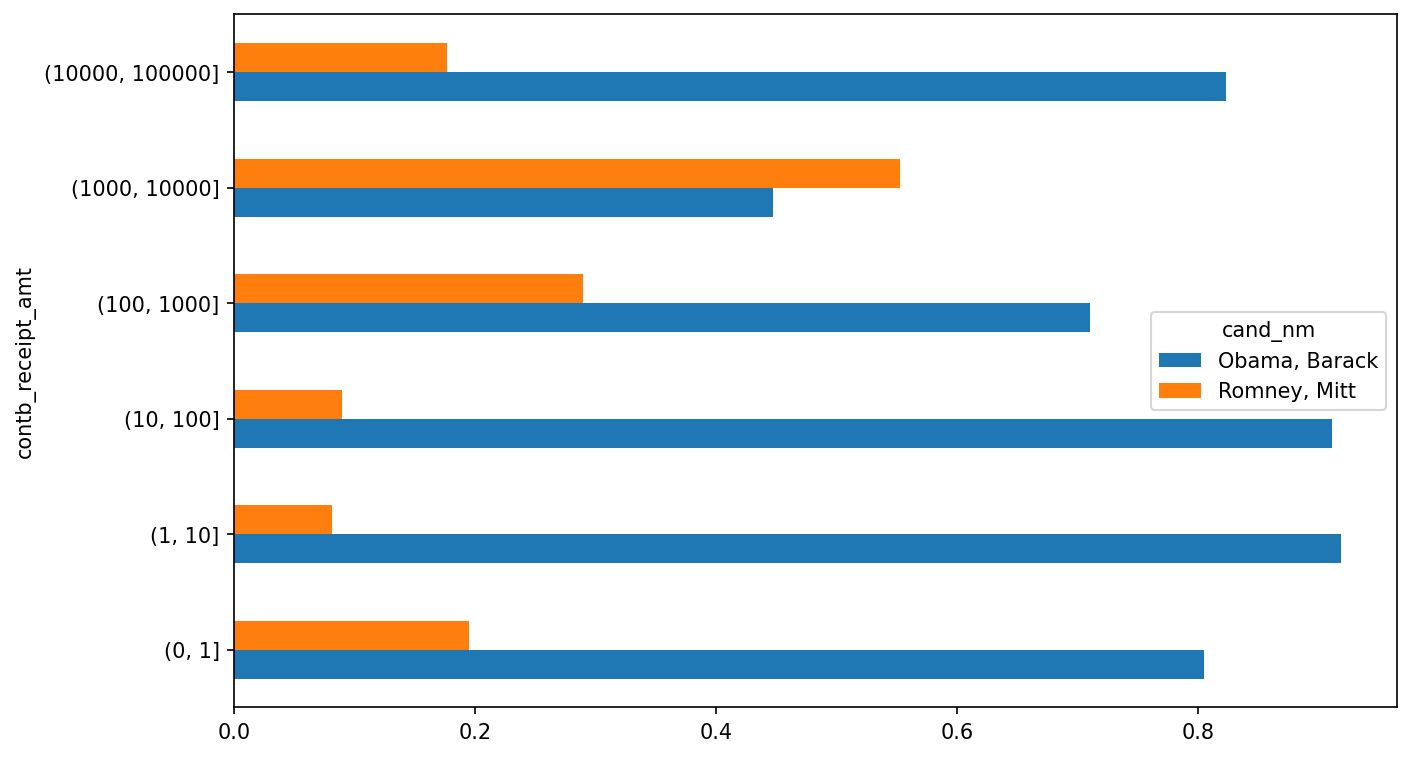

In [231]: bucket_sums = grouped["contb_receipt_amt"].sum().unstack(level=0)

In [232]: normed_sums = bucket_sums.div(bucket_sums.sum(axis="columns"),

.....: axis="index")

In [233]: normed_sums

Out[233]:

cand_nm Obama, Barack Romney, Mitt

contb_receipt_amt

(0, 1] 0.805182 0.194818

(1, 10] 0.918767 0.081233

(10, 100] 0.910769 0.089231

(100, 1000] 0.710176 0.289824

(1000, 10000] 0.447326 0.552674

(10000, 100000] 0.823120 0.176880

(100000, 1000000] 1.000000 0.000000

(1000000, 10000000] 1.000000 0.000000

In [234]: normed_sums[:-2].plot(kind="barh")

I excluded the two largest bins, as these are not donations by individuals.

This analysis can be refined and improved in many ways. For example, you could aggregate donations by donor name and zip code to adjust for donors who gave many small amounts versus one or more large donations. I encourage you to explore the dataset yourself.

Donation Statistics by State

We can start by aggregating the data by candidate and state:

In [235]: grouped = fec_mrbo.groupby(["cand_nm", "contbr_st"])

In [236]: totals = grouped["contb_receipt_amt"].sum().unstack(level=0).fillna(0)

In [237]: totals = totals[totals.sum(axis="columns") > 100000]

In [238]: totals.head(10)

Out[238]:

cand_nm Obama, Barack Romney, Mitt

contbr_st

AK 281840.15 86204.24

AL 543123.48 527303.51

AR 359247.28 105556.00

AZ 1506476.98 1888436.23

CA 23824984.24 11237636.60

CO 2132429.49 1506714.12

CT 2068291.26 3499475.45

DC 4373538.80 1025137.50

DE 336669.14 82712.00

FL 7318178.58 8338458.81If you divide each row by the total contribution amount, you get the relative percentage of total donations by state for each candidate:

In [239]: percent = totals.div(totals.sum(axis="columns"), axis="index")

In [240]: percent.head(10)

Out[240]:

cand_nm Obama, Barack Romney, Mitt

contbr_st

AK 0.765778 0.234222

AL 0.507390 0.492610

AR 0.772902 0.227098

AZ 0.443745 0.556255

CA 0.679498 0.320502

CO 0.585970 0.414030

CT 0.371476 0.628524

DC 0.810113 0.189887

DE 0.802776 0.197224

FL 0.467417 0.53258313.6 Conclusion

We've reached the end of this book. I have included some additional content you may find useful in the appendixes.

In the 10 years since the first edition of this book was published, Python has become a popular and widespread language for data analysis. The programming skills you have developed here will stay relevant for a long time into the future. I hope the programming tools and libraries we've explored will serve you well.

This makes the simplifying assumption that Gary Johnson is a Republican even though he later became the Libertarian party candidate.↩︎