3 Built-In Data Structures, Functions, and Files

This chapter discusses capabilities built into the Python language that will be used ubiquitously throughout the book. While add-on libraries like pandas and NumPy add advanced computational functionality for larger datasets, they are designed to be used together with Python's built-in data manipulation tools.

We'll start with Python's workhorse data structures: tuples, lists, dictionaries, and sets. Then, we'll discuss creating your own reusable Python functions. Finally, we'll look at the mechanics of Python file objects and interacting with your local hard drive.

3.1 Data Structures and Sequences

Python’s data structures are simple but powerful. Mastering their use is a critical part of becoming a proficient Python programmer. We start with tuple, list, and dictionary, which are some of the most frequently used sequence types.

Tuple

A tuple is a fixed-length, immutable sequence of Python objects which, once assigned, cannot be changed. The easiest way to create one is with a comma-separated sequence of values wrapped in parentheses:

In [2]: tup = (4, 5, 6)

In [3]: tup

Out[3]: (4, 5, 6)In many contexts, the parentheses can be omitted, so here we could also have written:

In [4]: tup = 4, 5, 6

In [5]: tup

Out[5]: (4, 5, 6)You can convert any sequence or iterator to a tuple by invoking tuple:

In [6]: tuple([4, 0, 2])

Out[6]: (4, 0, 2)

In [7]: tup = tuple('string')

In [8]: tup

Out[8]: ('s', 't', 'r', 'i', 'n', 'g')Elements can be accessed with square brackets [] as with most other sequence types. As in C, C++, Java, and many other languages, sequences are 0-indexed in Python:

In [9]: tup[0]

Out[9]: 's'When you're defining tuples within more complicated expressions, it’s often necessary to enclose the values in parentheses, as in this example of creating a tuple of tuples:

In [10]: nested_tup = (4, 5, 6), (7, 8)

In [11]: nested_tup

Out[11]: ((4, 5, 6), (7, 8))

In [12]: nested_tup[0]

Out[12]: (4, 5, 6)

In [13]: nested_tup[1]

Out[13]: (7, 8)While the objects stored in a tuple may be mutable themselves, once the tuple is created it’s not possible to modify which object is stored in each slot:

In [14]: tup = tuple(['foo', [1, 2], True])

In [15]: tup[2] = False

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-15-b89d0c4ae599> in <module>

----> 1 tup[2] = False

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentIf an object inside a tuple is mutable, such as a list, you can modify it in place:

In [16]: tup[1].append(3)

In [17]: tup

Out[17]: ('foo', [1, 2, 3], True)You can concatenate tuples using the + operator to produce longer tuples:

In [18]: (4, None, 'foo') + (6, 0) + ('bar',)

Out[18]: (4, None, 'foo', 6, 0, 'bar')Multiplying a tuple by an integer, as with lists, has the effect of concatenating that many copies of the tuple:

In [19]: ('foo', 'bar') * 4

Out[19]: ('foo', 'bar', 'foo', 'bar', 'foo', 'bar', 'foo', 'bar')Note that the objects themselves are not copied, only the references to them.

Unpacking tuples

If you try to assign to a tuple-like expression of variables, Python will attempt to unpack the value on the righthand side of the equals sign:

In [20]: tup = (4, 5, 6)

In [21]: a, b, c = tup

In [22]: b

Out[22]: 5Even sequences with nested tuples can be unpacked:

In [23]: tup = 4, 5, (6, 7)

In [24]: a, b, (c, d) = tup

In [25]: d

Out[25]: 7Using this functionality you can easily swap variable names, a task that in many languages might look like:

tmp = a

a = b

b = tmpBut, in Python, the swap can be done like this:

In [26]: a, b = 1, 2

In [27]: a

Out[27]: 1

In [28]: b

Out[28]: 2

In [29]: b, a = a, b

In [30]: a

Out[30]: 2

In [31]: b

Out[31]: 1A common use of variable unpacking is iterating over sequences of tuples or lists:

In [32]: seq = [(1, 2, 3), (4, 5, 6), (7, 8, 9)]

In [33]: for a, b, c in seq:

....: print(f'a={a}, b={b}, c={c}')

a=1, b=2, c=3

a=4, b=5, c=6

a=7, b=8, c=9Another common use is returning multiple values from a function. I'll cover this in more detail later.

There are some situations where you may want to "pluck" a few elements from the beginning of a tuple. There is a special syntax that can do this, *rest, which is also used in function signatures to capture an arbitrarily long list of positional arguments:

In [34]: values = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

In [35]: a, b, *rest = values

In [36]: a

Out[36]: 1

In [37]: b

Out[37]: 2

In [38]: rest

Out[38]: [3, 4, 5]This rest bit is sometimes something you want to discard; there is nothing special about the rest name. As a matter of convention, many Python programmers will use the underscore (_) for unwanted variables:

In [39]: a, b, *_ = valuesTuple methods

Since the size and contents of a tuple cannot be modified, it is very light on instance methods. A particularly useful one (also available on lists) is count, which counts the number of occurrences of a value:

In [40]: a = (1, 2, 2, 2, 3, 4, 2)

In [41]: a.count(2)

Out[41]: 4List

In contrast with tuples, lists are variable length and their contents can be modified in place. Lists are mutable. You can define them using square brackets [] or using the list type function:

In [42]: a_list = [2, 3, 7, None]

In [43]: tup = ("foo", "bar", "baz")

In [44]: b_list = list(tup)

In [45]: b_list

Out[45]: ['foo', 'bar', 'baz']

In [46]: b_list[1] = "peekaboo"

In [47]: b_list

Out[47]: ['foo', 'peekaboo', 'baz']Lists and tuples are semantically similar (though tuples cannot be modified) and can be used interchangeably in many functions.

The list built-in function is frequently used in data processing as a way to materialize an iterator or generator expression:

In [48]: gen = range(10)

In [49]: gen

Out[49]: range(0, 10)

In [50]: list(gen)

Out[50]: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]Adding and removing elements

Elements can be appended to the end of the list with the append method:

In [51]: b_list.append("dwarf")

In [52]: b_list

Out[52]: ['foo', 'peekaboo', 'baz', 'dwarf']Using insert you can insert an element at a specific location in the list:

In [53]: b_list.insert(1, "red")

In [54]: b_list

Out[54]: ['foo', 'red', 'peekaboo', 'baz', 'dwarf']The insertion index must be between 0 and the length of the list, inclusive.

insert is computationally expensive compared with append, because references to subsequent elements have to be shifted internally to make room for the new element. If you need to insert elements at both the beginning and end of a sequence, you may wish to explore collections.deque, a double-ended queue, which is optimized for this purpose and found in the Python Standard Library.

