9 Plotting and Visualization

Making informative visualizations (sometimes called plots) is one of the most important tasks in data analysis. It may be a part of the exploratory process—for example, to help identify outliers or needed data transformations, or as a way of generating ideas for models. For others, building an interactive visualization for the web may be the end goal. Python has many add-on libraries for making static or dynamic visualizations, but I’ll be mainly focused on matplotlib and libraries that build on top of it.

matplotlib is a desktop plotting package designed for creating plots and figures suitable for publication. The project was started by John Hunter in 2002 to enable a MATLAB-like plotting interface in Python. The matplotlib and IPython communities have collaborated to simplify interactive plotting from the IPython shell (and now, Jupyter notebook). matplotlib supports various GUI backends on all operating systems and can export visualizations to all of the common vector and raster graphics formats (PDF, SVG, JPG, PNG, BMP, GIF, etc.). With the exception of a few diagrams, nearly all of the graphics in this book were produced using matplotlib.

Over time, matplotlib has spawned a number of add-on toolkits for data visualization that use matplotlib for their underlying plotting. One of these is seaborn, which we explore later in this chapter.

The simplest way to follow the code examples in the chapter is to output plots in the Jupyter notebook. To set this up, execute the following statement in a Jupyter notebook:

%matplotlib inlineSince this book's first edition in 2012, many new data visualization libraries have been created, some of which (like Bokeh and Altair) take advantage of modern web technology to create interactive visualizations that integrate well with the Jupyter notebook. Rather than use multiple visualization tools in this book, I decided to stick with matplotlib for teaching the fundamentals, in particular since pandas has good integration with matplotlib. You can adapt the principles from this chapter to learn how to use other visualization libraries as well.

9.1 A Brief matplotlib API Primer

With matplotlib, we use the following import convention:

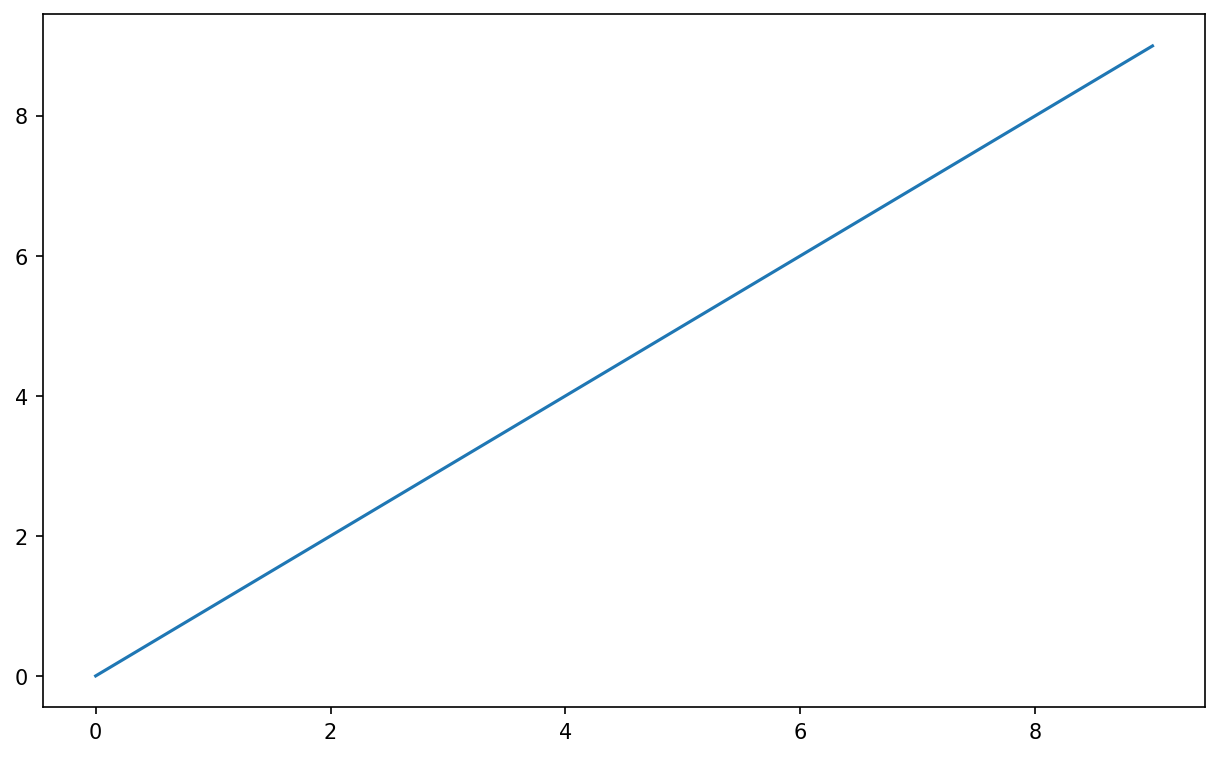

In [13]: import matplotlib.pyplot as pltAfter running %matplotlib notebook in Jupyter (or simply %matplotlib in IPython), we can try creating a simple plot. If everything is set up right, a line plot like Simple line plot should appear:

In [14]: data = np.arange(10)

In [15]: data

Out[15]: array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9])

In [16]: plt.plot(data)While libraries like seaborn and pandas's built-in plotting functions will deal with many of the mundane details of making plots, should you wish to customize them beyond the function options provided, you will need to learn a bit about the matplotlib API.

There is not enough room in the book to give comprehensive treatment of the breadth and depth of functionality in matplotlib. It should be enough to teach you the ropes to get up and running. The matplotlib gallery and documentation are the best resource for learning advanced features.

Figures and Subplots

Plots in matplotlib reside within a Figure object. You can create a new figure with plt.figure:

In [17]: fig = plt.figure()In IPython, if you first run %matplotlib to set up the matplotlib integration, an empty plot window will appear, but in Jupyter nothing will be shown until we use a few more commands.

plt.figure has a number of options; notably, figsize will guarantee the figure has a certain size and aspect ratio if saved to disk.

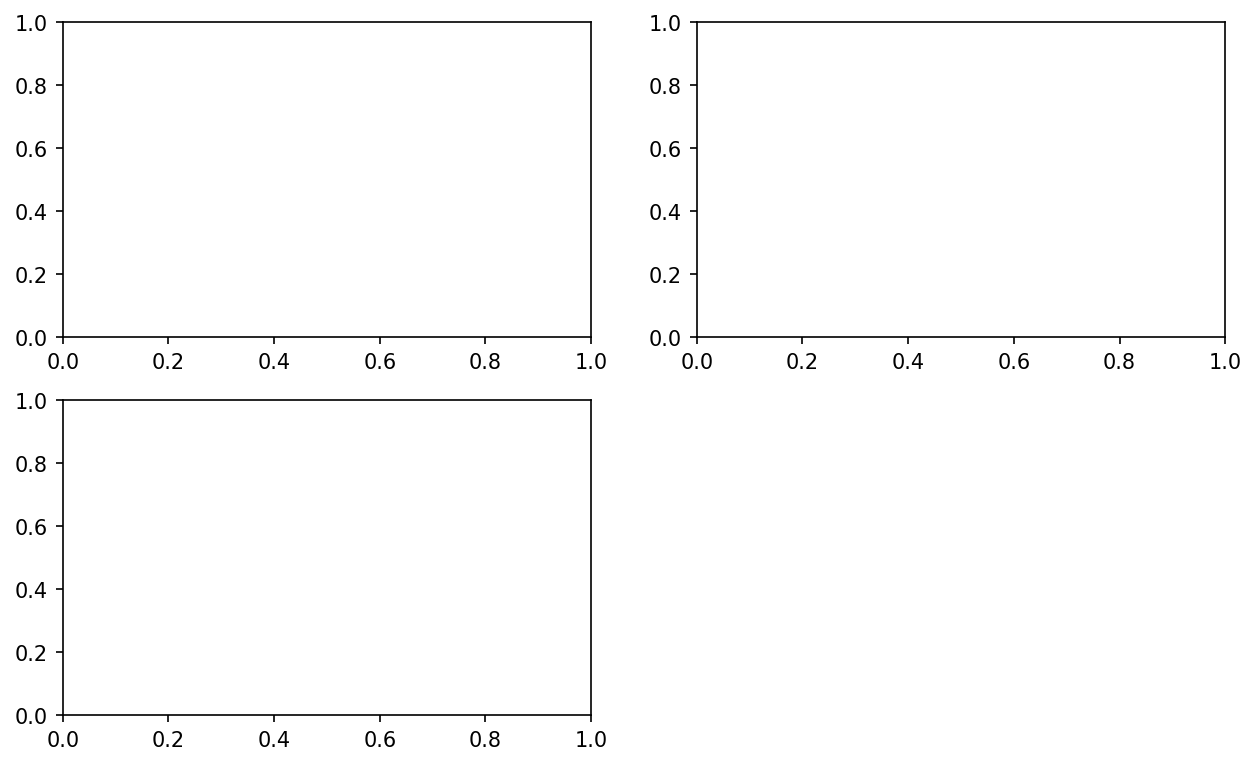

You can’t make a plot with a blank figure. You have to create one or more subplots using add_subplot:

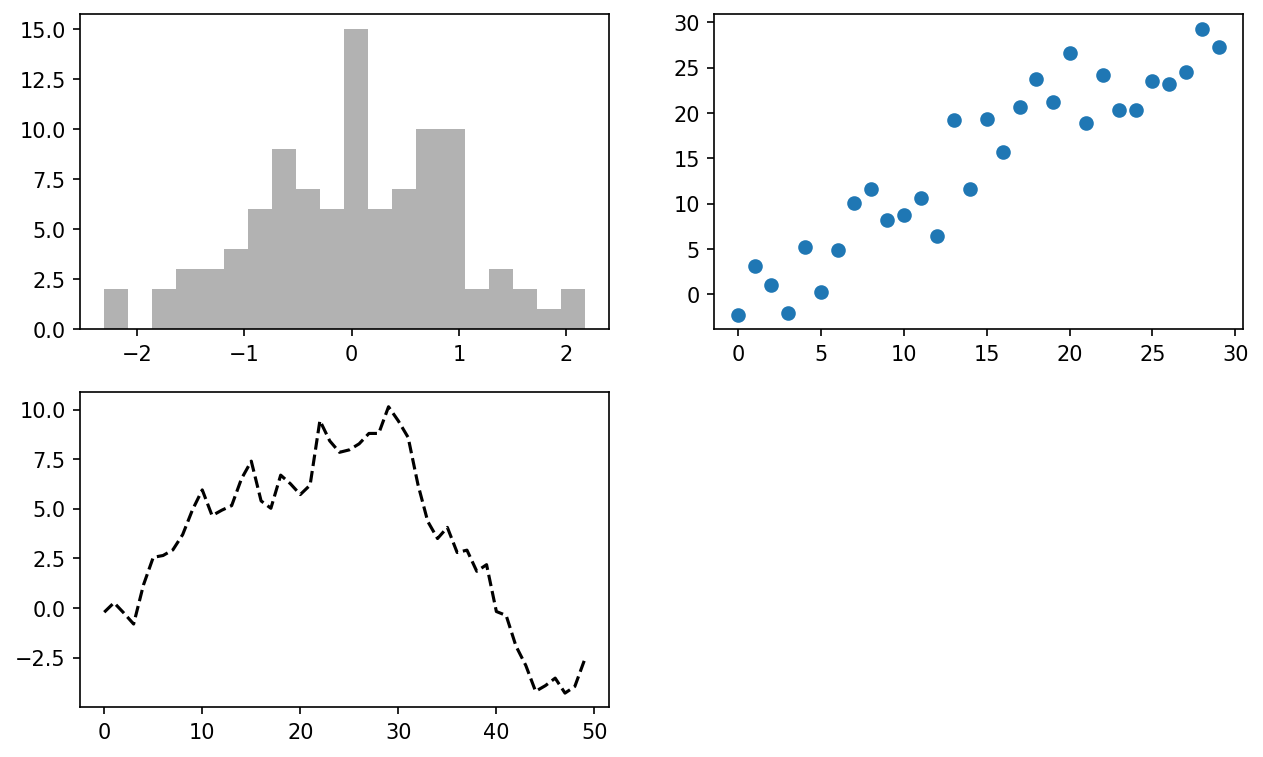

In [18]: ax1 = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, 1)This means that the figure should be 2 × 2 (so up to four plots in total), and we’re selecting the first of four subplots (numbered from 1). If you create the next two subplots, you’ll end up with a visualization that looks like An empty matplotlib figure with three subplots:

In [19]: ax2 = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, 2)

In [20]: ax3 = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, 3)One nuance of using Jupyter notebooks is that plots are reset after each cell is evaluated, so you must put all of the plotting commands in a single notebook cell.

Here we run all of these commands in the same cell:

fig = plt.figure()

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, 1)

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, 2)

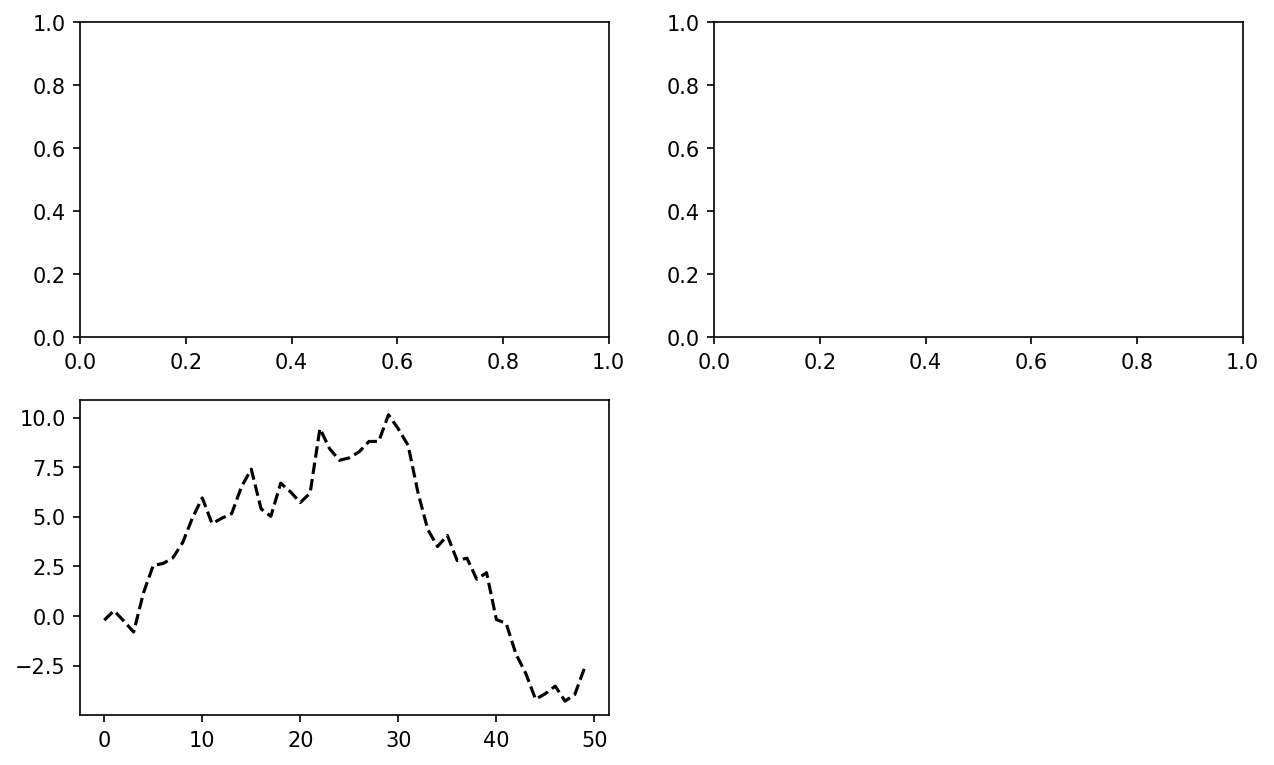

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, 3)These plot axis objects have various methods that create different types of plots, and it is preferred to use the axis methods over the top-level plotting functions like plt.plot. For example, we could make a line plot with the plot method (see Data visualization after a single plot):

In [21]: ax3.plot(np.random.standard_normal(50).cumsum(), color="black",

....: linestyle="dashed")You may notice output like <matplotlib.lines.Line2D at ...> when you run this. matplotlib returns objects that reference the plot subcomponent that was just added. A lot of the time you can safely ignore this output, or you can put a semicolon at the end of the line to suppress the output.

The additional options instruct matplotlib to plot a black dashed line. The objects returned by fig.add_subplot here are AxesSubplot objects, on which you can directly plot on the other empty subplots by calling each one’s instance method (see Data visualization after additional plots):

In [22]: ax1.hist(np.random.standard_normal(100), bins=20, color="black", alpha=0

.3);

In [23]: ax2.scatter(np.arange(30), np.arange(30) + 3 * np.random.standard_normal

(30));The style option alpha=0.3 sets the transparency of the overlaid plot.

You can find a comprehensive catalog of plot types in the matplotlib documentation.

To make creating a grid of subplots more convenient, matplotlib includes a plt.subplots method that creates a new figure and returns a NumPy array containing the created subplot objects:

In [25]: fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 3)

In [26]: axes

Out[26]:

array([[<Axes: >, <Axes: >, <Axes: >],

[<Axes: >, <Axes: >, <Axes: >]], dtype=object)The axes array can then be indexed like a two-dimensional array; for example, axes[0, 1] refers to the subplot in the top row at the center. You can also indicate that subplots should have the same x- or y-axis using sharex and sharey, respectively. This can be useful when you're comparing data on the same scale; otherwise, matplotlib autoscales plot limits independently. See Table 9.1 for more on this method.

| Argument | Description |

|---|---|

nrows |

Number of rows of subplots |

ncols |

Number of columns of subplots |

sharex |

All subplots should use the same x-axis ticks (adjusting the xlim will affect all subplots) |

sharey |

All subplots should use the same y-axis ticks (adjusting the ylim will affect all subplots) |

subplot_kw |

Dictionary of keywords passed to add_subplot call used to create each subplot |

**fig_kw |

Additional keywords to subplots are used when creating the figure, such as plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(8, 6)) |

Adjusting the spacing around subplots

By default, matplotlib leaves a certain amount of padding around the outside of the subplots and in spacing between subplots. This spacing is all specified relative to the height and width of the plot, so that if you resize the plot either programmatically or manually using the GUI window, the plot will dynamically adjust itself. You can change the spacing using the subplots_adjust method on Figure objects:

subplots_adjust(left=None, bottom=None, right=None, top=None,

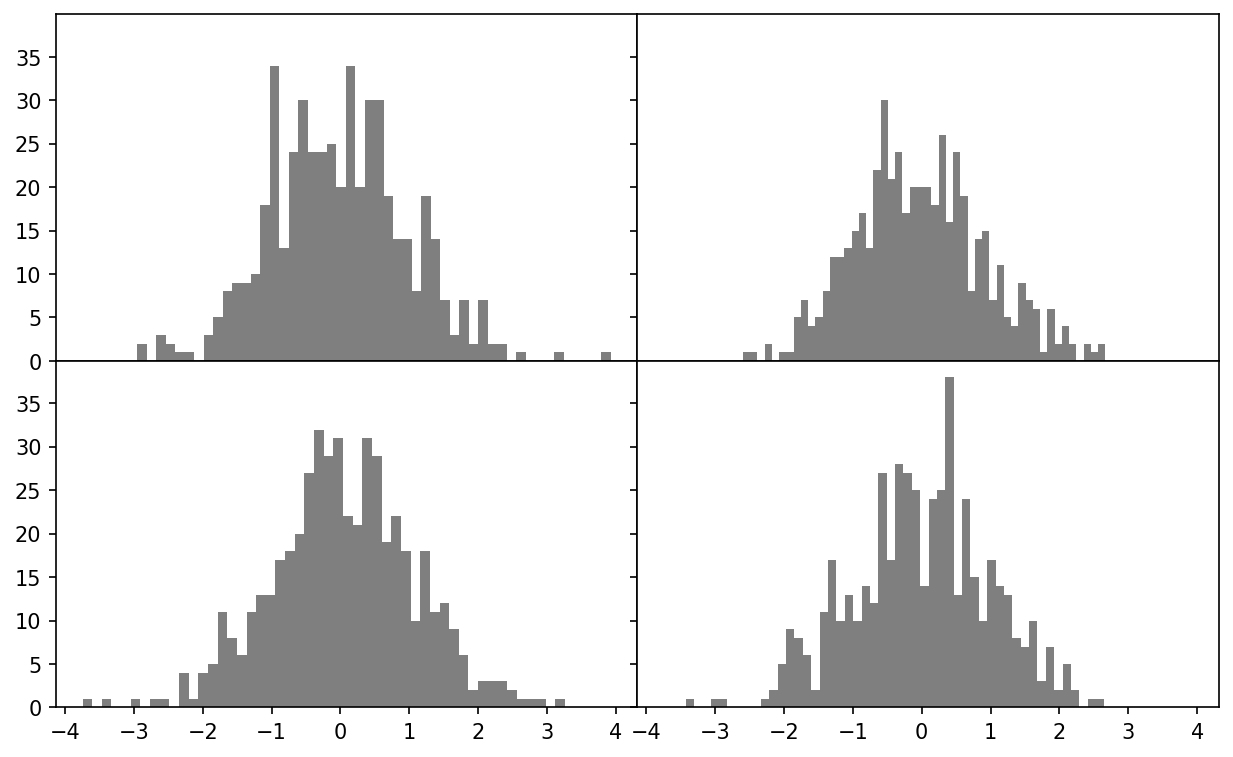

wspace=None, hspace=None)wspace and hspace control the percent of the figure width and figure height, respectively, to use as spacing between subplots. Here is a small example you can execute in Jupyter where I shrink the spacing all the way to zero (see Data visualization with no inter-subplot spacing):

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, sharex=True, sharey=True)

for i in range(2):

for j in range(2):

axes[i, j].hist(np.random.standard_normal(500), bins=50,

color="black", alpha=0.5)

fig.subplots_adjust(wspace=0, hspace=0)You may notice that the axis labels overlap. matplotlib doesn’t check whether the labels overlap, so in a case like this you would need to fix the labels yourself by specifying explicit tick locations and tick labels (we'll look at how to do this in the later section Ticks, Labels, and Legends).

Colors, Markers, and Line Styles

matplotlib’s line plot function accepts arrays of x and y coordinates and optional color styling options. For example, to plot x versus y with green dashes, you would execute:

ax.plot(x, y, linestyle="--", color="green")A number of color names are provided for commonly used colors, but you can use any color on the spectrum by specifying its hex code (e.g., "#CECECE"). You can see some of the supported line styles by looking at the docstring for plt.plot (use plt.plot? in IPython or Jupyter). A more comprehensive reference is available in the online documentation.

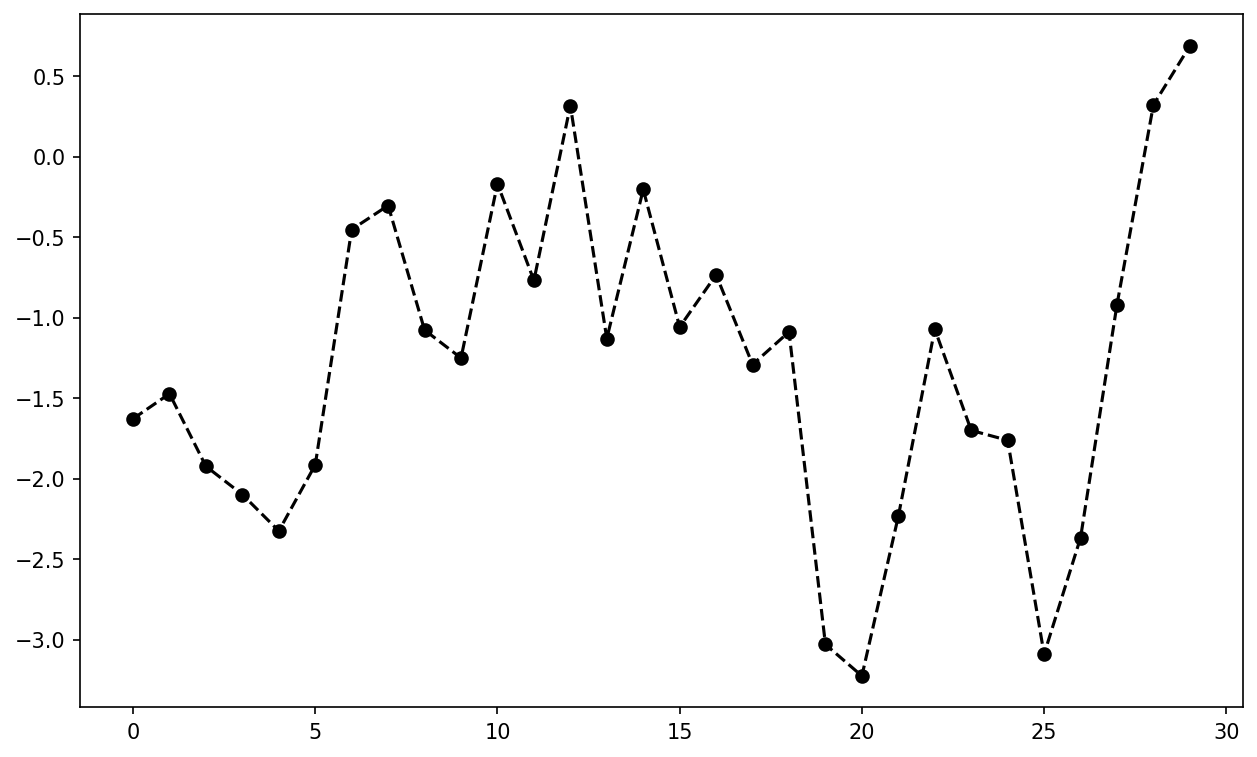

Line plots can additionally have markers to highlight the actual data points. Since matplotlib's plot function creates a continuous line plot, interpolating between points, it can occasionally be unclear where the points lie. The marker can be supplied as an additional styling option (see Line plot with markers):

In [31]: ax = fig.add_subplot()

In [32]: ax.plot(np.random.standard_normal(30).cumsum(), color="black",

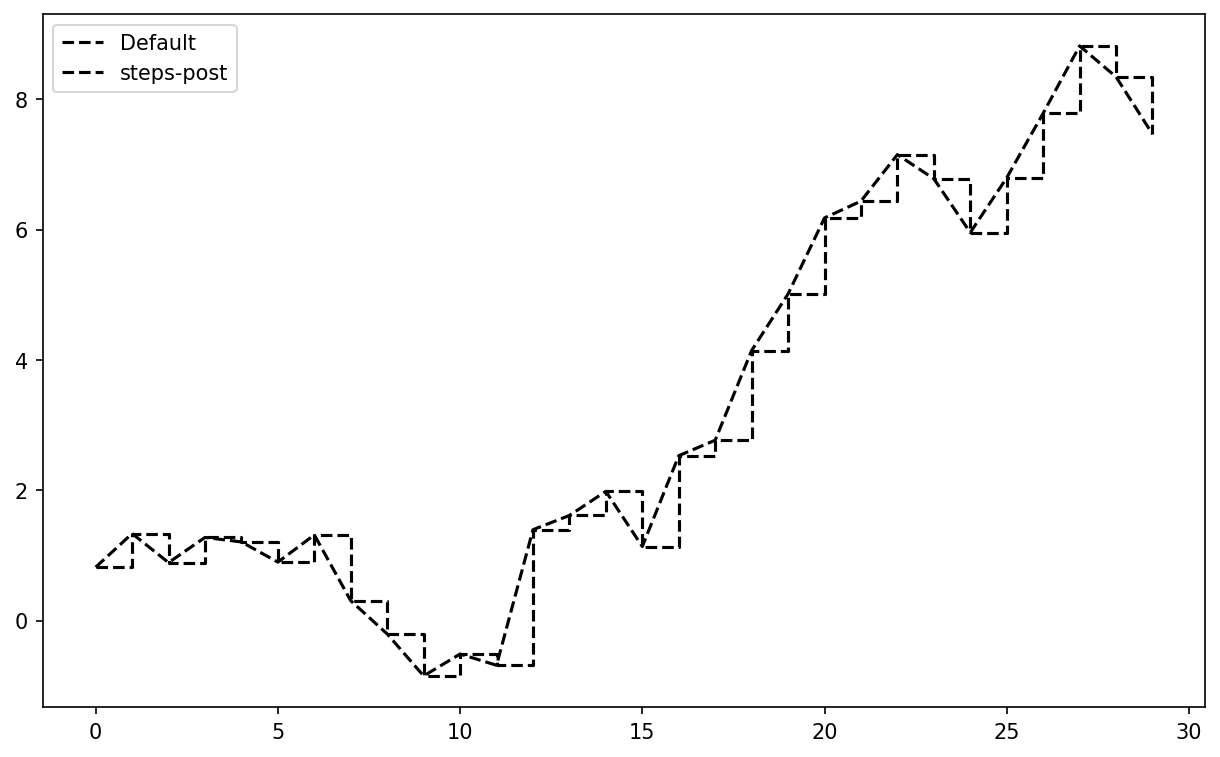

....: linestyle="dashed", marker="o");For line plots, you will notice that subsequent points are linearly interpolated by default. This can be altered with the drawstyle option (see Line plot with different drawstyle options):

In [34]: fig = plt.figure()

In [35]: ax = fig.add_subplot()

In [36]: data = np.random.standard_normal(30).cumsum()

In [37]: ax.plot(data, color="black", linestyle="dashed", label="Default");

In [38]: ax.plot(data, color="black", linestyle="dashed",

....: drawstyle="steps-post", label="steps-post");

In [39]: ax.legend()Here, since we passed the label arguments to plot, we are able to create a plot legend to identify each line using ax.legend. I discuss legends more in Ticks, Labels, and Legends.