The inverse operation to insert is pop, which removes and returns an element at a particular index:

In [55]: b_list.pop(2)

Out[55]: 'peekaboo'

In [56]: b_list

Out[56]: ['foo', 'red', 'baz', 'dwarf']Elements can be removed by value with remove, which locates the first such value and removes it from the list:

In [57]: b_list.append("foo")

In [58]: b_list

Out[58]: ['foo', 'red', 'baz', 'dwarf', 'foo']

In [59]: b_list.remove("foo")

In [60]: b_list

Out[60]: ['red', 'baz', 'dwarf', 'foo']If performance is not a concern, by using append and remove, you can use a Python list as a set-like data structure (although Python has actual set objects, discussed later).

Check if a list contains a value using the in keyword:

In [61]: "dwarf" in b_list

Out[61]: TrueThe keyword not can be used to negate in:

In [62]: "dwarf" not in b_list

Out[62]: FalseChecking whether a list contains a value is a lot slower than doing so with dictionaries and sets (to be introduced shortly), as Python makes a linear scan across the values of the list, whereas it can check the others (based on hash tables) in constant time.

Concatenating and combining lists

Similar to tuples, adding two lists together with + concatenates them:

In [63]: [4, None, "foo"] + [7, 8, (2, 3)]

Out[63]: [4, None, 'foo', 7, 8, (2, 3)]If you have a list already defined, you can append multiple elements to it using the extend method:

In [64]: x = [4, None, "foo"]

In [65]: x.extend([7, 8, (2, 3)])

In [66]: x

Out[66]: [4, None, 'foo', 7, 8, (2, 3)]Note that list concatenation by addition is a comparatively expensive operation since a new list must be created and the objects copied over. Using extend to append elements to an existing list, especially if you are building up a large list, is usually preferable. Thus:

everything = []

for chunk in list_of_lists:

everything.extend(chunk)is faster than the concatenative alternative:

everything = []

for chunk in list_of_lists:

everything = everything + chunkSorting

You can sort a list in place (without creating a new object) by calling its sort function:

In [67]: a = [7, 2, 5, 1, 3]

In [68]: a.sort()

In [69]: a

Out[69]: [1, 2, 3, 5, 7]sort has a few options that will occasionally come in handy. One is the ability to pass a secondary sort key—that is, a function that produces a value to use to sort the objects. For example, we could sort a collection of strings by their lengths:

In [70]: b = ["saw", "small", "He", "foxes", "six"]

In [71]: b.sort(key=len)

In [72]: b

Out[72]: ['He', 'saw', 'six', 'small', 'foxes']Soon, we'll look at the sorted function, which can produce a sorted copy of a general sequence.

Slicing

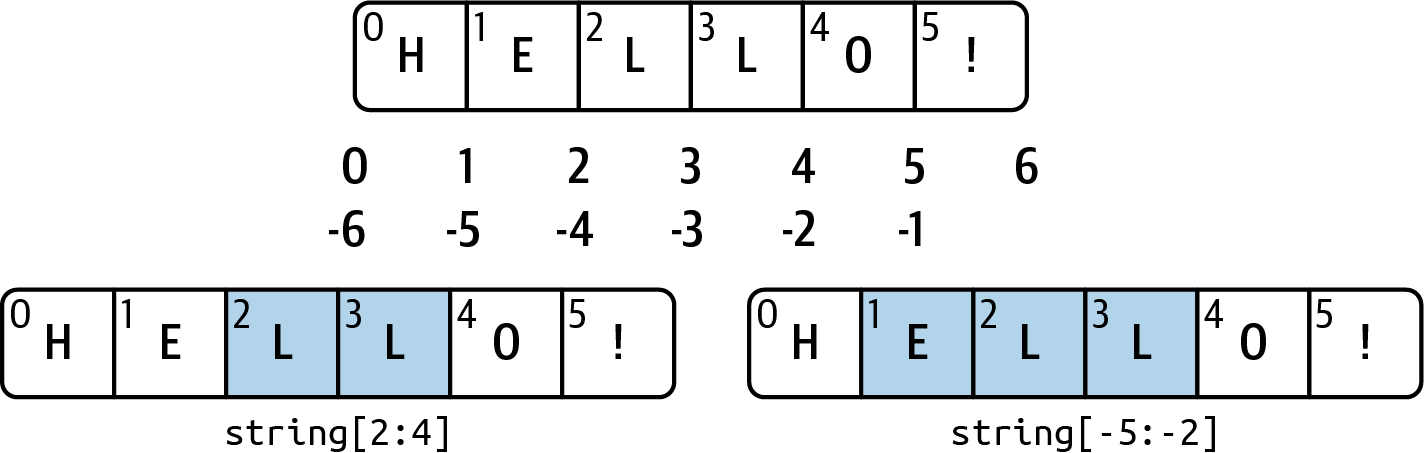

You can select sections of most sequence types by using slice notation, which in its basic form consists of start:stop passed to the indexing operator []:

In [73]: seq = [7, 2, 3, 7, 5, 6, 0, 1]

In [74]: seq[1:5]

Out[74]: [2, 3, 7, 5]Slices can also be assigned with a sequence:

In [75]: seq[3:5] = [6, 3]

In [76]: seq

Out[76]: [7, 2, 3, 6, 3, 6, 0, 1]While the element at the start index is included, the stop index is not included, so that the number of elements in the result is stop - start.

Either the start or stop can be omitted, in which case they default to the start of the sequence and the end of the sequence, respectively:

In [77]: seq[:5]

Out[77]: [7, 2, 3, 6, 3]

In [78]: seq[3:]

Out[78]: [6, 3, 6, 0, 1]Negative indices slice the sequence relative to the end:

In [79]: seq[-4:]

Out[79]: [3, 6, 0, 1]

In [80]: seq[-6:-2]

Out[80]: [3, 6, 3, 6]Slicing semantics takes a bit of getting used to, especially if you’re coming from R or MATLAB. See Figure 3.1 for a helpful illustration of slicing with positive and negative integers. In the figure, the indices are shown at the "bin edges" to help show where the slice selections start and stop using positive or negative indices.