You must call ax.legend to create the legend, whether or not you passed the label options when plotting the data.

Ticks, Labels, and Legends

Most kinds of plot decorations can be accessed through methods on matplotlib axes objects. This includes methods like xlim, xticks, and xticklabels. These control the plot range, tick locations, and tick labels, respectively. They can be used in two ways:

Called with no arguments returns the current parameter value (e.g.,

ax.xlim()returns the current x-axis plotting range)Called with parameters sets the parameter value (e.g.,

ax.xlim([0, 10])sets the x-axis range to 0 to 10)

All such methods act on the active or most recently created AxesSubplot. Each corresponds to two methods on the subplot object itself; in the case of xlim, these are ax.get_xlim and ax.set_xlim.

Setting the title, axis labels, ticks, and tick labels

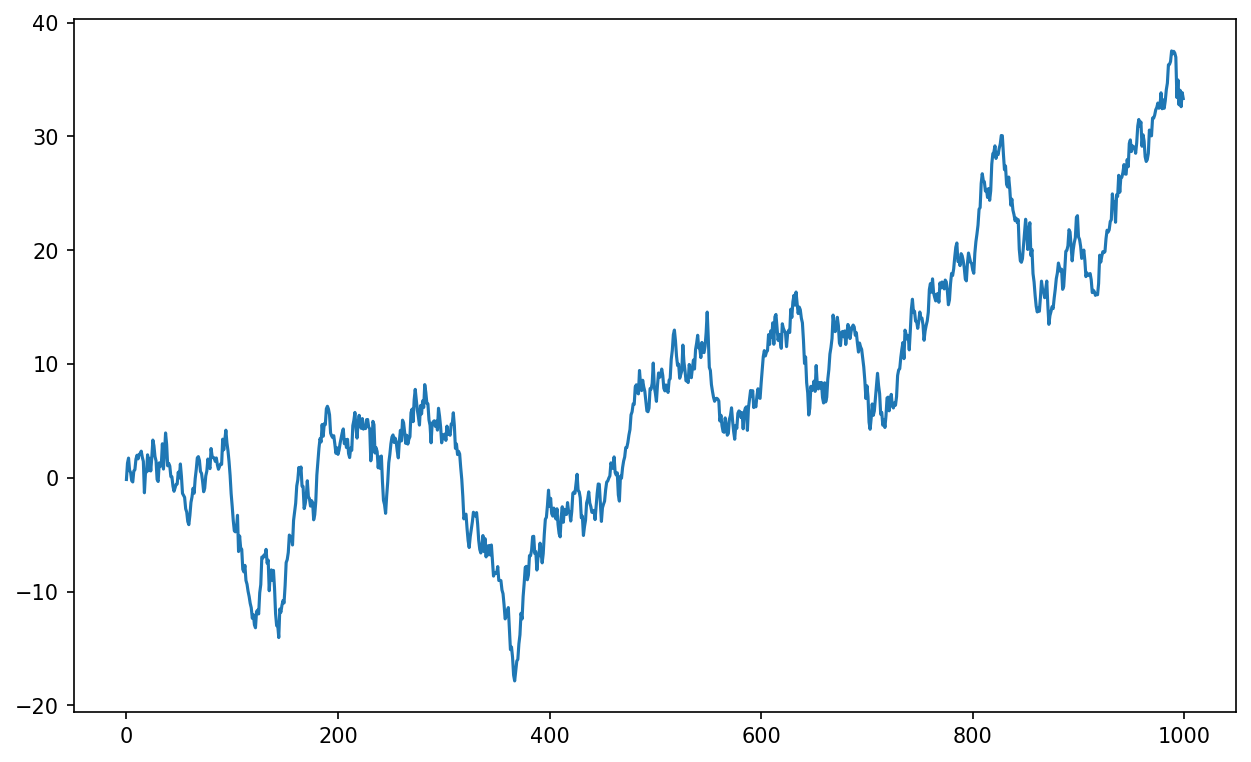

To illustrate customizing the axes, I’ll create a simple figure and plot of a random walk (see Simple plot for illustrating xticks (with default labels)):

In [40]: fig, ax = plt.subplots()

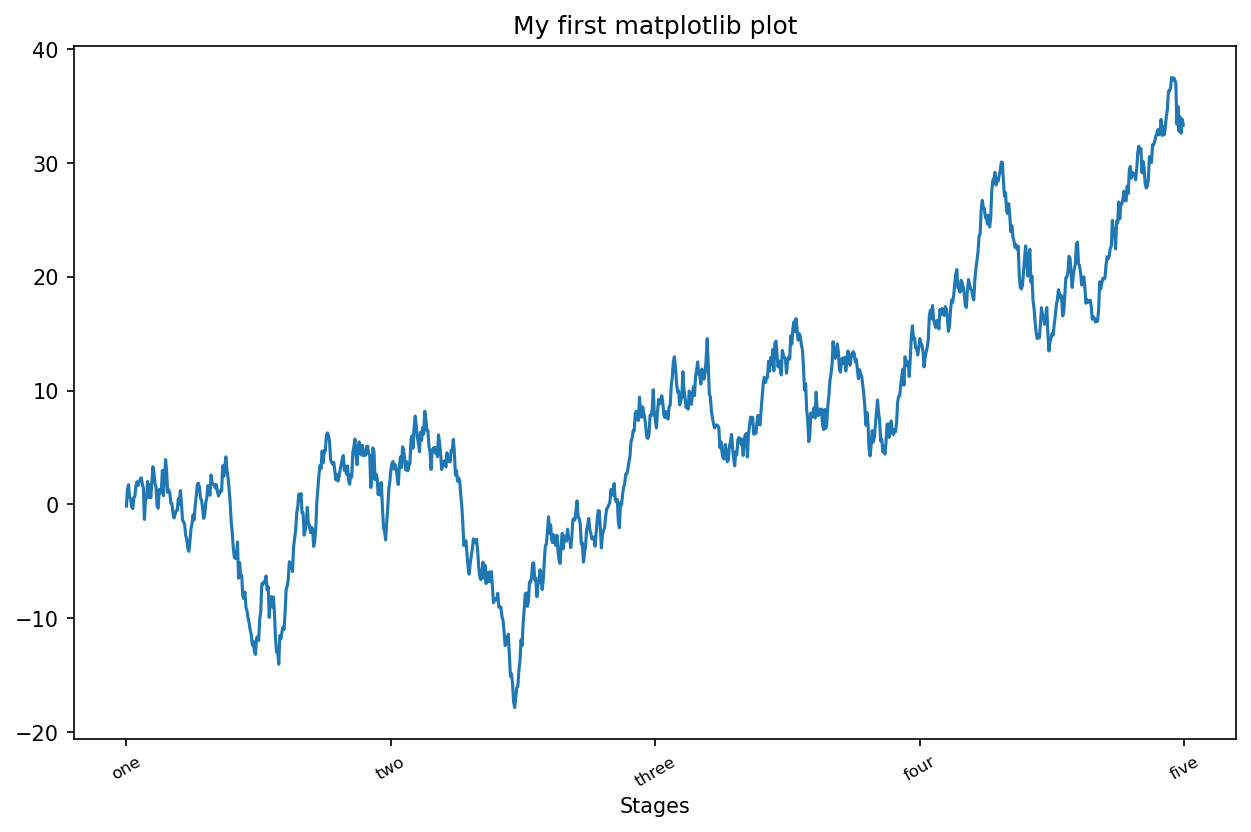

In [41]: ax.plot(np.random.standard_normal(1000).cumsum());To change the x-axis ticks, it’s easiest to use set_xticks and set_xticklabels. The former instructs matplotlib where to place the ticks along the data range; by default these locations will also be the labels. But we can set any other values as the labels using set_xticklabels:

In [42]: ticks = ax.set_xticks([0, 250, 500, 750, 1000])

In [43]: labels = ax.set_xticklabels(["one", "two", "three", "four", "five"],

....: rotation=30, fontsize=8)The rotation option sets the x tick labels at a 30-degree rotation. Lastly, set_xlabel gives a name to the x-axis, and set_title is the subplot title (see Simple plot for illustrating custom xticks for the resulting figure):

In [44]: ax.set_xlabel("Stages")

Out[44]: Text(0.5, 6.666666666666652, 'Stages')

In [45]: ax.set_title("My first matplotlib plot")Modifying the y-axis consists of the same process, substituting y for x in this example. The axes class has a set method that allows batch setting of plot properties. From the prior example, we could also have written:

ax.set(title="My first matplotlib plot", xlabel="Stages")Adding legends

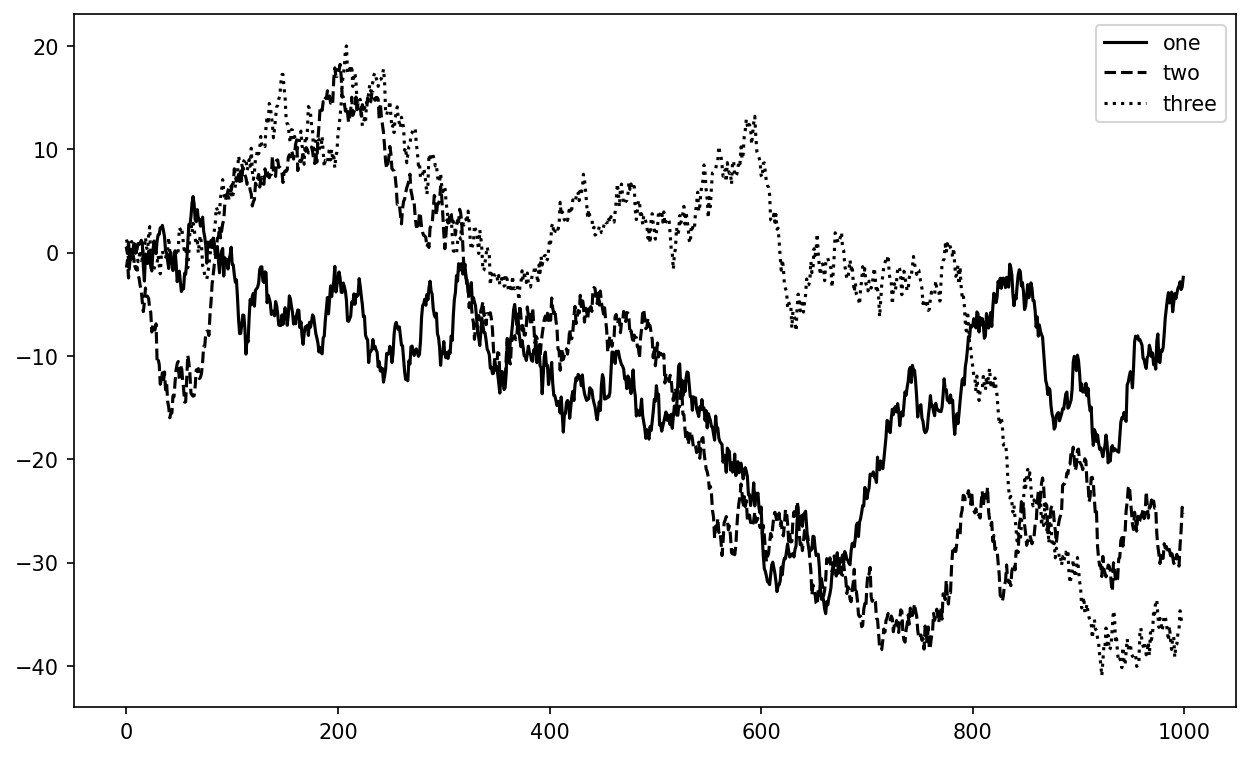

Legends are another critical element for identifying plot elements. There are a couple of ways to add one. The easiest is to pass the label argument when adding each piece of the plot:

In [46]: fig, ax = plt.subplots()

In [47]: ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", label="one");

In [48]: ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", linestyle="dashed

",

....: label="two");

In [49]: ax.plot(np.random.randn(1000).cumsum(), color="black", linestyle="dotted

",

....: label="three");Once you’ve done this, you can call ax.legend() to automatically create a legend. The resulting plot is in Simple plot with three lines and legend:

In [50]: ax.legend()The legend method has several other choices for the location loc argument. See the docstring (with ax.legend?) for more information.

The loc legend option tells matplotlib where to place the plot. The default is "best", which tries to choose a location that is most out of the way. To exclude one or more elements from the legend, pass no label or label="_nolegend_".

Annotations and Drawing on a Subplot

In addition to the standard plot types, you may wish to draw your own plot annotations, which could consist of text, arrows, or other shapes. You can add annotations and text using the text, arrow, and annotate functions. text draws text at given coordinates (x, y) on the plot with optional custom styling:

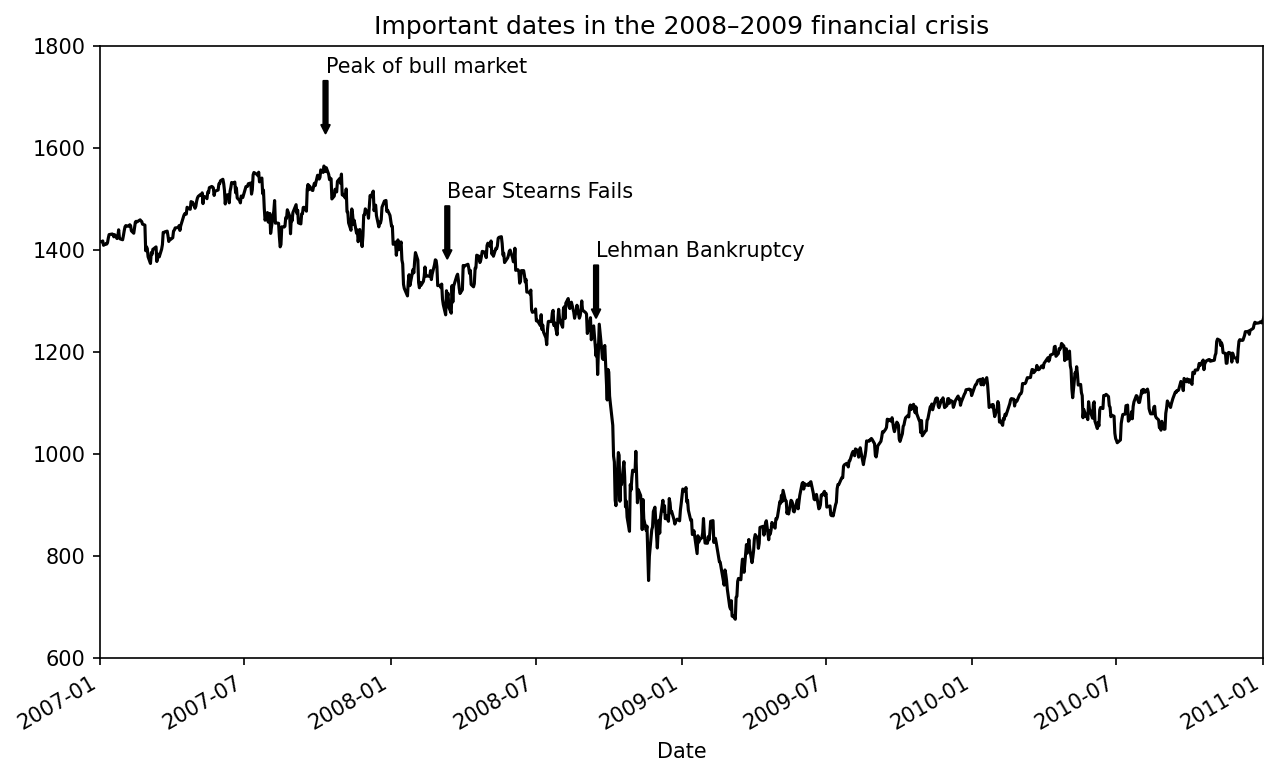

ax.text(x, y, "Hello world!",

family="monospace", fontsize=10)Annotations can draw both text and arrows arranged appropriately. As an example, let’s plot the closing S&P 500 index price since 2007 (obtained from Yahoo! Finance) and annotate it with some of the important dates from the 2008–2009 financial crisis. You can run this code example in a single cell in a Jupyter notebook. See Important dates in the 2008–2009 financial crisis for the result:

from datetime import datetime

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

data = pd.read_csv("examples/spx.csv", index_col=0, parse_dates=True)

spx = data["SPX"]

spx.plot(ax=ax, color="black")

crisis_data = [

(datetime(2007, 10, 11), "Peak of bull market"),

(datetime(2008, 3, 12), "Bear Stearns Fails"),

(datetime(2008, 9, 15), "Lehman Bankruptcy")

]

for date, label in crisis_data:

ax.annotate(label, xy=(date, spx.asof(date) + 75),

xytext=(date, spx.asof(date) + 225),

arrowprops=dict(facecolor="black", headwidth=4, width=2,

headlength=4),

horizontalalignment="left", verticalalignment="top")

# Zoom in on 2007-2010

ax.set_xlim(["1/1/2007", "1/1/2011"])

ax.set_ylim([600, 1800])

ax.set_title("Important dates in the 2008–2009 financial crisis")There are a couple of important points to highlight in this plot. The ax.annotate method can draw labels at the indicated x and y coordinates. We use the set_xlim and set_ylim methods to manually set the start and end boundaries for the plot rather than using matplotlib's default. Lastly, ax.set_title adds a main title to the plot.

See the online matplotlib gallery for many more annotation examples to learn from.

Drawing shapes requires some more care. matplotlib has objects that represent many common shapes, referred to as patches. Some of these, like Rectangle and Circle, are found in matplotlib.pyplot, but the full set is located in matplotlib.patches.

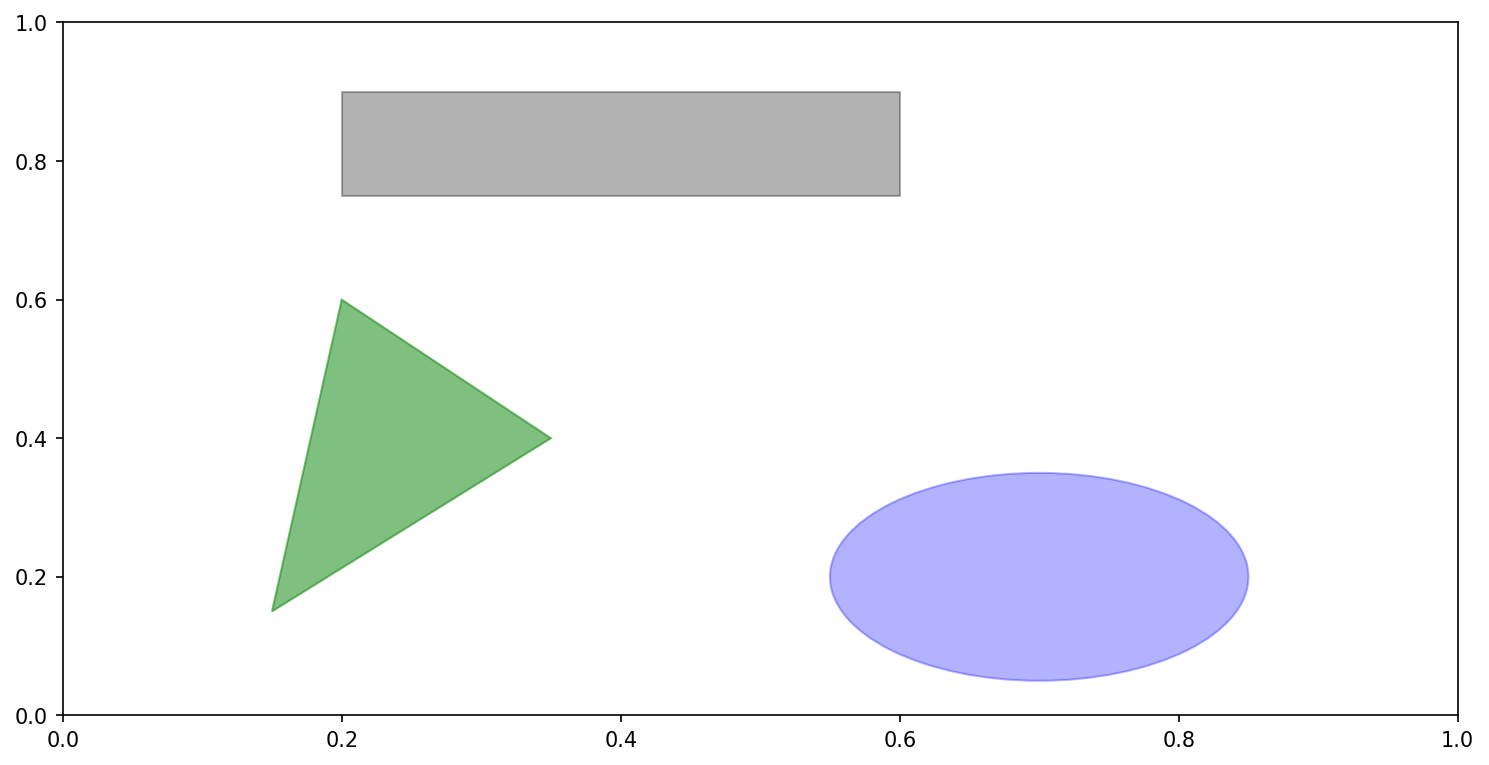

To add a shape to a plot, you create the patch object and add it to a subplot ax by passing the patch to ax.add_patch (see Data visualization composed from three different patches):

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

rect = plt.Rectangle((0.2, 0.75), 0.4, 0.15, color="black", alpha=0.3)

circ = plt.Circle((0.7, 0.2), 0.15, color="blue", alpha=0.3)

pgon = plt.Polygon([[0.15, 0.15], [0.35, 0.4], [0.2, 0.6]],

color="green", alpha=0.5)

ax.add_patch(rect)

ax.add_patch(circ)

ax.add_patch(pgon)If you look at the implementation of many familiar plot types, you will see that they are assembled from patches.

Saving Plots to File

You can save the active figure to file using the figure object’s savefig instance method. For example, to save an SVG version of a figure, you need only type:

fig.savefig("figpath.svg")The file type is inferred from the file extension. So if you used .pdf instead, you would get a PDF. One important option that I use frequently for publishing graphics is dpi, which controls the dots-per-inch resolution. To get the same plot as a PNG at 400 DPI, you would do:

fig.savefig("figpath.png", dpi=400)See Table 9.2 for a list of some other options for savefig. For a comprehensive listing, refer to the docstring in IPython or Jupyter.

| Argument | Description |

|---|---|

fname |

String containing a filepath or a Python file-like object. The figure format is inferred from the file extension (e.g., .pdf for PDF or .png for PNG). |

dpi |

The figure resolution in dots per inch; defaults to 100 in IPython or 72 in Jupyter out of the box but can be configured. |

facecolor, edgecolor |

The color of the figure background outside of the subplots; "w" (white), by default. |

format |

The explicit file format to use ("png", "pdf", "svg", "ps", "eps", ...). |

matplotlib Configuration

matplotlib comes configured with color schemes and defaults that are geared primarily toward preparing figures for publication. Fortunately, nearly all of the default behavior can be customized via global parameters governing figure size, subplot spacing, colors, font sizes, grid styles, and so on. One way to modify the configuration programmatically from Python is to use the rc method; for example, to set the global default figure size to be 10 × 10, you could enter:

plt.rc("figure", figsize=(10, 10))All of the current configuration settings are found in the plt.rcParams dictionary, and they can be restored to their default values by calling the plt.rcdefaults() function.

The first argument to rc is the component you wish to customize, such as "figure", "axes", "xtick", "ytick", "grid", "legend", or many others. After that can follow a sequence of keyword arguments indicating the new parameters. A convenient way to write down the options in your program is as a dictionary:

plt.rc("font", family="monospace", weight="bold", size=8)For more extensive customization and to see a list of all the options, matplotlib comes with a configuration file matplotlibrc in the matplotlib/mpl-data directory. If you customize this file and place it in your home directory titled .matplotlibrc, it will be loaded each time you use matplotlib.

As we'll see in the next section, the seaborn package has several built-in plot themes or styles that use matplotlib's configuration system internally.

9.2 Plotting with pandas and seaborn

matplotlib can be a fairly low-level tool. You assemble a plot from its base components: the data display (i.e., the type of plot: line, bar, box, scatter, contour, etc.), legend, title, tick labels, and other annotations.

In pandas, we may have multiple columns of data, along with row and column labels. pandas itself has built-in methods that simplify creating visualizations from DataFrame and Series objects. Another library is seaborn, a high-level statistical graphics library built on matplotlib. seaborn simplifies creating many common visualization types.

Line Plots

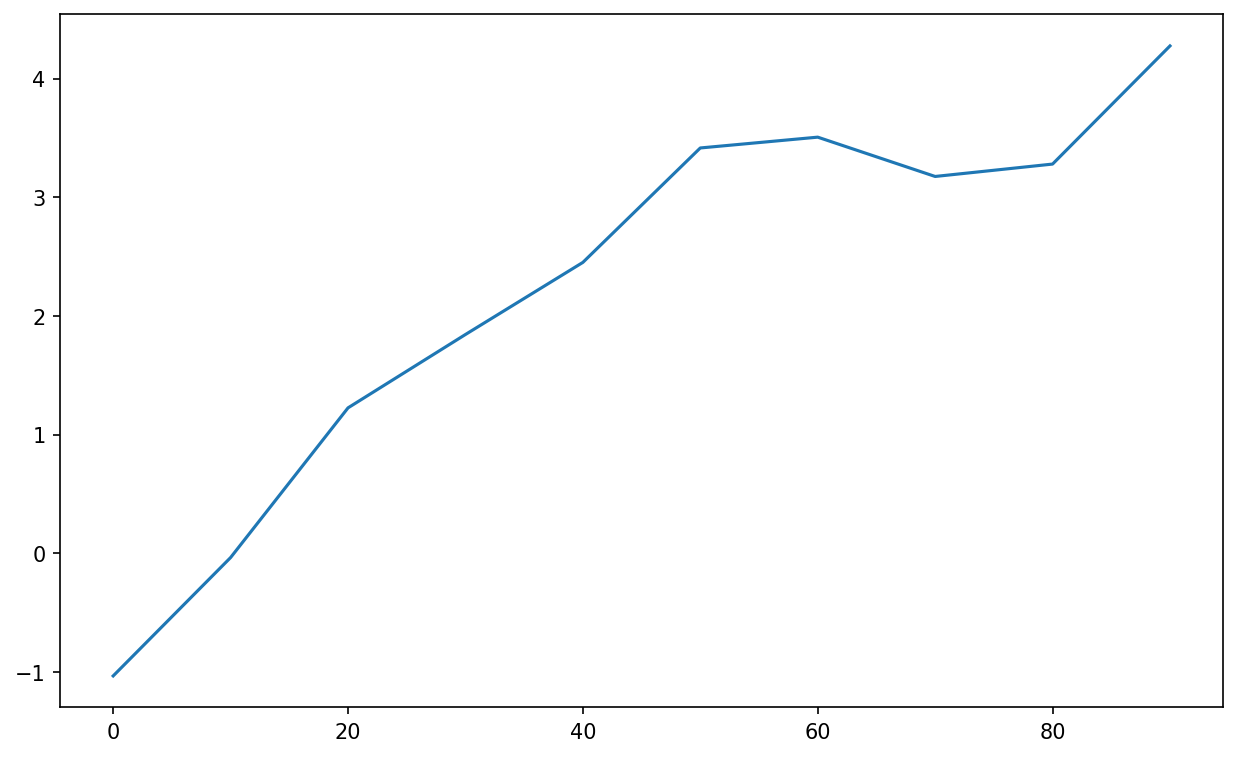

Series and DataFrame have a plot attribute for making some basic plot types. By default, plot() makes line plots (see Simple Series plot):

In [61]: s = pd.Series(np.random.standard_normal(10).cumsum(), index=np.arange(0,

100, 10))

In [62]: s.plot()The Series object’s index is passed to matplotlib for plotting on the x-axis, though you can disable this by passing use_index=False. The x-axis ticks and limits can be adjusted with the xticks and xlim options, and the y-axis respectively with yticks and ylim. See Table 9.3 for a partial listing of plot options. I’ll comment on a few more of them throughout this section and leave the rest for you to explore.

| Argument | Description |

|---|---|

label |

Label for plot legend |

ax |

matplotlib subplot object to plot on; if nothing passed, uses active matplotlib subplot |

style |

Style string, like "ko--", to be passed to matplotlib |

alpha |

The plot fill opacity (from 0 to 1) |

kind |

Can be "area", "bar", "barh", "density", "hist", "kde", "line", or "pie"; defaults to "line" |

figsize |

Size of the figure object to create |

logx |

Pass True for logarithmic scaling on the x axis; pass "sym" for symmetric logarithm that permits negative values |

logy |

Pass True for logarithmic scaling on the y axis; pass "sym" for symmetric logarithm that permits negative values |

title |

Title to use for the plot |

use_index |

Use the object index for tick labels |

rot |

Rotation of tick labels (0 through 360) |

xticks |

Values to use for x-axis ticks |

yticks |

Values to use for y-axis ticks |

xlim |

x-axis limits (e.g., [0, 10]) |

ylim |

y-axis limits |

grid |

Display axis grid (off by default) |

Most of pandas’s plotting methods accept an optional ax parameter, which can be a matplotlib subplot object. This gives you more flexible placement of subplots in a grid layout.