A step can also be used after a second colon to, say, take every other element:

In [81]: seq[::2]

Out[81]: [7, 3, 3, 0]A clever use of this is to pass -1, which has the useful effect of reversing a list or tuple:

In [82]: seq[::-1]

Out[82]: [1, 0, 6, 3, 6, 3, 2, 7]Dictionary

The dictionary or dict may be the most important built-in Python data structure. In other programming languages, dictionaries are sometimes called hash maps or associative arrays. A dictionary stores a collection of key-value pairs, where key and value are Python objects. Each key is associated with a value so that a value can be conveniently retrieved, inserted, modified, or deleted given a particular key. One approach for creating a dictionary is to use curly braces {} and colons to separate keys and values:

In [83]: empty_dict = {}

In [84]: d1 = {"a": "some value", "b": [1, 2, 3, 4]}

In [85]: d1

Out[85]: {'a': 'some value', 'b': [1, 2, 3, 4]}You can access, insert, or set elements using the same syntax as for accessing elements of a list or tuple:

In [86]: d1[7] = "an integer"

In [87]: d1

Out[87]: {'a': 'some value', 'b': [1, 2, 3, 4], 7: 'an integer'}

In [88]: d1["b"]

Out[88]: [1, 2, 3, 4]You can check if a dictionary contains a key using the same syntax used for checking whether a list or tuple contains a value:

In [89]: "b" in d1

Out[89]: TrueYou can delete values using either the del keyword or the pop method (which simultaneously returns the value and deletes the key):

In [90]: d1[5] = "some value"

In [91]: d1

Out[91]:

{'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer',

5: 'some value'}

In [92]: d1["dummy"] = "another value"

In [93]: d1

Out[93]:

{'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer',

5: 'some value',

'dummy': 'another value'}

In [94]: del d1[5]

In [95]: d1

Out[95]:

{'a': 'some value',

'b': [1, 2, 3, 4],

7: 'an integer',

'dummy': 'another value'}

In [96]: ret = d1.pop("dummy")

In [97]: ret

Out[97]: 'another value'

In [98]: d1

Out[98]: {'a': 'some value', 'b': [1, 2, 3, 4], 7: 'an integer'}The keys and values method gives you iterators of the dictionary's keys and values, respectively. The order of the keys depends on the order of their insertion, and these functions output the keys and values in the same respective order:

In [99]: list(d1.keys())

Out[99]: ['a', 'b', 7]

In [100]: list(d1.values())

Out[100]: ['some value', [1, 2, 3, 4], 'an integer']If you need to iterate over both the keys and values, you can use the items method to iterate over the keys and values as 2-tuples:

In [101]: list(d1.items())

Out[101]: [('a', 'some value'), ('b', [1, 2, 3, 4]), (7, 'an integer')]You can merge one dictionary into another using the update method:

In [102]: d1.update({"b": "foo", "c": 12})

In [103]: d1

Out[103]: {'a': 'some value', 'b': 'foo', 7: 'an integer', 'c': 12}The update method changes dictionaries in place, so any existing keys in the data passed to update will have their old values discarded.

Creating dictionaries from sequences

It’s common to occasionally end up with two sequences that you want to pair up element-wise in a dictionary. As a first cut, you might write code like this:

mapping = {}

for key, value in zip(key_list, value_list):

mapping[key] = valueSince a dictionary is essentially a collection of 2-tuples, the dict function accepts a list of 2-tuples:

In [104]: tuples = zip(range(5), reversed(range(5)))

In [105]: tuples

Out[105]: <zip at 0x17d604d00>

In [106]: mapping = dict(tuples)

In [107]: mapping

Out[107]: {0: 4, 1: 3, 2: 2, 3: 1, 4: 0}Later we’ll talk about dictionary comprehensions, which are another way to construct dictionaries.

Default values

It’s common to have logic like:

if key in some_dict:

value = some_dict[key]

else:

value = default_valueThus, the dictionary methods get and pop can take a default value to be returned, so that the above if-else block can be written simply as:

value = some_dict.get(key, default_value)get by default will return None if the key is not present, while pop will raise an exception. With setting values, it may be that the values in a dictionary are another kind of collection, like a list. For example, you could imagine categorizing a list of words by their first letters as a dictionary of lists:

In [108]: words = ["apple", "bat", "bar", "atom", "book"]

In [109]: by_letter = {}

In [110]: for word in words:

.....: letter = word[0]

.....: if letter not in by_letter:

.....: by_letter[letter] = [word]

.....: else:

.....: by_letter[letter].append(word)

.....:

In [111]: by_letter

Out[111]: {'a': ['apple', 'atom'], 'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']}The setdefault dictionary method can be used to simplify this workflow. The preceding for loop can be rewritten as:

In [112]: by_letter = {}

In [113]: for word in words:

.....: letter = word[0]

.....: by_letter.setdefault(letter, []).append(word)

.....:

In [114]: by_letter

Out[114]: {'a': ['apple', 'atom'], 'b': ['bat', 'bar', 'book']}The built-in collections module has a useful class, defaultdict, which makes this even easier. To create one, you pass a type or function for generating the default value for each slot in the dictionary:

In [115]: from collections import defaultdict

In [116]: by_letter = defaultdict(list)

In [117]: for word in words:

.....: by_letter[word[0]].append(word)Valid dictionary key types

While the values of a dictionary can be any Python object, the keys generally have to be immutable objects like scalar types (int, float, string) or tuples (all the objects in the tuple need to be immutable, too). The technical term here is hashability. You can check whether an object is hashable (can be used as a key in a dictionary) with the hash function:

In [118]: hash("string")

Out[118]: 4022908869268713487

In [119]: hash((1, 2, (2, 3)))

Out[119]: -9209053662355515447

In [120]: hash((1, 2, [2, 3])) # fails because lists are mutable

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-120-473c35a62c0b> in <module>

----> 1 hash((1, 2, [2, 3])) # fails because lists are mutable

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'The hash values you see when using the hash function in general will depend on the Python version you are using.