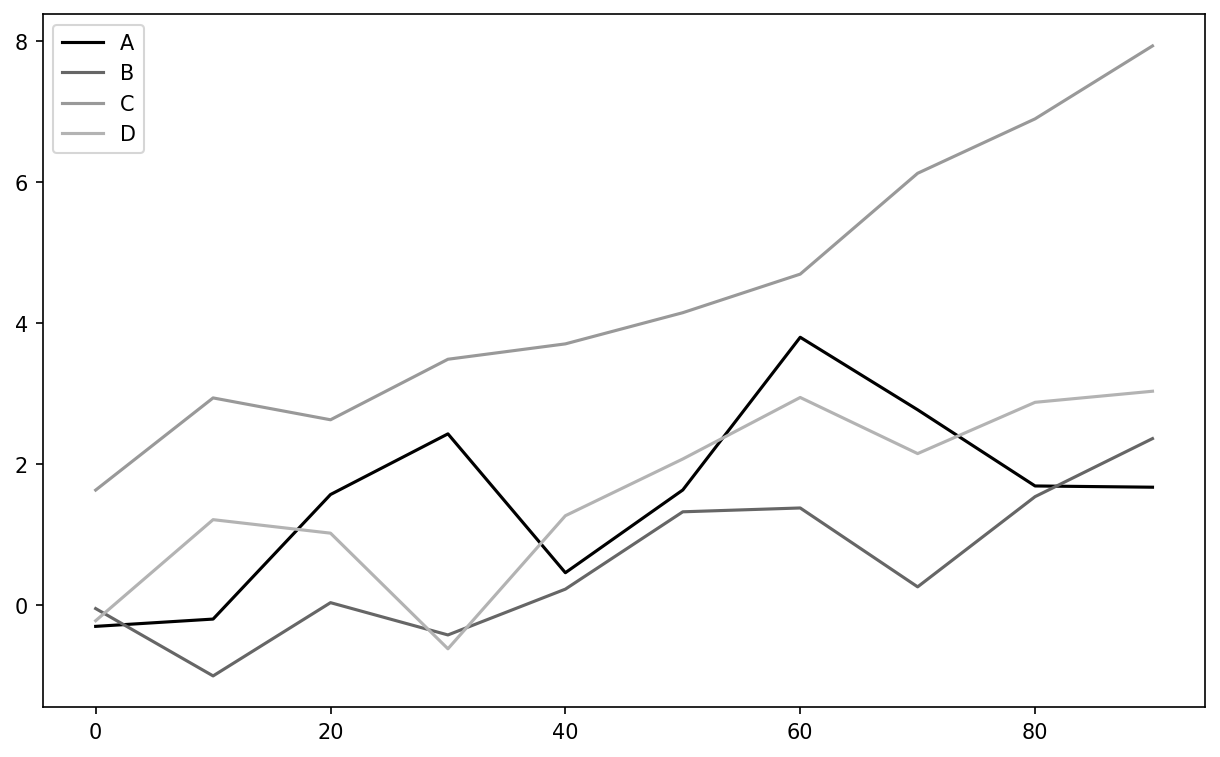

DataFrame’s plot method plots each of its columns as a different line on the same subplot, creating a legend automatically (see Simple DataFrame plot):

In [63]: df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.standard_normal((10, 4)).cumsum(0),

....: columns=["A", "B", "C", "D"],

....: index=np.arange(0, 100, 10))

In [64]: plt.style.use('grayscale')

In [65]: df.plot()Here I used plt.style.use('grayscale') to switch to a color scheme more suitable for black and white publication, since some readers will not be able to see the full color plots.

The plot attribute contains a "family" of methods for different plot types. For example, df.plot() is equivalent to df.plot.line(). We'll explore some of these methods next.

Additional keyword arguments to plot are passed through to the respective matplotlib plotting function, so you can further customize these plots by learning more about the matplotlib API.

DataFrame has a number of options allowing some flexibility for how the columns are handled, for example, whether to plot them all on the same subplot or to create separate subplots. See Table 9.4 for more on these.

| Argument | Description |

|---|---|

subplots |

Plot each DataFrame column in a separate subplot |

layouts |

2-tuple (rows, columns) providing layout of subplots |

sharex |

If subplots=True, share the same x-axis, linking ticks and limits |

sharey |

If subplots=True, share the same y-axis |

legend |

Add a subplot legend (True by default) |

sort_columns |

Plot columns in alphabetical order; by default uses existing column order |

For time series plotting, see Ch 11: Time Series.

Bar Plots

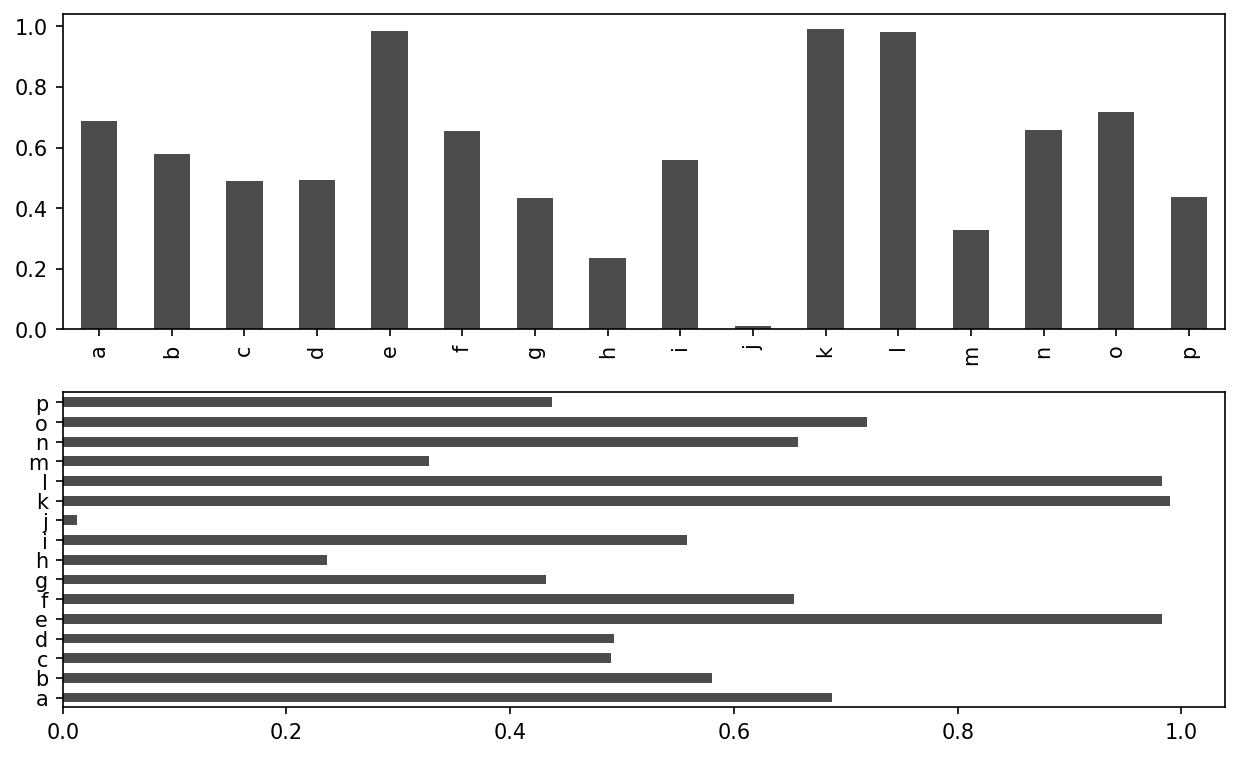

The plot.bar() and plot.barh() make vertical and horizontal bar plots, respectively. In this case, the Series or DataFrame index will be used as the x (bar) or y (barh) ticks (see Horizonal and vertical bar plot):

In [66]: fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 1)

In [67]: data = pd.Series(np.random.uniform(size=16), index=list("abcdefghijklmno

p"))

In [68]: data.plot.bar(ax=axes[0], color="black", alpha=0.7)

Out[68]: <Axes: >

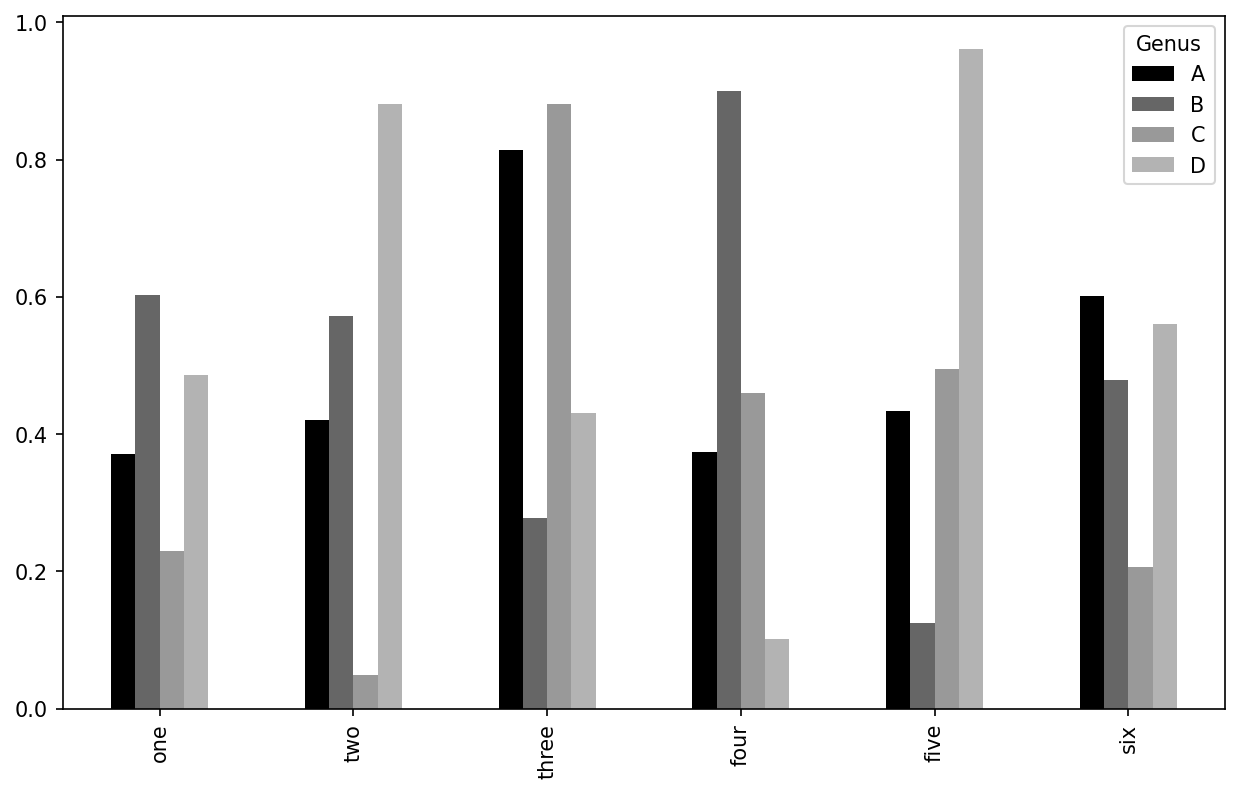

In [69]: data.plot.barh(ax=axes[1], color="black", alpha=0.7)With a DataFrame, bar plots group the values in each row in bars, side by side, for each value. See DataFrame bar plot:

In [71]: df = pd.DataFrame(np.random.uniform(size=(6, 4)),

....: index=["one", "two", "three", "four", "five", "six"],

....: columns=pd.Index(["A", "B", "C", "D"], name="Genus"))

In [72]: df

Out[72]:

Genus A B C D

one 0.370670 0.602792 0.229159 0.486744

two 0.420082 0.571653 0.049024 0.880592

three 0.814568 0.277160 0.880316 0.431326

four 0.374020 0.899420 0.460304 0.100843

five 0.433270 0.125107 0.494675 0.961825

six 0.601648 0.478576 0.205690 0.560547

In [73]: df.plot.bar()Note that the name “Genus” on the DataFrame’s columns is used to title the legend.

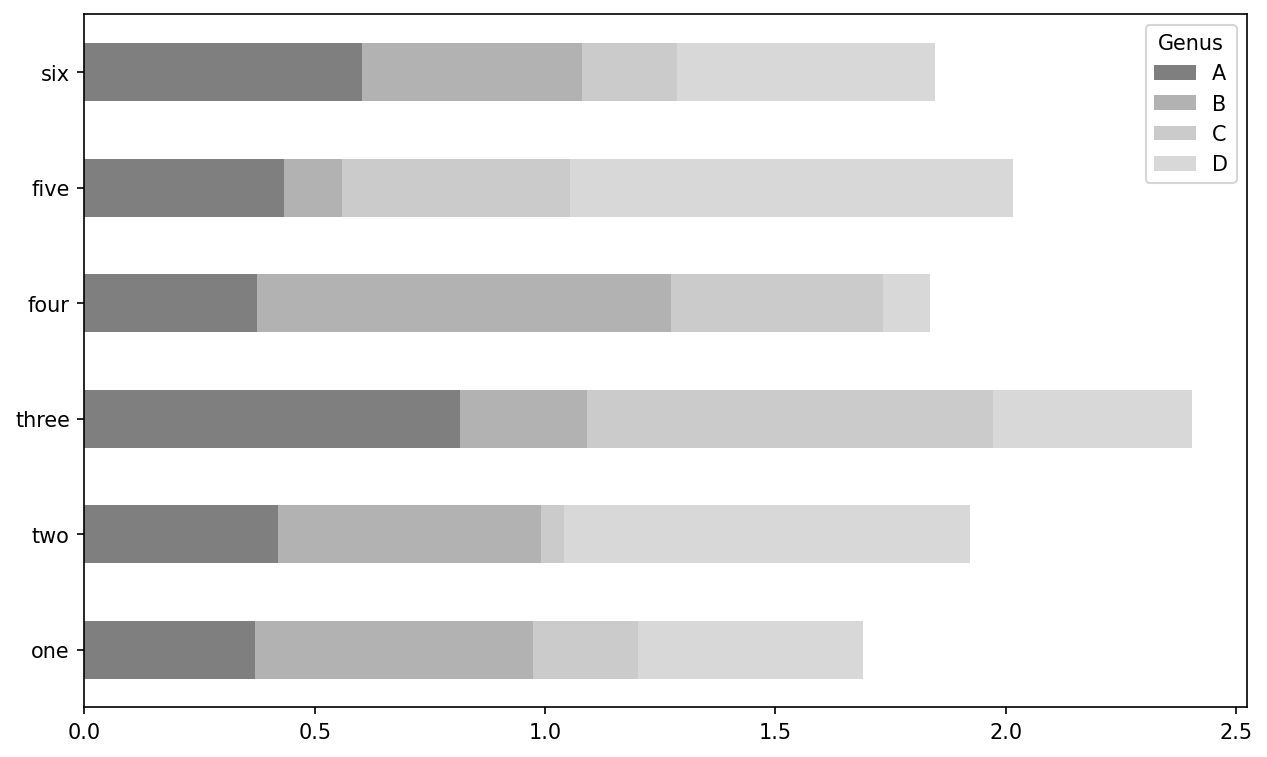

We create stacked bar plots from a DataFrame by passing stacked=True, resulting in the value in each row being stacked together horizontally (see DataFrame stacked bar plot):

In [75]: df.plot.barh(stacked=True, alpha=0.5)A useful recipe for bar plots is to visualize a Series’s value frequency using value_counts: s.value_counts().plot.bar().