To use a list as a key, one option is to convert it to a tuple, which can be hashed as long as its elements also can be:

In [121]: d = {}

In [122]: d[tuple([1, 2, 3])] = 5

In [123]: d

Out[123]: {(1, 2, 3): 5}Set

A set is an unordered collection of unique elements. A set can be created in two ways: via the set function or via a set literal with curly braces:

In [124]: set([2, 2, 2, 1, 3, 3])

Out[124]: {1, 2, 3}

In [125]: {2, 2, 2, 1, 3, 3}

Out[125]: {1, 2, 3}Sets support mathematical set operations like union, intersection, difference, and symmetric difference. Consider these two example sets:

In [126]: a = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

In [127]: b = {3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}The union of these two sets is the set of distinct elements occurring in either set. This can be computed with either the union method or the | binary operator:

In [128]: a.union(b)

Out[128]: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

In [129]: a | b

Out[129]: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}The intersection contains the elements occurring in both sets. The & operator or the intersection method can be used:

In [130]: a.intersection(b)

Out[130]: {3, 4, 5}

In [131]: a & b

Out[131]: {3, 4, 5}See Table 3.1 for a list of commonly used set methods.

| Function | Alternative syntax | Description |

|---|---|---|

a.add(x) |

N/A | Add element x to set a |

a.clear() |

N/A | Reset set a to an empty state, discarding all of its elements |

a.remove(x) |

N/A | Remove element x from set a |

a.pop() |

N/A | Remove an arbitrary element from set a, raising KeyError if the set is empty |

a.union(b) |

a | b |

All of the unique elements in a and b |

a.update(b) |

a |= b |

Set the contents of a to be the union of the elements in a and b |

a.intersection(b) |

a & b |

All of the elements in both a and b |

a.intersection_update(b) |

a &= b |

Set the contents of a to be the intersection of the elements in a and b |

a.difference(b) |

a - b |

The elements in a that are not in b |

a.difference_update(b) |

a -= b |

Set a to the elements in a that are not in b |

a.symmetric_difference(b) |

a ^ b |

All of the elements in either a or b but not both |

a.symmetric_difference_update(b) |

a ^= b |

Set a to contain the elements in either a or b but not both |

a.issubset(b) |

<= |

True if the elements of a are all contained in b |

a.issuperset(b) |

>= |

True if the elements of b are all contained in a |

a.isdisjoint(b) |

N/A | True if a and b have no elements in common |

If you pass an input that is not a set to methods like union and intersection, Python will convert the input to a set before executing the operation. When using the binary operators, both objects must already be sets.

All of the logical set operations have in-place counterparts, which enable you to replace the contents of the set on the left side of the operation with the result. For very large sets, this may be more efficient:

In [132]: c = a.copy()

In [133]: c |= b

In [134]: c

Out[134]: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

In [135]: d = a.copy()

In [136]: d &= b

In [137]: d

Out[137]: {3, 4, 5}Like dictionary keys, set elements generally must be immutable, and they must be hashable (which means that calling hash on a value does not raise an exception). In order to store list-like elements (or other mutable sequences) in a set, you can convert them to tuples:

In [138]: my_data = [1, 2, 3, 4]

In [139]: my_set = {tuple(my_data)}

In [140]: my_set

Out[140]: {(1, 2, 3, 4)}You can also check if a set is a subset of (is contained in) or a superset of (contains all elements of) another set:

In [141]: a_set = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

In [142]: {1, 2, 3}.issubset(a_set)

Out[142]: True

In [143]: a_set.issuperset({1, 2, 3})

Out[143]: TrueSets are equal if and only if their contents are equal:

In [144]: {1, 2, 3} == {3, 2, 1}

Out[144]: TrueBuilt-In Sequence Functions

Python has a handful of useful sequence functions that you should familiarize yourself with and use at any opportunity.

enumerate

It’s common when iterating over a sequence to want to keep track of the index of the current item. A do-it-yourself approach would look like:

index = 0

for value in collection:

# do something with value

index += 1Since this is so common, Python has a built-in function, enumerate, which returns a sequence of (i, value) tuples:

for index, value in enumerate(collection):

# do something with valuesorted

The sorted function returns a new sorted list from the elements of any sequence:

In [145]: sorted([7, 1, 2, 6, 0, 3, 2])

Out[145]: [0, 1, 2, 2, 3, 6, 7]

In [146]: sorted("horse race")

Out[146]: [' ', 'a', 'c', 'e', 'e', 'h', 'o', 'r', 'r', 's']The sorted function accepts the same arguments as the sort method on lists.

zip

zip “pairs” up the elements of a number of lists, tuples, or other sequences to create a list of tuples:

In [147]: seq1 = ["foo", "bar", "baz"]

In [148]: seq2 = ["one", "two", "three"]

In [149]: zipped = zip(seq1, seq2)

In [150]: list(zipped)

Out[150]: [('foo', 'one'), ('bar', 'two'), ('baz', 'three')]zip can take an arbitrary number of sequences, and the number of elements it produces is determined by the shortest sequence:

In [151]: seq3 = [False, True]

In [152]: list(zip(seq1, seq2, seq3))

Out[152]: [('foo', 'one', False), ('bar', 'two', True)]A common use of zip is simultaneously iterating over multiple sequences, possibly also combined with enumerate:

In [153]: for index, (a, b) in enumerate(zip(seq1, seq2)):

.....: print(f"{index}: {a}, {b}")

.....:

0: foo, one

1: bar, two

2: baz, threereversed

reversed iterates over the elements of a sequence in reverse order:

In [154]: list(reversed(range(10)))

Out[154]: [9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]Keep in mind that reversed is a generator (to be discussed in some more detail later), so it does not create the reversed sequence until materialized (e.g., with list or a for loop).

List, Set, and Dictionary Comprehensions

List comprehensions are a convenient and widely used Python language feature. They allow you to concisely form a new list by filtering the elements of a collection, transforming the elements passing the filter into one concise expression. They take the basic form:

[expr for value in collection if condition]This is equivalent to the following for loop:

result = []

for value in collection:

if condition:

result.append(expr)The filter condition can be omitted, leaving only the expression. For example, given a list of strings, we could filter out strings with length 2 or less and convert them to uppercase like this:

In [155]: strings = ["a", "as", "bat", "car", "dove", "python"]

In [156]: [x.upper() for x in strings if len(x) > 2]

Out[156]: ['BAT', 'CAR', 'DOVE', 'PYTHON']Set and dictionary comprehensions are a natural extension, producing sets and dictionaries in an idiomatically similar way instead of lists.