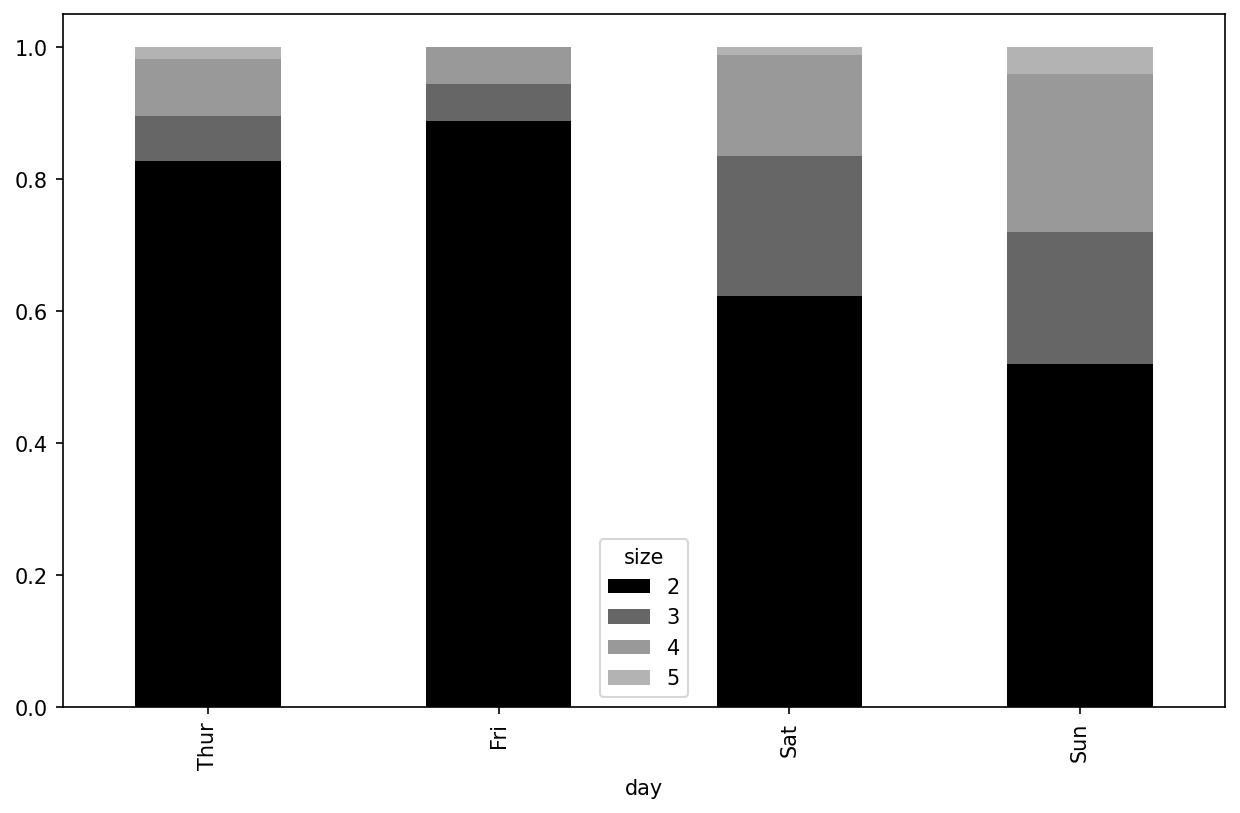

Let's have a look at an example dataset about restaurant tipping. Suppose we wanted to make a stacked bar plot showing the percentage of data points for each party size for each day. I load the data using read_csv and make a cross-tabulation by day and party size. The pandas.crosstab function is a convenient way to compute a simple frequency table from two DataFrame columns:

In [77]: tips = pd.read_csv("examples/tips.csv")

In [78]: tips.head()

Out[78]:

total_bill tip smoker day time size

0 16.99 1.01 No Sun Dinner 2

1 10.34 1.66 No Sun Dinner 3

2 21.01 3.50 No Sun Dinner 3

3 23.68 3.31 No Sun Dinner 2

4 24.59 3.61 No Sun Dinner 4

In [79]: party_counts = pd.crosstab(tips["day"], tips["size"])

In [80]: party_counts = party_counts.reindex(index=["Thur", "Fri", "Sat", "Sun"])

In [81]: party_counts

Out[81]:

size 1 2 3 4 5 6

day

Thur 1 48 4 5 1 3

Fri 1 16 1 1 0 0

Sat 2 53 18 13 1 0

Sun 0 39 15 18 3 1Since there are not many one- and six-person parties, I remove them here:

In [82]: party_counts = party_counts.loc[:, 2:5]Then, normalize so that each row sums to 1, and make the plot (see Fraction of parties by size within each day):

# Normalize to sum to 1

In [83]: party_pcts = party_counts.div(party_counts.sum(axis="columns"),

....: axis="index")

In [84]: party_pcts

Out[84]:

size 2 3 4 5

day

Thur 0.827586 0.068966 0.086207 0.017241

Fri 0.888889 0.055556 0.055556 0.000000

Sat 0.623529 0.211765 0.152941 0.011765

Sun 0.520000 0.200000 0.240000 0.040000

In [85]: party_pcts.plot.bar(stacked=True)So you can see that party sizes appear to increase on the weekend in this dataset.

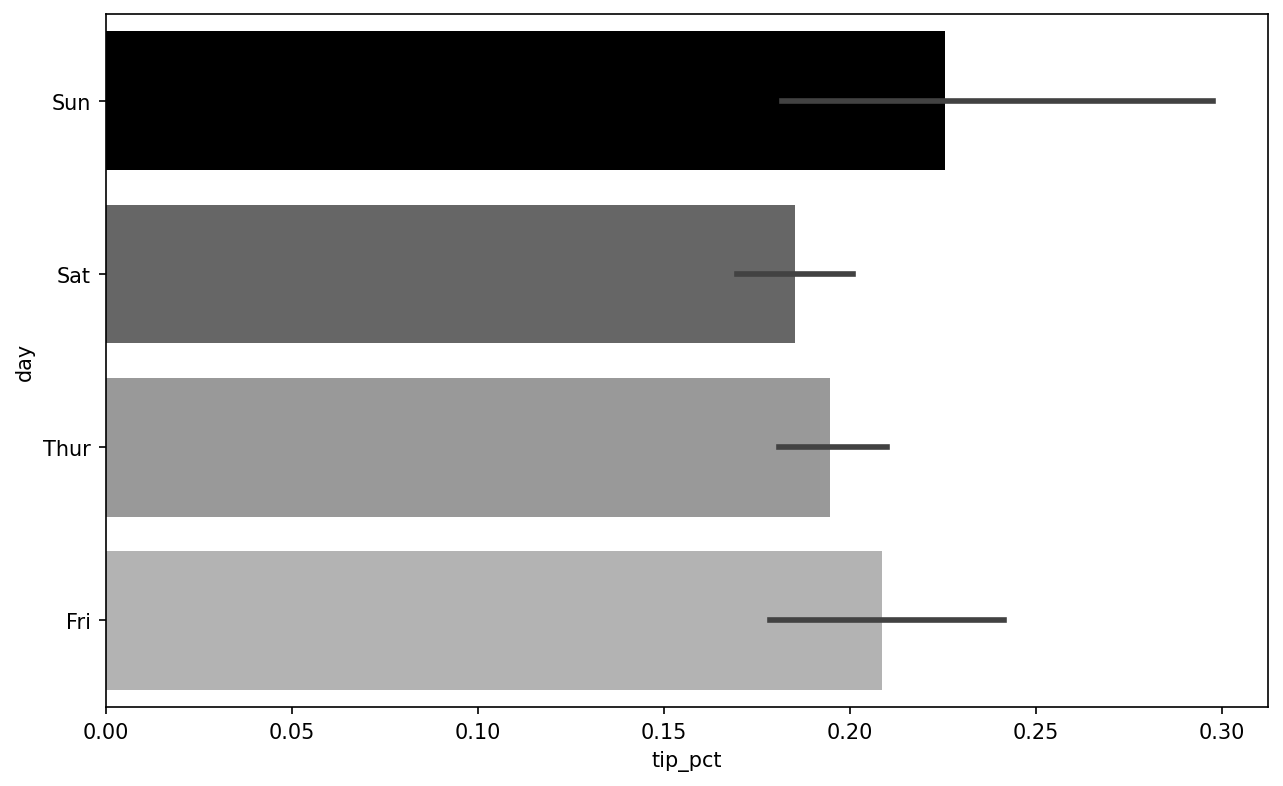

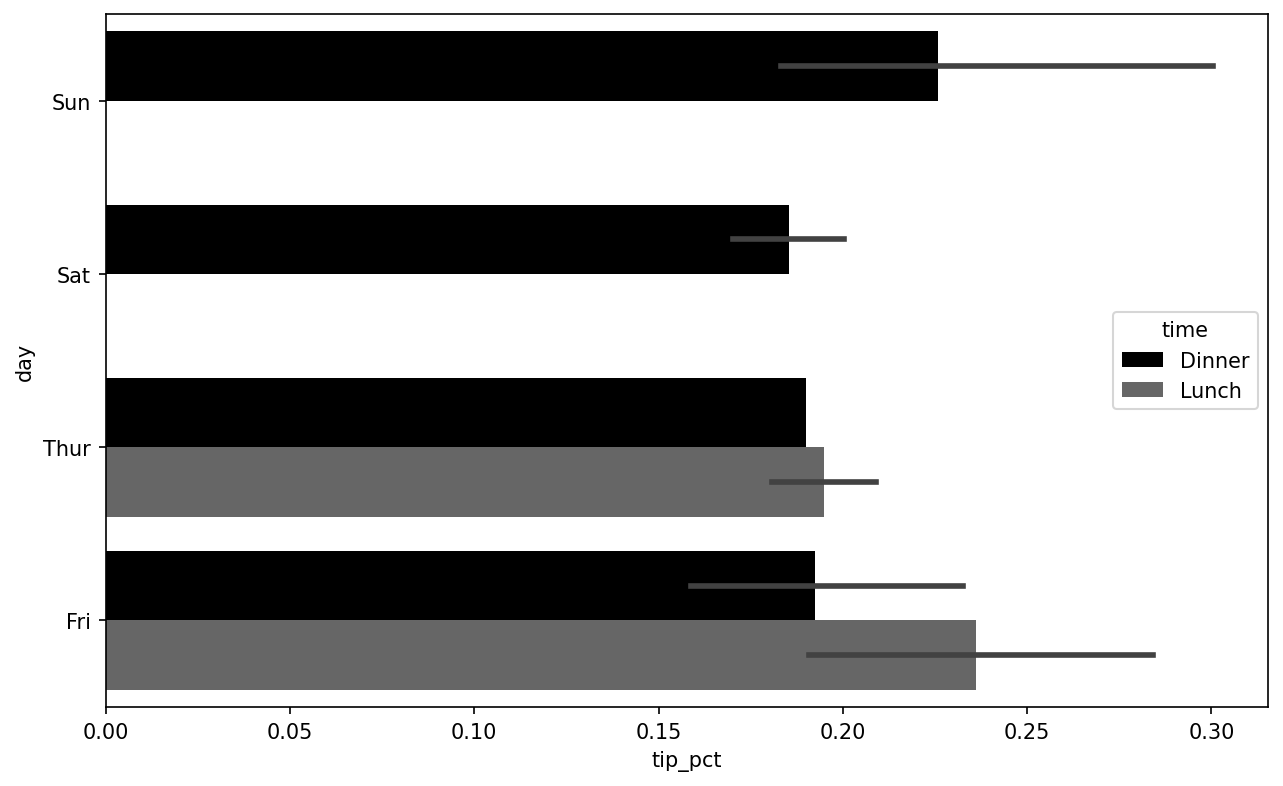

With data that requires aggregation or summarization before making a plot, using the seaborn package can make things much simpler (install it with conda install seaborn). Let's look now at the tipping percentage by day with seaborn (see Tipping percentage by day with error bars for the resulting plot):

In [87]: import seaborn as sns

In [88]: tips["tip_pct"] = tips["tip"] / (tips["total_bill"] - tips["tip"])

In [89]: tips.head()

Out[89]:

total_bill tip smoker day time size tip_pct

0 16.99 1.01 No Sun Dinner 2 0.063204

1 10.34 1.66 No Sun Dinner 3 0.191244

2 21.01 3.50 No Sun Dinner 3 0.199886

3 23.68 3.31 No Sun Dinner 2 0.162494

4 24.59 3.61 No Sun Dinner 4 0.172069

In [90]: sns.barplot(x="tip_pct", y="day", data=tips, orient="h")Plotting functions in seaborn take a data argument, which can be a pandas DataFrame. The other arguments refer to column names. Because there are multiple observations for each value in the day, the bars are the average value of tip_pct. The black lines drawn on the bars represent the 95% confidence interval (this can be configured through optional arguments).

seaborn.barplot has a hue option that enables us to split by an additional categorical value (see Tipping percentage by day and time):

In [92]: sns.barplot(x="tip_pct", y="day", hue="time", data=tips, orient="h")Notice that seaborn has automatically changed the aesthetics of plots: the default color palette, plot background, and grid line colors. You can switch between different plot appearances using seaborn.set_style:

In [94]: sns.set_style("whitegrid")When producing plots for black-and-white print medium, you may find it useful to set a greyscale color palette, like so:

sns.set_palette("Greys_r")Histograms and Density Plots

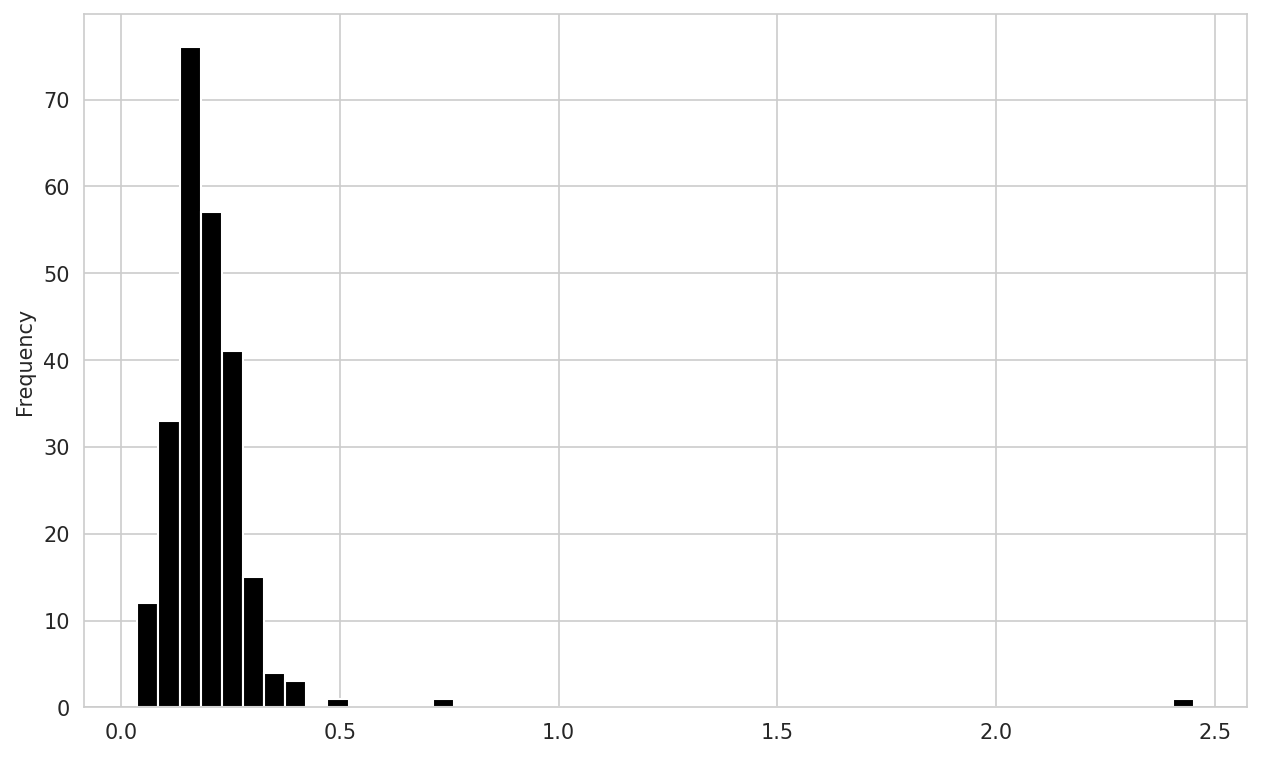

A histogram is a kind of bar plot that gives a discretized display of value frequency. The data points are split into discrete, evenly spaced bins, and the number of data points in each bin is plotted. Using the tipping data from before, we can make a histogram of tip percentages of the total bill using the plot.hist method on the Series (see Histogram of tip percentages):

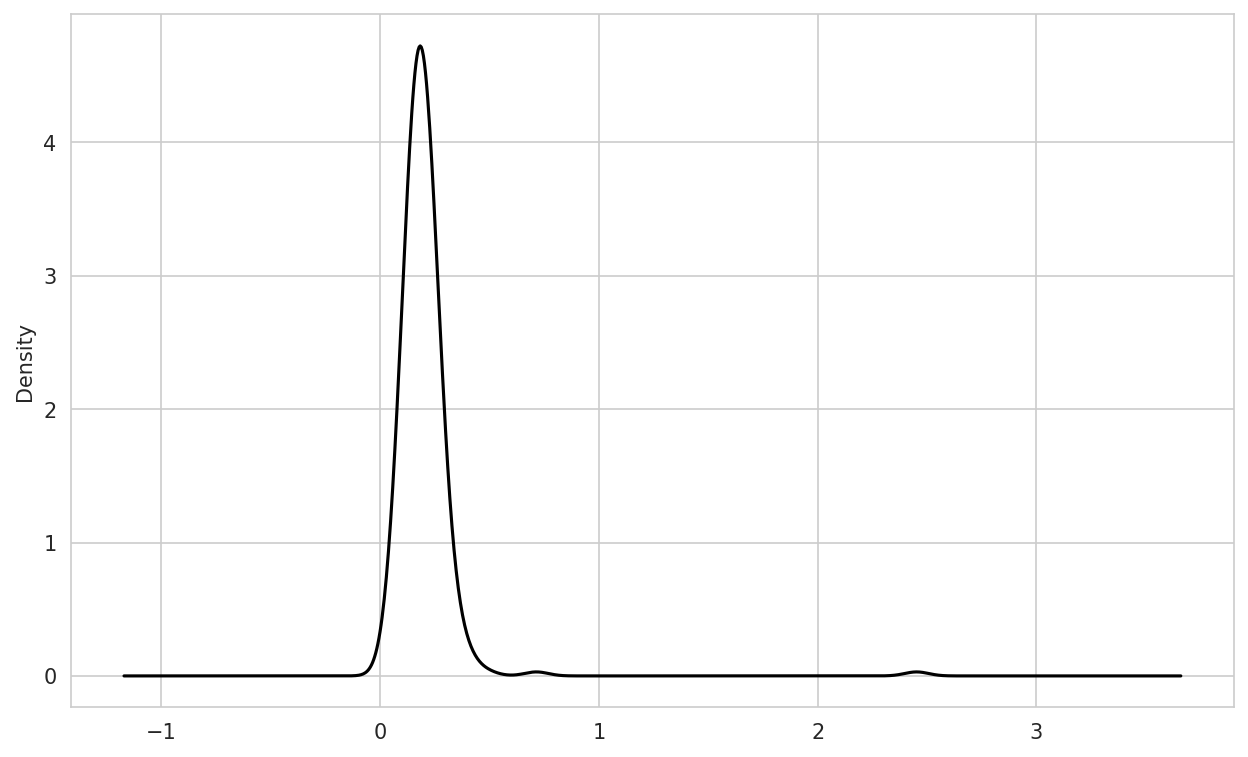

In [96]: tips["tip_pct"].plot.hist(bins=50)A related plot type is a density plot, which is formed by computing an estimate of a continuous probability distribution that might have generated the observed data. The usual procedure is to approximate this distribution as a mixture of "kernels"—that is, simpler distributions like the normal distribution. Thus, density plots are also known as kernel density estimate (KDE) plots. Using plot.density makes a density plot using the conventional mixture-of-normals estimate (see Density plot of tip percentages):

In [98]: tips["tip_pct"].plot.density()This kind of plot requires SciPy, so if you do not have it installed already, you can pause and do that now:

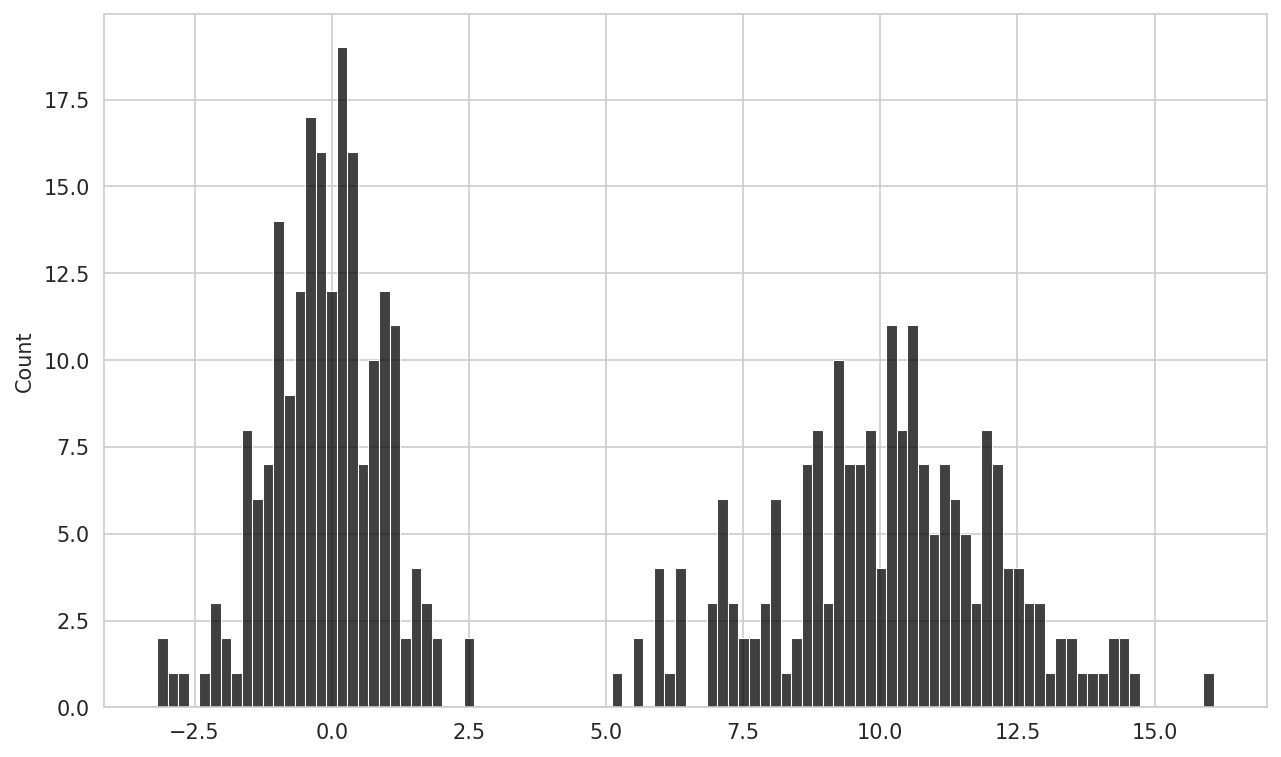

conda install scipyseaborn makes histograms and density plots even easier through its histplot method, which can plot both a histogram and a continuous density estimate simultaneously. As an example, consider a bimodal distribution consisting of draws from two different standard normal distributions (see Normalized histogram of normal mixture):

In [100]: comp1 = np.random.standard_normal(200)

In [101]: comp2 = 10 + 2 * np.random.standard_normal(200)

In [102]: values = pd.Series(np.concatenate([comp1, comp2]))

In [103]: sns.histplot(values, bins=100, color="black")Scatter or Point Plots

Point plots or scatter plots can be a useful way of examining the relationship between two one-dimensional data series. For example, here we load the macrodata dataset from the statsmodels project, select a few variables, then compute log differences:

In [104]: macro = pd.read_csv("examples/macrodata.csv")

In [105]: data = macro[["cpi", "m1", "tbilrate", "unemp"]]

In [106]: trans_data = np.log(data).diff().dropna()

In [107]: trans_data.tail()

Out[107]:

cpi m1 tbilrate unemp

198 -0.007904 0.045361 -0.396881 0.105361

199 -0.021979 0.066753 -2.277267 0.139762

200 0.002340 0.010286 0.606136 0.160343

201 0.008419 0.037461 -0.200671 0.127339

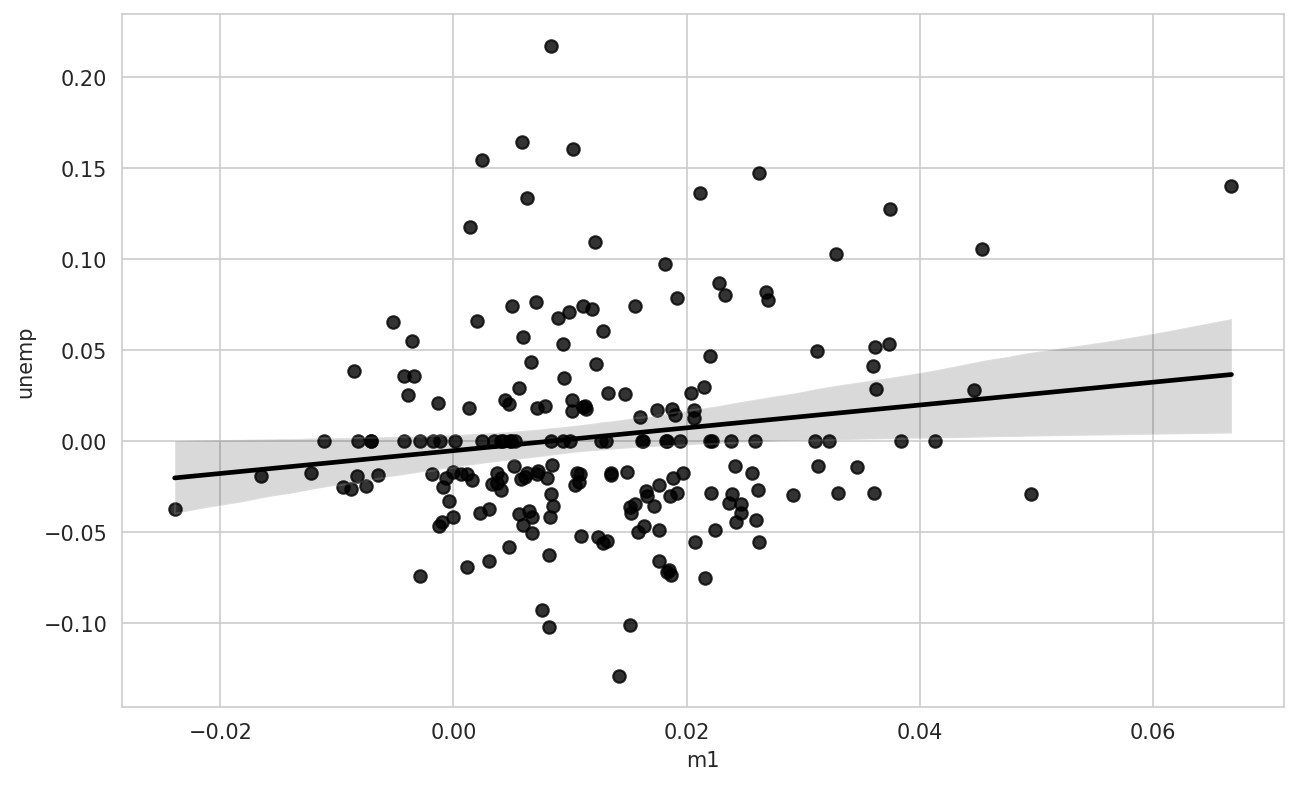

202 0.008894 0.012202 -0.405465 0.042560We can then use seaborn's regplot method, which makes a scatter plot and fits a linear regression line (see A seaborn regression/scatter plot):

In [109]: ax = sns.regplot(x="m1", y="unemp", data=trans_data)