A dictionary comprehension looks like this:

dict_comp = {key-expr: value-expr for value in collection

if condition}A set comprehension looks like the equivalent list comprehension except with curly braces instead of square brackets:

set_comp = {expr for value in collection if condition}Like list comprehensions, set and dictionary comprehensions are mostly conveniences, but they similarly can make code both easier to write and read. Consider the list of strings from before. Suppose we wanted a set containing just the lengths of the strings contained in the collection; we could easily compute this using a set comprehension:

In [157]: unique_lengths = {len(x) for x in strings}

In [158]: unique_lengths

Out[158]: {1, 2, 3, 4, 6}We could also express this more functionally using the map function, introduced shortly:

In [159]: set(map(len, strings))

Out[159]: {1, 2, 3, 4, 6}As a simple dictionary comprehension example, we could create a lookup map of these strings for their locations in the list:

In [160]: loc_mapping = {value: index for index, value in enumerate(strings)}

In [161]: loc_mapping

Out[161]: {'a': 0, 'as': 1, 'bat': 2, 'car': 3, 'dove': 4, 'python': 5}Nested list comprehensions

Suppose we have a list of lists containing some English and Spanish names:

In [162]: all_data = [["John", "Emily", "Michael", "Mary", "Steven"],

.....: ["Maria", "Juan", "Javier", "Natalia", "Pilar"]]Suppose we wanted to get a single list containing all names with two or more a’s in them. We could certainly do this with a simple for loop:

In [163]: names_of_interest = []

In [164]: for names in all_data:

.....: enough_as = [name for name in names if name.count("a") >= 2]

.....: names_of_interest.extend(enough_as)

.....:

In [165]: names_of_interest

Out[165]: ['Maria', 'Natalia']You can actually wrap this whole operation up in a single nested list comprehension, which will look like:

In [166]: result = [name for names in all_data for name in names

.....: if name.count("a") >= 2]

In [167]: result

Out[167]: ['Maria', 'Natalia']At first, nested list comprehensions are a bit hard to wrap your head around. The for parts of the list comprehension are arranged according to the order of nesting, and any filter condition is put at the end as before. Here is another example where we “flatten” a list of tuples of integers into a simple list of integers:

In [168]: some_tuples = [(1, 2, 3), (4, 5, 6), (7, 8, 9)]

In [169]: flattened = [x for tup in some_tuples for x in tup]

In [170]: flattened

Out[170]: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]Keep in mind that the order of the for expressions would be the same if you wrote a nested for loop instead of a list comprehension:

flattened = []

for tup in some_tuples:

for x in tup:

flattened.append(x)You can have arbitrarily many levels of nesting, though if you have more than two or three levels of nesting, you should probably start to question whether this makes sense from a code readability standpoint. It’s important to distinguish the syntax just shown from a list comprehension inside a list comprehension, which is also perfectly valid:

In [172]: [[x for x in tup] for tup in some_tuples]

Out[172]: [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]This produces a list of lists, rather than a flattened list of all of the inner elements.

3.2 Functions

Functions are the primary and most important method of code organization and reuse in Python. As a rule of thumb, if you anticipate needing to repeat the same or very similar code more than once, it may be worth writing a reusable function. Functions can also help make your code more readable by giving a name to a group of Python statements.

Functions are declared with the def keyword. A function contains a block of code with an optional use of the return keyword:

In [173]: def my_function(x, y):

.....: return x + yWhen a line with return is reached, the value or expression after return is sent to the context where the function was called, for example:

In [174]: my_function(1, 2)

Out[174]: 3

In [175]: result = my_function(1, 2)

In [176]: result

Out[176]: 3There is no issue with having multiple return statements. If Python reaches the end of a function without encountering a return statement, None is returned automatically. For example:

In [177]: def function_without_return(x):

.....: print(x)

In [178]: result = function_without_return("hello!")

hello!

In [179]: print(result)

NoneEach function can have positional arguments and keyword arguments. Keyword arguments are most commonly used to specify default values or optional arguments. Here we will define a function with an optional z argument with the default value 1.5:

def my_function2(x, y, z=1.5):

if z > 1:

return z * (x + y)

else:

return z / (x + y)While keyword arguments are optional, all positional arguments must be specified when calling a function.

You can pass values to the z argument with or without the keyword provided, though using the keyword is encouraged:

In [181]: my_function2(5, 6, z=0.7)

Out[181]: 0.06363636363636363

In [182]: my_function2(3.14, 7, 3.5)

Out[182]: 35.49

In [183]: my_function2(10, 20)

Out[183]: 45.0The main restriction on function arguments is that the keyword arguments must follow the positional arguments (if any). You can specify keyword arguments in any order. This frees you from having to remember the order in which the function arguments were specified. You need to remember only what their names are.

Namespaces, Scope, and Local Functions

Functions can access variables created inside the function as well as those outside the function in higher (or even global) scopes. An alternative and more descriptive name describing a variable scope in Python is a namespace. Any variables that are assigned within a function by default are assigned to the local namespace. The local namespace is created when the function is called and is immediately populated by the function’s arguments. After the function is finished, the local namespace is destroyed (with some exceptions that are outside the purview of this chapter). Consider the following function:

def func():

a = []

for i in range(5):

a.append(i)When func() is called, the empty list a is created, five elements are appended, and then a is destroyed when the function exits. Suppose instead we had declared a as follows:

In [184]: a = []

In [185]: def func():

.....: for i in range(5):

.....: a.append(i)Each call to func will modify list a:

In [186]: func()

In [187]: a

Out[187]: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

In [188]: func()

In [189]: a

Out[189]: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4]Assigning variables outside of the function's scope is possible, but those variables must be declared explicitly using either the global or nonlocal keywords:

In [190]: a = None

In [191]: def bind_a_variable():

.....: global a

.....: a = []

.....: bind_a_variable()

.....:

In [192]: print(a)

[]nonlocal allows a function to modify variables defined in a higher-level scope that is not global. Since its use is somewhat esoteric (I never use it in this book), I refer you to the Python documentation to learn more about it.

I generally discourage use of the global keyword. Typically, global variables are used to store some kind of state in a system. If you find yourself using a lot of them, it may indicate a need for object-oriented programming (using classes).

Returning Multiple Values

When I first programmed in Python after having programmed in Java and C++, one of my favorite features was the ability to return multiple values from a function with simple syntax. Here’s an example:

def f():

a = 5

b = 6

c = 7

return a, b, c

a, b, c = f()In data analysis and other scientific applications, you may find yourself doing this often. What’s happening here is that the function is actually just returning one object, a tuple, which is then being unpacked into the result variables. In the preceding example, we could have done this instead:

return_value = f()In this case, return_value would be a 3-tuple with the three returned variables. A potentially attractive alternative to returning multiple values like before might be to return a dictionary instead:

def f():

a = 5

b = 6

c = 7

return {"a" : a, "b" : b, "c" : c}This alternative technique can be useful depending on what you are trying to do.