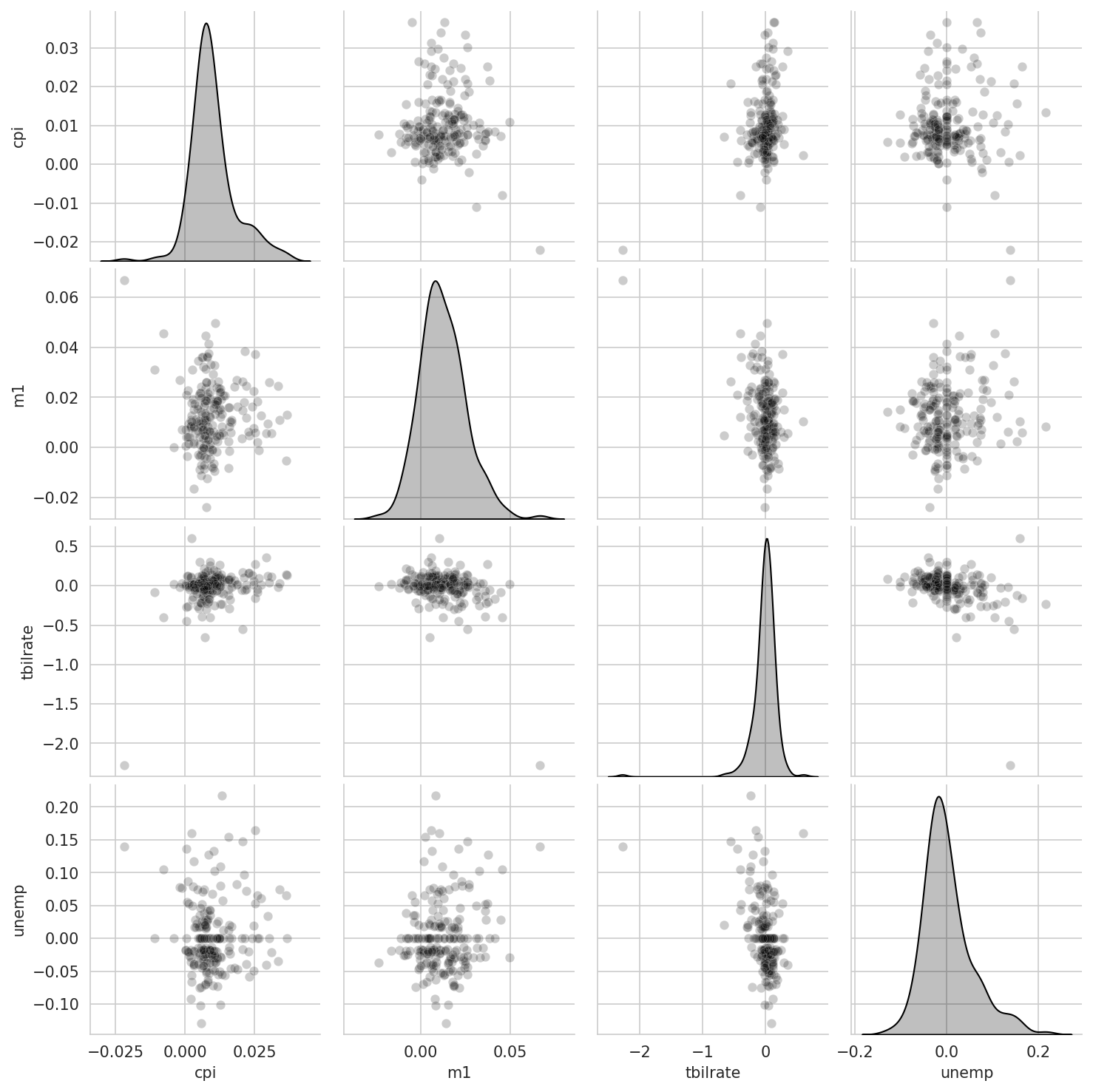

In [110]: ax.set_title("Changes in log(m1) versus log(unemp)")In exploratory data analysis, it’s helpful to be able to look at all the scatter plots among a group of variables; this is known as a pairs plot or scatter plot matrix. Making such a plot from scratch is a bit of work, so seaborn has a convenient pairplot function that supports placing histograms or density estimates of each variable along the diagonal (see Pair plot matrix of statsmodels macro data for the resulting plot):

In [111]: sns.pairplot(trans_data, diag_kind="kde", plot_kws={"alpha": 0.2})You may notice the plot_kws argument. This enables us to pass down configuration options to the individual plotting calls on the off-diagonal elements. Check out the seaborn.pairplot docstring for more granular configuration options.

Facet Grids and Categorical Data

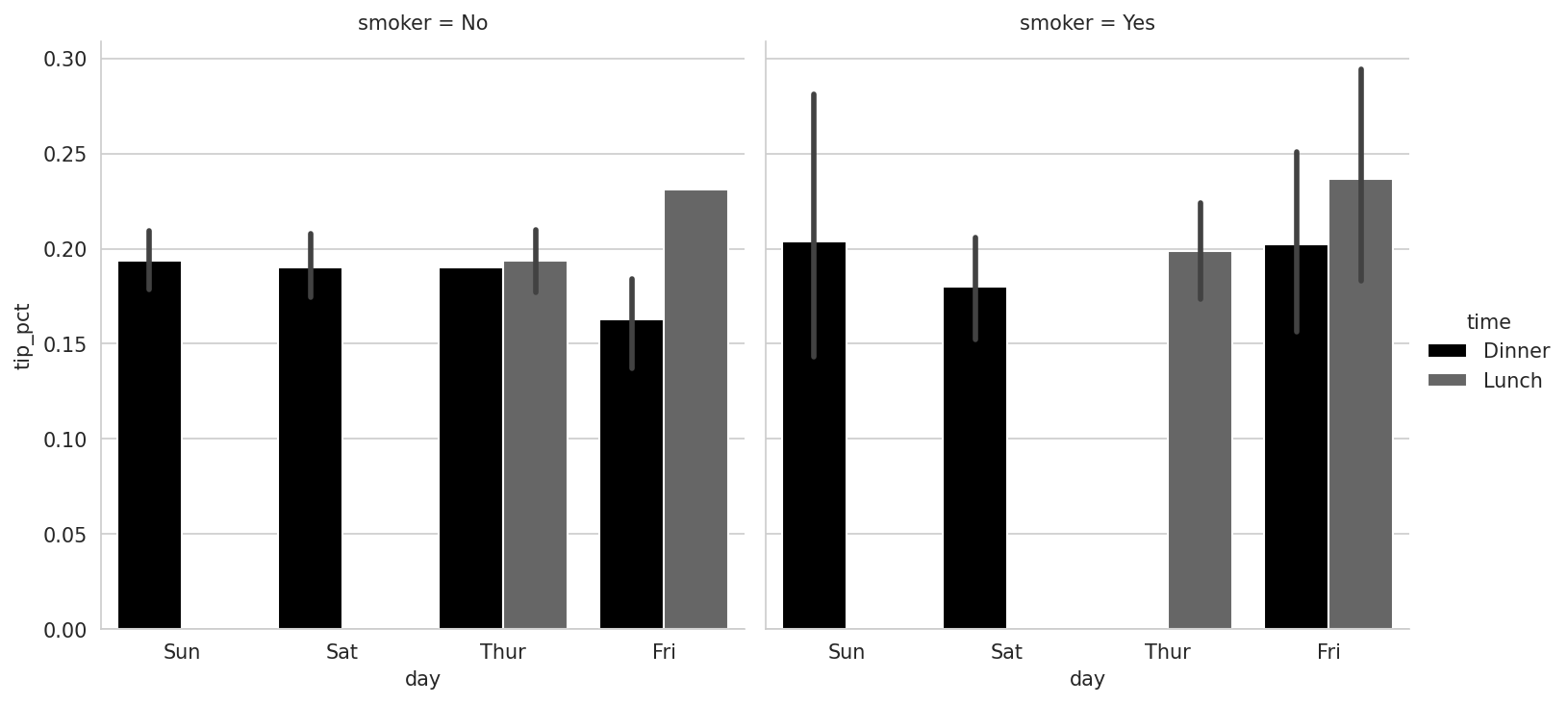

What about datasets where we have additional grouping dimensions? One way to visualize data with many categorical variables is to use a facet grid, which is a two-dimensional layout of plots where the data is split across the plots on each axis based on the distinct values of a certain variable. seaborn has a useful built-in function catplot that simplifies making many kinds of faceted plots split by categorical variables (see Tipping percentage by day/time/smoker for the resulting plot):

In [112]: sns.catplot(x="day", y="tip_pct", hue="time", col="smoker",

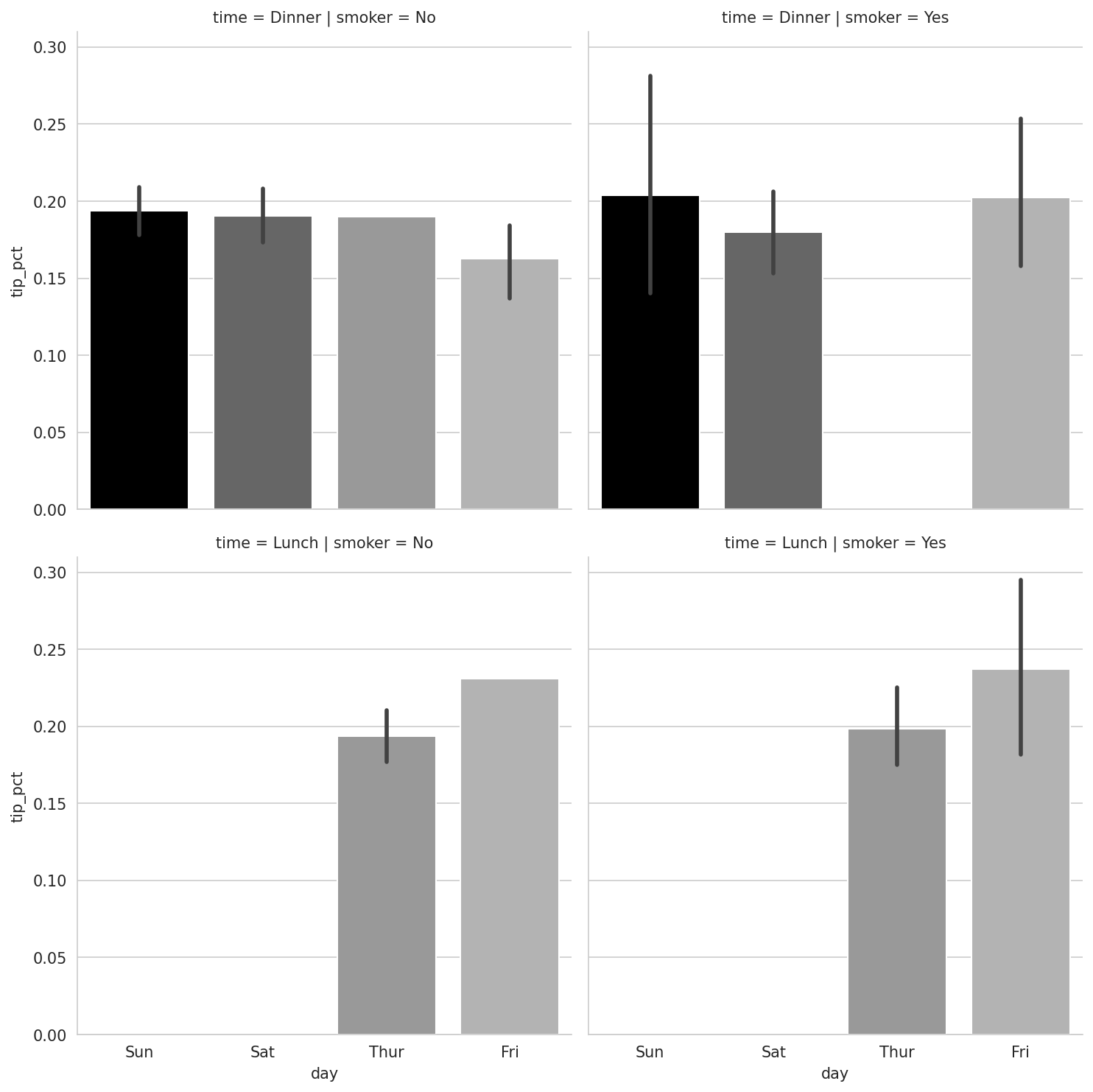

.....: kind="bar", data=tips[tips.tip_pct < 1])Instead of grouping by "time" by different bar colors within a facet, we can also expand the facet grid by adding one row per time value (see Tipping percentage by day split by time/smoker):

In [113]: sns.catplot(x="day", y="tip_pct", row="time",

.....: col="smoker",

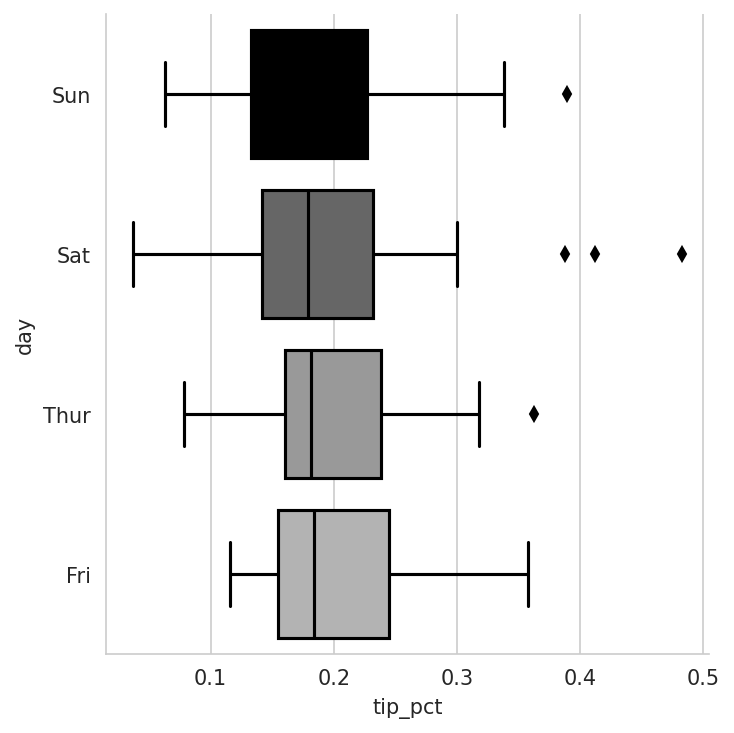

.....: kind="bar", data=tips[tips.tip_pct < 1])catplot supports other plot types that may be useful depending on what you are trying to display. For example, box plots (which show the median, quartiles, and outliers) can be an effective visualization type (see Box plot of tipping percentage by day):

In [114]: sns.catplot(x="tip_pct", y="day", kind="box",

.....: data=tips[tips.tip_pct < 0.5])You can create your own facet grid plots using the more general seaborn.FacetGrid class. See the seaborn documentation for more.

9.3 Other Python Visualization Tools

As is common with open source, there many options for creating graphics in Python (too many to list). Since 2010, much development effort has been focused on creating interactive graphics for publication on the web. With tools like Altair, Bokeh, and Plotly, it's now possible to specify dynamic, interactive graphics in Python that are intended for use with web browsers.

For creating static graphics for print or web, I recommend using matplotlib and libraries that build on matplotlib, like pandas and seaborn, for your needs. For other data visualization requirements, it may be useful to learn how to use one of the other available tools. I encourage you to explore the ecosystem as it continues to evolve and innovate into the future.

An excellent book on data visualization is Fundamentals of Data Visualization by Claus O. Wilke (O'Reilly), which is available in print or on Claus's website at https://clauswilke.com/dataviz.

9.4 Conclusion

The goal of this chapter was to get your feet wet with some basic data visualization using pandas, matplotlib, and seaborn. If visually communicating the results of data analysis is important in your work, I encourage you to seek out resources to learn more about effective data visualization. It is an active field of research, and you can practice with many excellent learning resources available online and in print.

In the next chapter, we turn our attention to data aggregation and group operations with pandas.