Functions Are Objects

Since Python functions are objects, many constructs can be easily expressed that are difficult to do in other languages. Suppose we were doing some data cleaning and needed to apply a bunch of transformations to the following list of strings:

In [193]: states = [" Alabama ", "Georgia!", "Georgia", "georgia", "FlOrIda",

.....: "south carolina##", "West virginia?"]Anyone who has ever worked with user-submitted survey data has seen messy results like these. Lots of things need to happen to make this list of strings uniform and ready for analysis: stripping whitespace, removing punctuation symbols, and standardizing proper capitalization. One way to do this is to use built-in string methods along with the re standard library module for regular expressions:

import re

def clean_strings(strings):

result = []

for value in strings:

value = value.strip()

value = re.sub("[!#?]", "", value)

value = value.title()

result.append(value)

return resultThe result looks like this:

In [195]: clean_strings(states)

Out[195]:

['Alabama',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Florida',

'South Carolina',

'West Virginia']An alternative approach that you may find useful is to make a list of the operations you want to apply to a particular set of strings:

def remove_punctuation(value):

return re.sub("[!#?]", "", value)

clean_ops = [str.strip, remove_punctuation, str.title]

def clean_strings(strings, ops):

result = []

for value in strings:

for func in ops:

value = func(value)

result.append(value)

return resultThen we have the following:

In [197]: clean_strings(states, clean_ops)

Out[197]:

['Alabama',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Georgia',

'Florida',

'South Carolina',

'West Virginia']A more functional pattern like this enables you to easily modify how the strings are transformed at a very high level. The clean_strings function is also now more reusable and generic.

You can use functions as arguments to other functions like the built-in map function, which applies a function to a sequence of some kind:

In [198]: for x in map(remove_punctuation, states):

.....: print(x)

Alabama

Georgia

Georgia

georgia

FlOrIda

south carolina

West virginiamap can be used as an alternative to list comprehensions without any filter.

Anonymous (Lambda) Functions

Python has support for so-called anonymous or lambda functions, which are a way of writing functions consisting of a single statement, the result of which is the return value. They are defined with the lambda keyword, which has no meaning other than “we are declaring an anonymous function”:

In [199]: def short_function(x):

.....: return x * 2

In [200]: equiv_anon = lambda x: x * 2I usually refer to these as lambda functions in the rest of the book. They are especially convenient in data analysis because, as you’ll see, there are many cases where data transformation functions will take functions as arguments. It’s often less typing (and clearer) to pass a lambda function as opposed to writing a full-out function declaration or even assigning the lambda function to a local variable. Consider this example:

In [201]: def apply_to_list(some_list, f):

.....: return [f(x) for x in some_list]

In [202]: ints = [4, 0, 1, 5, 6]

In [203]: apply_to_list(ints, lambda x: x * 2)

Out[203]: [8, 0, 2, 10, 12]You could also have written [x * 2 for x in ints], but here we were able to succinctly pass a custom operator to the apply_to_list function.

As another example, suppose you wanted to sort a collection of strings by the number of distinct letters in each string:

In [204]: strings = ["foo", "card", "bar", "aaaa", "abab"]Here we could pass a lambda function to the list’s sort method:

In [205]: strings.sort(key=lambda x: len(set(x)))

In [206]: strings

Out[206]: ['aaaa', 'foo', 'abab', 'bar', 'card']Generators

Many objects in Python support iteration, such as over objects in a list or lines in a file. This is accomplished by means of the iterator protocol, a generic way to make objects iterable. For example, iterating over a dictionary yields the dictionary keys:

In [207]: some_dict = {"a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3}

In [208]: for key in some_dict:

.....: print(key)

a

b

cWhen you write for key in some_dict, the Python interpreter first attempts to create an iterator out of some_dict:

In [209]: dict_iterator = iter(some_dict)

In [210]: dict_iterator

Out[210]: <dict_keyiterator at 0x17d60e020>An iterator is any object that will yield objects to the Python interpreter when used in a context like a for loop. Most methods expecting a list or list-like object will also accept any iterable object. This includes built-in methods such as min, max, and sum, and type constructors like list and tuple:

In [211]: list(dict_iterator)

Out[211]: ['a', 'b', 'c']A generator is a convenient way, similar to writing a normal function, to construct a new iterable object. Whereas normal functions execute and return a single result at a time, generators can return a sequence of multiple values by pausing and resuming execution each time the generator is used. To create a generator, use the yield keyword instead of return in a function:

def squares(n=10):

print(f"Generating squares from 1 to {n ** 2}")

for i in range(1, n + 1):

yield i ** 2When you actually call the generator, no code is immediately executed:

In [213]: gen = squares()

In [214]: gen

Out[214]: <generator object squares at 0x17d5fea40>It is not until you request elements from the generator that it begins executing its code:

In [215]: for x in gen:

.....: print(x, end=" ")

Generating squares from 1 to 100

1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100Since generators produce output one element at a time versus an entire list all at once, it can help your program use less memory.

Generator expressions

Another way to make a generator is by using a generator expression. This is a generator analogue to list, dictionary, and set comprehensions. To create one, enclose what would otherwise be a list comprehension within parentheses instead of brackets:

In [216]: gen = (x ** 2 for x in range(100))

In [217]: gen

Out[217]: <generator object <genexpr> at 0x17d5feff0>This is equivalent to the following more verbose generator:

def _make_gen():

for x in range(100):

yield x ** 2

gen = _make_gen()Generator expressions can be used instead of list comprehensions as function arguments in some cases:

In [218]: sum(x ** 2 for x in range(100))

Out[218]: 328350

In [219]: dict((i, i ** 2) for i in range(5))

Out[219]: {0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16}Depending on the number of elements produced by the comprehension expression, the generator version can sometimes be meaningfully faster.

itertools module

The standard library itertools module has a collection of generators for many common data algorithms. For example, groupby takes any sequence and a function, grouping consecutive elements in the sequence by return value of the function. Here’s an example:

In [220]: import itertools

In [221]: def first_letter(x):

.....: return x[0]

In [222]: names = ["Alan", "Adam", "Wes", "Will", "Albert", "Steven"]

In [223]: for letter, names in itertools.groupby(names, first_letter):

.....: print(letter, list(names)) # names is a generator

A ['Alan', 'Adam']

W ['Wes', 'Will']

A ['Albert']

S ['Steven']See Table 3.2 for a list of a few other itertools functions I’ve frequently found helpful. You may like to check out the official Python documentation for more on this useful built-in utility module.

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

chain(*iterables) |

Generates a sequence by chaining iterators together. Once elements from the first iterator are exhausted, elements from the next iterator are returned, and so on. |

combinations(iterable, k) |

Generates a sequence of all possible k-tuples of elements in the iterable, ignoring order and without replacement (see also the companion function combinations_with_replacement). |

permutations(iterable, k) |

Generates a sequence of all possible k-tuples of elements in the iterable, respecting order. |

groupby(iterable[, keyfunc]) |

Generates (key, sub-iterator) for each unique key. |

product(*iterables, repeat=1) |

Generates the Cartesian product of the input iterables as tuples, similar to a nested for loop. |

Errors and Exception Handling

Handling Python errors or exceptions gracefully is an important part of building robust programs. In data analysis applications, many functions work only on certain kinds of input. As an example, Python’s float function is capable of casting a string to a floating-point number, but it fails with ValueError on improper inputs:

In [224]: float("1.2345")

Out[224]: 1.2345

In [225]: float("something")

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-225-5ccfe07933f4> in <module>

----> 1 float("something")

ValueError: could not convert string to float: 'something'Suppose we wanted a version of float that fails gracefully, returning the input argument. We can do this by writing a function that encloses the call to float in a try/except block (execute this code in IPython):

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except:

return xThe code in the except part of the block will only be executed if float(x) raises an exception:

In [227]: attempt_float("1.2345")

Out[227]: 1.2345

In [228]: attempt_float("something")

Out[228]: 'something'You might notice that float can raise exceptions other than ValueError:

In [229]: float((1, 2))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-229-82f777b0e564> in <module>

----> 1 float((1, 2))

TypeError: float() argument must be a string or a real number, not 'tuple'You might want to suppress only ValueError, since a TypeError (the input was not a string or numeric value) might indicate a legitimate bug in your program. To do that, write the exception type after except:

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except ValueError:

return xWe have then:

In [231]: attempt_float((1, 2))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-231-8b0026e9e6b7> in <module>

----> 1 attempt_float((1, 2))

<ipython-input-230-6209ddecd2b5> in attempt_float(x)

1 def attempt_float(x):

2 try:

----> 3 return float(x)

4 except ValueError:

5 return x

TypeError: float() argument must be a string or a real number, not 'tuple'You can catch multiple exception types by writing a tuple of exception types instead (the parentheses are required):

def attempt_float(x):

try:

return float(x)

except (TypeError, ValueError):

return xIn some cases, you may not want to suppress an exception, but you want some code to be executed regardless of whether or not the code in the try block succeeds. To do this, use finally:

f = open(path, mode="w")

try:

write_to_file(f)

finally:

f.close()Here, the file object f will always get closed. Similarly, you can have code that executes only if the try: block succeeds using else:

f = open(path, mode="w")

try:

write_to_file(f)

except:

print("Failed")

else:

print("Succeeded")

finally:

f.close()Exceptions in IPython

If an exception is raised while you are %run-ing a script or executing any statement, IPython will by default print a full call stack trace (traceback) with a few lines of context around the position at each point in the stack:

In [10]: %run examples/ipython_bug.py

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AssertionError Traceback (most recent call last)

/home/wesm/code/pydata-book/examples/ipython_bug.py in <module>()

13 throws_an_exception()

14

---> 15 calling_things()

/home/wesm/code/pydata-book/examples/ipython_bug.py in calling_things()

11 def calling_things():

12 works_fine()

---> 13 throws_an_exception()

14

15 calling_things()

/home/wesm/code/pydata-book/examples/ipython_bug.py in throws_an_exception()

7 a = 5

8 b = 6

----> 9 assert(a + b == 10)

10

11 def calling_things():

AssertionError:Having additional context by itself is a big advantage over the standard Python interpreter (which does not provide any additional context). You can control the amount of context shown using the %xmode magic command, from Plain (same as the standard Python interpreter) to Verbose (which inlines function argument values and more). As you will see later in Appendix B: More on the IPython System, you can step into the stack (using the %debug or %pdb magics) after an error has occurred for interactive postmortem debugging.

3.3 Files and the Operating System

Most of this book uses high-level tools like pandas.read_csv to read data files from disk into Python data structures. However, it’s important to understand the basics of how to work with files in Python. Fortunately, it’s relatively straightforward, which is one reason Python is so popular for text and file munging.

To open a file for reading or writing, use the built-in open function with either a relative or absolute file path and an optional file encoding:

In [233]: path = "examples/segismundo.txt"

In [234]: f = open(path, encoding="utf-8")Here, I pass encoding="utf-8" as a best practice because the default Unicode encoding for reading files varies from platform to platform.

By default, the file is opened in read-only mode "r". We can then treat the file object f like a list and iterate over the lines like so:

for line in f:

print(line)The lines come out of the file with the end-of-line (EOL) markers intact, so you’ll often see code to get an EOL-free list of lines in a file like:

In [235]: lines = [x.rstrip() for x in open(path, encoding="utf-8")]

In [236]: lines

Out[236]:

['Sueña el rico en su riqueza,',

'que más cuidados le ofrece;',

'',

'sueña el pobre que padece',

'su miseria y su pobreza;',

'',

'sueña el que a medrar empieza,',

'sueña el que afana y pretende,',

'sueña el que agravia y ofende,',

'',

'y en el mundo, en conclusión,',

'todos sueñan lo que son,',

'aunque ninguno lo entiende.',

'']When you use open to create file objects, it is recommended to close the file when you are finished with it. Closing the file releases its resources back to the operating system:

In [237]: f.close()One of the ways to make it easier to clean up open files is to use the with statement:

In [238]: with open(path, encoding="utf-8") as f:

.....: lines = [x.rstrip() for x in f]This will automatically close the file f when exiting the with block. Failing to ensure that files are closed will not cause problems in many small programs or scripts, but it can be an issue in programs that need to interact with a large number of files.

If we had typed f = open(path, "w"), a new file at examples/segismundo.txt would have been created (be careful!), overwriting any file in its place. There is also the "x" file mode, which creates a writable file but fails if the file path already exists. See Table 3.3 for a list of all valid file read/write modes.

| Mode | Description |

|---|---|

r |

Read-only mode |

w |

Write-only mode; creates a new file (erasing the data for any file with the same name) |

x |

Write-only mode; creates a new file but fails if the file path already exists |

a |

Append to existing file (creates the file if it does not already exist) |

r+ |

Read and write |

b |

Add to mode for binary files (i.e., "rb" or "wb") |

t |

Text mode for files (automatically decoding bytes to Unicode); this is the default if not specified |

For readable files, some of the most commonly used methods are read, seek, and tell. read returns a certain number of characters from the file. What constitutes a "character" is determined by the file encoding or simply raw bytes if the file is opened in binary mode:

In [239]: f1 = open(path)

In [240]: f1.read(10)

Out[240]: 'Sueña el r'

In [241]: f2 = open(path, mode="rb") # Binary mode

In [242]: f2.read(10)

Out[242]: b'Sue\xc3\xb1a el 'The read method advances the file object position by the number of bytes read. tell gives you the current position:

In [243]: f1.tell()

Out[243]: 11

In [244]: f2.tell()

Out[244]: 10Even though we read 10 characters from the file f1 opened in text mode, the position is 11 because it took that many bytes to decode 10 characters using the default encoding. You can check the default encoding in the sys module:

In [245]: import sys

In [246]: sys.getdefaultencoding()

Out[246]: 'utf-8'To get consistent behavior across platforms, it is best to pass an encoding (such as encoding="utf-8", which is widely used) when opening files.

seek changes the file position to the indicated byte in the file:

In [247]: f1.seek(3)

Out[247]: 3

In [248]: f1.read(1)

Out[248]: 'ñ'

In [249]: f1.tell()

Out[249]: 5Lastly, we remember to close the files:

In [250]: f1.close()

In [251]: f2.close()To write text to a file, you can use the file’s write or writelines methods. For example, we could create a version of examples/segismundo.txt with no blank lines like so:

In [252]: path

Out[252]: 'examples/segismundo.txt'

In [253]: with open("tmp.txt", mode="w") as handle:

.....: handle.writelines(x for x in open(path) if len(x) > 1)

In [254]: with open("tmp.txt") as f:

.....: lines = f.readlines()

In [255]: lines

Out[255]:

['Sueña el rico en su riqueza,\n',

'que más cuidados le ofrece;\n',

'sueña el pobre que padece\n',

'su miseria y su pobreza;\n',

'sueña el que a medrar empieza,\n',

'sueña el que afana y pretende,\n',

'sueña el que agravia y ofende,\n',

'y en el mundo, en conclusión,\n',

'todos sueñan lo que son,\n',

'aunque ninguno lo entiende.\n']See Table 3.4 for many of the most commonly used file methods.

| Method/attribute | Description |

|---|---|

read([size]) |

Return data from file as bytes or string depending on the file mode, with optional size argument indicating the number of bytes or string characters to read |

readable() |

Return True if the file supports read operations |

readlines([size]) |

Return list of lines in the file, with optional size argument |

write(string) |

Write passed string to file |

writable() |

Return True if the file supports write operations |

writelines(strings) |

Write passed sequence of strings to the file |

close() |

Close the file object |

flush() |

Flush the internal I/O buffer to disk |

seek(pos) |

Move to indicated file position (integer) |

seekable() |

Return True if the file object supports seeking and thus random access (some file-like objects do not) |

tell() |

Return current file position as integer |

closed |

True if the file is closed |

encoding |

The encoding used to interpret bytes in the file as Unicode (typically UTF-8) |

Bytes and Unicode with Files

The default behavior for Python files (whether readable or writable) is text mode, which means that you intend to work with Python strings (i.e., Unicode). This contrasts with binary mode, which you can obtain by appending b to the file mode. Revisiting the file (which contains non-ASCII characters with UTF-8 encoding) from the previous section, we have:

In [258]: with open(path) as f:

.....: chars = f.read(10)

In [259]: chars

Out[259]: 'Sueña el r'

In [260]: len(chars)

Out[260]: 10UTF-8 is a variable-length Unicode encoding, so when I request some number of characters from the file, Python reads enough bytes (which could be as few as 10 or as many as 40 bytes) from the file to decode that many characters. If I open the file in "rb" mode instead, read requests that exact number of bytes:

In [261]: with open(path, mode="rb") as f:

.....: data = f.read(10)

In [262]: data

Out[262]: b'Sue\xc3\xb1a el 'Depending on the text encoding, you may be able to decode the bytes to a str object yourself, but only if each of the encoded Unicode characters is fully formed:

In [263]: data.decode("utf-8")

Out[263]: 'Sueña el '

In [264]: data[:4].decode("utf-8")

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

UnicodeDecodeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-264-846a5c2fed34> in <module>

----> 1 data[:4].decode("utf-8")

UnicodeDecodeError: 'utf-8' codec can't decode byte 0xc3 in position 3: unexpecte

d end of dataText mode, combined with the encoding option of open, provides a convenient way to convert from one Unicode encoding to another:

In [265]: sink_path = "sink.txt"

In [266]: with open(path) as source:

.....: with open(sink_path, "x", encoding="iso-8859-1") as sink:

.....: sink.write(source.read())

In [267]: with open(sink_path, encoding="iso-8859-1") as f:

.....: print(f.read(10))

Sueña el rBeware using seek when opening files in any mode other than binary. If the file position falls in the middle of the bytes defining a Unicode character, then subsequent reads will result in an error:

In [269]: f = open(path, encoding='utf-8')

In [270]: f.read(5)

Out[270]: 'Sueña'

In [271]: f.seek(4)

Out[271]: 4

In [272]: f.read(1)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

UnicodeDecodeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-272-5a354f952aa4> in <module>

----> 1 f.read(1)

~/miniforge-x86/envs/book-env/lib/python3.10/codecs.py in decode(self, input, fin

al)

320 # decode input (taking the buffer into account)

321 data = self.buffer + input

--> 322 (result, consumed) = self._buffer_decode(data, self.errors, final

)

323 # keep undecoded input until the next call

324 self.buffer = data[consumed:]

UnicodeDecodeError: 'utf-8' codec can't decode byte 0xb1 in position 0: invalid s

tart byte

In [273]: f.close()If you find yourself regularly doing data analysis on non-ASCII text data, mastering Python's Unicode functionality will prove valuable. See Python's online documentation for much more.

3.4 Conclusion

With some of the basics of the Python environment and language now under your belt, it is time to move on and learn about NumPy and array-oriented computing in Python.